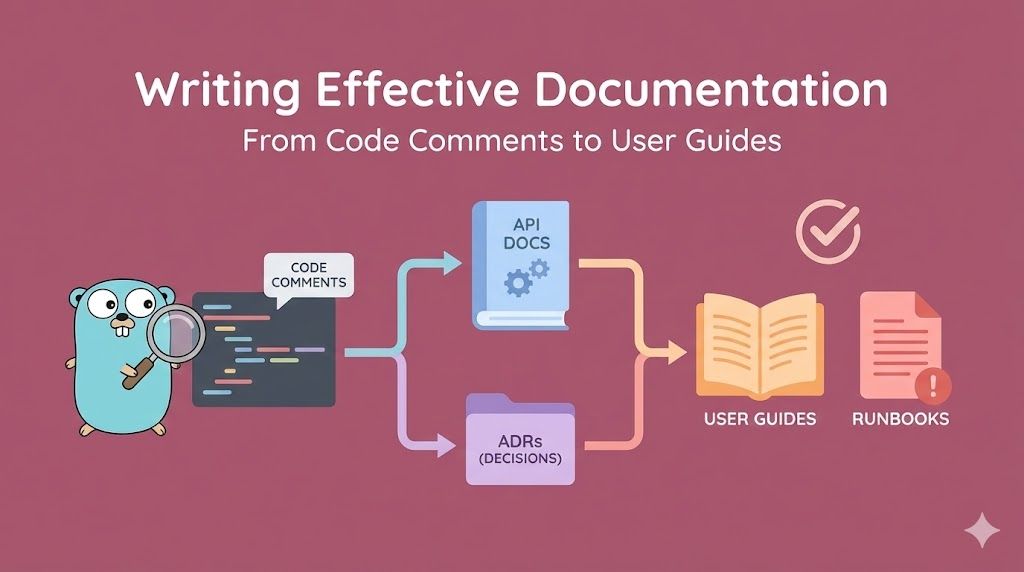

Writing Effective Documentation: From Code Comments to User Guides

A comprehensive guide to documentation that actually works. Master self-documenting code, API documentation, Architecture Decision Records (ADRs), and runbooks. Learn what developers actually need to understand and maintain systems, written from a senior engineer's perspective.

Writing Effective Documentation: From Code Comments to User Guides

The Complete Guide to Documentation That People Actually Read and Use

🎯 Introduction: Why Documentation Fails (And How to Fix It)

Let me start with a painful truth: Most documentation is useless.

Not because it’s hard to write. Not because writers aren’t skilled.

But because documentation is written for the writer’s future memory, not for the reader’s understanding.

The Problem: Documentation Theater

Organizations create documentation and think the job is done:

Manager: "We need documentation."

Team: "OK, we'll document everything."

[Team writes 50 pages of docs]

Manager: "Great, documentation done!"

Reality:

- No one reads the docs

- Docs become outdated immediately

- When someone needs help, they ask Slack instead

- Docs sit in repository, gathering digital dust

Why? Because documentation isn't about having documents.

It's about helping people understand and do things.What This Guide Is About

This is not a style guide. Not about grammar or formatting.

This is: How to write documentation that people actually use.

We will cover:

✅ Self-documenting code - Code so clear you barely need comments

✅ Code comments - When and how to write them (spoiler: rarely)

✅ API documentation - Making APIs intuitive and explainable

✅ Architecture Decision Records (ADRs) - Recording why decisions were made

✅ Runbooks - Step-by-step guides for operations

✅ User guides - Documentation for non-technical users

✅ README files - The entry point to your project

The perspective: What does someone new to this codebase actually need to know?

🏗️ Part 1: Self-Documenting Code - The Best Documentation is Code Itself

The highest form of documentation is code that explains itself.

If you need to write a comment to explain code, the code is probably unclear.

The Philosophy: Code Clarity Over Cleverness

Clever code (hard to read):

int calc(int x, int y) {

return (x ^ y) + ((x & y) << 1);

}

Clear code (easy to read):

int calculateSum(int firstNumber, int secondNumber) {

return firstNumber + secondNumber;

}

Intermediate (too clever):

int x = a << 1; // multiply by 2Developers admire clever code. But clever code is hard to understand.

The goal: Code that a junior developer reads and immediately understands.

Rule 1: Naming is Everything

The most powerful tool for self-documentation is meaningful names.

Variable Names

❌ Bad:

int d; // duration

string u; // user

bool f; // flag

✅ Good:

int durationInSeconds;

string userName;

bool isActive;Why?

Reason 1: Self-explanatory

- "durationInSeconds" - I immediately know what this is

- "d" - I need to search for context

Reason 2: Searchable

- Searching for "durationInSeconds" finds all uses

- Searching for "d" finds every letter in the file

Reason 3: Intention-revealing

- "isActive" suggests it's a boolean (true/false)

- "active" could be many things (noun, adjective, etc.)Function Names

❌ Bad:

function process(data) {

function handle(request, response) {

function doStuff() {

✅ Good:

function validateUserEmail(email) {

function extractUserIdFromRequest(request) {

function calculateMonthlyRevenue(transactions) {Why?

"process" - What does this do? I need to read the code.

"validateUserEmail" - I know exactly what it does without reading.

"handle" - Generic, could mean anything

"extractUserIdFromRequest" - Specific, clear intention

"doStuff" - Please no.Class/Type Names

❌ Bad:

class Manager

class Processor

class Util

✅ Good:

class UserAuthenticationManager

class PaymentProcessor

class DateUtilitiesSpecific names make code self-documenting.

Rule 2: Structure Code for Readability

How you organize code affects how understandable it is.

Group Related Functionality

❌ Bad (scattered logic):

class User {

constructor(name) { this.name = name; }

getAge() { ... }

validateEmail() { ... }

calculateBillingAmount() { ... }

isActive() { ... }

sendNotification() { ... }

getProfile() { ... }

}

User has 7 unrelated methods. Hard to understand at a glance.

✅ Good (grouped by concern):

class User {

constructor(name) { this.name = name; }

// Lifecycle methods

isActive() { ... }

getAge() { ... }

// Validation

validateEmail() { ... }

// Profile access

getProfile() { ... }

// Billing

calculateBillingAmount() { ... }

// Notifications

sendNotification() { ... }

}

Related methods grouped together. Much clearer.Keep Functions Small

❌ Bad (100 lines in one function):

function processPayment(order) {

// validate order

// calculate tax

// apply discounts

// process card

// send email

// update database

// log transaction

// handle errors

[... 100 lines ...]

}

You need to read all 100 lines to understand what happens.

✅ Good (small, focused functions):

function processPayment(order) {

validateOrder(order);

const total = calculateTotal(order);

processCard(order.card, total);

sendConfirmationEmail(order.customer);

updateInventory(order);

logTransaction(order, total);

}

Each line is a clear step. Easy to understand flow.The rule: If you need to scroll to see the entire function, it’s too big.

Rule 3: Use Types (When Available)

Static typing is documentation.

❌ JavaScript (unclear what parameters are):

function sendEmail(email, subject, body, includeAttachments) {

// ... what type is includeAttachments? boolean? string?

// ... what should email be? string? object?

}

✅ TypeScript (clear types):

function sendEmail(

email: string,

subject: string,

body: string,

includeAttachments: boolean

): Promise<void> {

// Types make it clear what's expected

}

Or with interfaces (more complex types):

interface EmailConfig {

recipient: string;

subject: string;

body: string;

attachments?: Attachment[];

priority: "normal" | "high" | "urgent";

}

function sendEmail(config: EmailConfig): Promise<void> {

// Much clearer than loose parameters

}Types serve as executable documentation. They’re checked by the compiler.

Rule 4: Handle Errors Explicitly

Error handling is documentation of what can go wrong.

❌ Bad (silent failure):

function getUserById(id) {

return users[id]; // What if id doesn't exist? Returns undefined silently.

}

✅ Good (explicit error):

function getUserById(id) {

const user = users[id];

if (!user) {

throw new Error(`User not found: id=${id}`);

}

return user;

}

The explicit error tells readers:

- This function can fail

- It fails when user doesn't exist

- The error message shows what went wrongRule 5: Avoid Magic Numbers and Strings

Magic numbers are unexplained constants.

❌ Bad:

if (user.age > 18 && user.score > 75 && user.accountDays > 365) {

// What are 18, 75, 365?

// What do they mean?

// Where did these numbers come from?

}

✅ Good:

const MINIMUM_AGE = 18;

const MINIMUM_CREDIT_SCORE = 75;

const MINIMUM_ACCOUNT_AGE_DAYS = 365;

if (user.age > MINIMUM_AGE &&

user.score > MINIMUM_CREDIT_SCORE &&

user.accountDays > MINIMUM_ACCOUNT_AGE_DAYS) {

// Immediately clear what these thresholds mean

}Named constants are self-documenting.

Rule 6: Reduce Complexity

Complex code requires explanation. Simple code doesn’t.

❌ Complex (needs explanation):

const result = obj.filter(x => x.p === 'active')

.map(x => x.a)

.reduce((acc, x) => acc + x.v, 0);

What does this do? You need to trace through it.

✅ Simple (clear intention):

const activeItems = obj.filter(x => x.status === 'active');

const amounts = activeItems.map(item => item.amount);

const total = amounts.reduce((sum, amount) => sum + amount, 0);

Or even clearer:

function calculateTotalActiveAmount(items) {

return items

.filter(item => item.status === 'active')

.map(item => item.amount)

.reduce((sum, amount) => sum + amount, 0);

}Clear is better than clever.

💬 Part 2: Code Comments - When to Write Them (Spoiler: Rarely)

Comments are often a code smell.

Not because comments are bad. But because if you need a comment, the code is probably unclear.

When NOT to Write Comments

Don’t Comment What Code Does (It’s Obvious)

❌ Bad comment (states the obvious):

// Add 5 to x

x = x + 5;

// Increment counter

counter++;

// Filter users where isActive is true

const activeUsers = users.filter(u => u.isActive);

The comment just restates what the code already says.

✅ Instead: Make the code clear

const adjustedValue = baseValue + DEFAULT_ADJUSTMENT;

counter++;

const activeUsers = users.filter(u => u.isActive);Don’t Comment Bad Code (Fix It Instead)

❌ Bad:

// This is a bit complex but it works

const x = arr.map(a => a.includes('x') ? a.split('x')[1] : null)

.filter(a => a)

.reduce((acc, a) => acc + a, '');

// Complex comment trying to explain complex code

✅ Good: Refactor to be clear

function extractValuesBetweenXDelimiters(items) {

return items

.map(item => splitOnDelimiter(item, 'x'))

.filter(value => value !== null)

.reduce((accumulated, value) => accumulated + value, '');

}

If code is confusing, refactor it. Don't comment it.Don’t Comment Implementation Details

❌ Bad:

// Check if length > 5

if (password.length > 5) {

The code already shows what's being checked.

✅ Better: Use a named constant and function

function isPasswordLongEnough(password) {

const MINIMUM_PASSWORD_LENGTH = 5;

return password.length > MINIMUM_PASSWORD_LENGTH;

}

if (isPasswordLongEnough(password)) {

No comment needed. The code is clear.When TO Write Comments

1. Explain the WHY (Not the WHAT)

❌ Bad (WHAT - obvious from code):

// Set flag to true

isProcessed = true;

✅ Good (WHY - not obvious from code):

// Mark as processed so we don't send duplicate notifications

// (See issue #456 for context on why duplicates were causing problems)

isProcessed = true;The code says WHAT. Comments should explain WHY.

2. Explain Non-Obvious Decisions

✅ Good comment (explains a non-obvious choice):

// We use `any` type here because the API returns inconsistent field names

// depending on the endpoint version. Type safety would require conditional types

// which adds complexity. Once we migrate to API v2, this can be properly typed.

const response: any = await fetchUserData();This explains WHY a normally-bad practice (using any) is acceptable here.

3. Warn About Dangers or Trade-offs

✅ Good comment (warns about danger):

// WARNING: This function must be called with exclusive lock on the database.

// Concurrent calls will cause race condition and data corruption.

// See synchronizeUserData() which handles locking correctly.

function unsafeSyncUserData(userId) {

// ...

}

This warning helps developers use the function correctly.4. Document Non-Obvious Algorithms

✅ Good comment (explains complex algorithm):

// This implements the Luhn algorithm for credit card validation.

// See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luhn_algorithm

// The algorithm:

// 1. Reverse the digits

// 2. Double every second digit

// 3. Sum all digits (for doubled digits, sum the two digits)

// 4. If total % 10 == 0, card is valid

function validateCreditCardNumber(cardNumber) {

// ... implementation ...

}This gives context and reference for an algorithm that isn’t self-documenting.

5. Note Temporary Hacks or Workarounds

✅ Good comment (documents temporary hack):

// HACK: Database returns null for empty strings due to legacy bug #789.

// Remove this check once database is fixed (estimated Q2 2026).

// Contact backend team before removing.

const actualValue = value === null ? '' : value;This tells future developers: this is temporary, here’s when to remove it, who to contact.

Comment Format: Make Them Useful

Bad Comments (Unhelpful)

❌ // TODO

❌ // FIXME

❌ // NOTE

❌ // HACK

These are vague. They don't help future readers.Good Comments (Helpful)

✅ // TODO: #456 Migrate to API v2 and remove any type (estimated 2 weeks)

✅ // FIXME: #789 Database returns null for empty strings, remove workaround after fix

✅ // NOTE: This must be synchronized with updateUserProfile() to avoid inconsistency

✅ // HACK: Temporary workaround for third-party library bug, upgrade to v3.0 when releasedInclude:

- Ticket number (traceable)

- Reason (understandable)

- Timeline (actionable)

The Comment Audit: How Many Is Too Many?

If comments are > 20% of code:

- Code is probably too complex

- Refactor instead of commenting more

If comments are < 5% of code:

- Probably healthy (code is clear)

- Only documenting important why's

Good ratio: 5-10% of code is comments

- Not over-commenting

- Not ignoring important context📚 Part 3: API Documentation - Making Endpoints Intuitive and Clear

An API without documentation is useless. An API with bad documentation is worse than useless.

Principle 1: Your API Documentation Should Be a Map

A good API doc answers these questions:

1. What is this API for? (High-level purpose)

2. How do I authenticate? (Security)

3. What endpoints exist? (Navigation)

4. What does each endpoint do? (Individual instructions)

5. What parameters does it accept? (Input)

6. What does it return? (Output)

7. What can go wrong? (Error handling)

8. Show me an example (Concrete example)Missing any of these = developers need to contact you for help.

Standard 1: OpenAPI/Swagger Specification

Modern API documentation uses OpenAPI (formerly Swagger).

Why? Because it’s:

- Machine-readable (can generate documentation automatically)

- Standard (understood by tools)

- Interactive (users can try endpoints directly)

Example OpenAPI spec:

openapi: 3.0.0

info:

title: User API

description: API for managing user accounts

version: 1.0.0

servers:

- url: https://api.example.com

description: Production server

paths:

/users:

get:

summary: Get list of users

description: Returns a paginated list of users

parameters:

- name: page

in: query

description: Page number (starts at 1)

schema:

type: integer

minimum: 1

default: 1

- name: limit

in: query

description: Number of results per page

schema:

type: integer

minimum: 1

maximum: 100

default: 20

responses:

"200":

description: Success

content:

application/json:

schema:

type: object

properties:

data:

type: array

items:

type: object

properties:

id:

type: string

name:

type: string

email:

type: string

pagination:

type: object

properties:

page:

type: integer

total:

type: integer

"400":

description: Invalid parameters

"401":

description: Unauthorized

"500":

description: Server error

post:

summary: Create a new user

requestBody:

required: true

content:

application/json:

schema:

type: object

properties:

name:

type: string

email:

type: string

format: email

required:

- name

- email

responses:

"201":

description: User created

content:

application/json:

schema:

type: object

properties:

id:

type: string

name:

type: string

email:

type: string

"400":

description: Invalid input

"409":

description: Email already existsThis specification:

✅ Defines every endpoint

✅ Lists all parameters

✅ Shows all possible responses

✅ Includes error cases

✅ Has examples for each

Tools like Swagger UI automatically generate interactive documentation from this.

Principle 2: Every Endpoint Needs These Details

For each API endpoint, document:

1. Purpose (One Line)

✅ "Get user by ID"

❌ "User endpoint"2. Description (One Paragraph)

✅ "Returns a single user's profile including name, email, and account status.

Does not return sensitive fields like password hash or API keys."

❌ "Gets the user"3. Authentication Required?

✅ "Requires Bearer token in Authorization header"

❌ No mention of auth4. Parameters

✅ List each parameter with:

- Name: userId

- Type: string (UUID format)

- Description: "The unique identifier of the user"

- Required: yes

- Example: "550e8400-e29b-41d4-a716-446655440000"

❌ "Pass user id"5. Request Example

✅

GET /users/550e8400-e29b-41d4-a716-446655440000

Authorization: Bearer eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIs...

❌ No example shown6. Response Example

✅

{

"id": "550e8400-e29b-41d4-a716-446655440000",

"name": "Alice Johnson",

"email": "alice@example.com",

"status": "active",

"createdAt": "2024-01-15T10:30:00Z"

}

❌ "Returns user object"7. Error Cases

✅

400 Bad Request: Invalid userId format

401 Unauthorized: Missing or invalid authentication token

404 Not Found: User with given ID does not exist

500 Internal Server Error: Database connection failed

❌ "May return errors"Principle 3: Group Endpoints by Resource

/users

GET /users - List all users

POST /users - Create user

GET /users/{id} - Get specific user

PUT /users/{id} - Update user

DELETE /users/{id} - Delete user

/users/{id}/profile

GET /users/{id}/profile - Get profile

PUT /users/{id}/profile - Update profile

/users/{id}/settings

GET /users/{id}/settings - Get settings

PUT /users/{id}/settings - Update settings

Grouping makes it clear what belongs together.Principle 4: Document Common Patterns

Don’t document the same thing over and over:

Instead of documenting authentication in every endpoint:

Write ONCE in a section called "Authentication":

"All endpoints require a Bearer token in the Authorization header.

Tokens are obtained by calling POST /auth/token.

Tokens expire after 1 hour."

Then reference it: "See Authentication section for details."Principle 5: Provide Working Examples

Documentation is useless without examples developers can run:

❌ Bad:

"Pass the user ID in the URL and call the endpoint."

✅ Good:

cURL:

curl -H "Authorization: Bearer YOUR_TOKEN" \

https://api.example.com/users/550e8400-e29b-41d4-a716-446655440000

JavaScript:

const response = await fetch(

'https://api.example.com/users/550e8400-e29b-41d4-a716-446655440000',

{

headers: {

'Authorization': `Bearer ${token}`

}

}

);

const user = await response.json();

Python:

import requests

headers = {'Authorization': f'Bearer {token}'}

response = requests.get(

'https://api.example.com/users/550e8400-e29b-41d4-a716-446655440000',

headers=headers

)

user = response.json()Examples in multiple languages help everyone.

🏛️ Part 4: Architecture Decision Records (ADRs) - Documenting the Why

An ADR is a record of an important decision and why it was made.

Not just WHAT you decided, but WHY. This is crucial.

Why ADRs Matter

Current state (no ADRs):

Codebase uses PostgreSQL for everything.

New developer asks: "Why PostgreSQL? Why not MongoDB?"

Senior developer responds: "Good question. I think it was because...

Actually, I don't remember. Whoever decided this isn't here anymore."

Months later, another developer suggests switching to MongoDB.

Everyone spends 2 weeks evaluating.

Discovers the original reason was "relational data structure."

Could have saved 2 weeks with documentation.

---

With ADRs:

Codebase uses PostgreSQL for everything.

New developer asks: "Why PostgreSQL?"

Points to ADR-003: "Database Selection Decision"

Reads: "We chose PostgreSQL because our data is highly relational.

Customer records link to orders, which link to items, which link to reviews.

PostgreSQL handles these relationships efficiently.

MongoDB was considered but rejected because it would require duplicating

customer data across multiple collections, leading to inconsistency issues.

Cost: PostgreSQL $500/month vs MongoDB $400/month, difference acceptable."

Developer now understands: Don't suggest MongoDB, the tradeoff was already considered.ADR Format

A standard ADR has these sections:

1. Title

ADR-001: Database Selection for Core Application

Simple, clear title starting with ADR number.2. Status

Proposed | Accepted | Superseded | Deprecated

Proposed: Still deciding

Accepted: Decided and in use

Superseded: We made a different decision later (ADR-025 supersedes this)

Deprecated: No longer relevant but kept for history3. Context

Explain the problem and situation:

Our application needs to store customer data, orders, and transactions.

Data structure is highly relational.

We need to store 10M+ records with complex queries.

Current system uses flat files, no longer scales.4. Decision

State clearly what was decided:

We will use PostgreSQL as our primary database.

We will use Redis for caching frequently accessed data.

We will not use a NoSQL database for primary storage.5. Rationale

Explain WHY this decision was made:

PostgreSQL was chosen because:

1. Relational Structure: Our data has complex relationships

(customers → orders → items → reviews).

PostgreSQL handles these relationships efficiently.

MongoDB would require denormalizing data (duplicating records),

leading to inconsistency issues.

2. ACID Transactions: Financial data must be consistent.

PostgreSQL guarantees ACID compliance.

MongoDB doesn't guarantee consistency across multiple documents.

3. Cost: PostgreSQL managed service = $500/month.

MongoDB = $400/month.

Additional $100/month acceptable for consistency guarantee.

4. Querying: Complex reports require complex joins.

PostgreSQL optimizes for joins.

MongoDB slow for complex queries across documents.

5. Ecosystem: Team experienced with PostgreSQL.

Learning curve for MongoDB would add 2-3 months.

Alternatives Considered:

- DynamoDB: No, too expensive for scale needed (~$2000/month)

- MySQL: Works, but PostgreSQL has better performance on our workload

- Cassandra: Over-engineered, too complex for our needs

- MongoDB: See rationale above

Consequences:

- Positive: Consistent, reliable, team familiar

- Negative: Scaling to extreme scale requires sharding (complex)6. Consequences

What are the implications?

Positive:

- Consistent data (ACID transactions)

- Team knows the technology

- Cost-effective

- Good performance for queries we need

Negative:

- If we exceed 10M records, sharding becomes necessary (complex)

- Vertical scaling more limited than MongoDB

- PostgreSQL expertise required for optimization

Neutral:

- Different backup strategy than previous system

- Requires DBA for large scale (we'll hire)7. Alternatives Considered

Show you thought this through:

Option A: MongoDB

- Pro: Flexible schema, easier for unstructured data

- Con: No ACID guarantees, requires denormalization

- Con: Slower on complex queries

- Rejected because: Data is highly relational, ACID needed

Option B: DynamoDB

- Pro: Fully managed, unlimited scale

- Con: Limited query capability ($2000+/month cost)

- Rejected because: Over-engineered, too expensive

Option C: Cassandra

- Pro: Horizontal scalability

- Con: Complex, requires expertise, overkill for our needs

- Rejected because: We don't need Cassandra's level of scale yet8. References

Link to related decisions or documentation:

Related:

- ADR-002: Caching Strategy (decided we'd use Redis)

- ADR-004: Database Backup Strategy

- Document: Database Performance Analysis (why PostgreSQL is faster)Complete ADR Example

# ADR-003: Payment Processing Service - Stripe vs PayPal vs Square

**Status:** Accepted

**Context:**

We need to process credit card payments for our SaaS platform.

Currently using manual payment entry (not scalable).

Expect 1000+ transactions/month within 6 months.

Need PCI compliance without managing sensitive data ourselves.

**Decision:**

We will use Stripe as our payment processor.

We will use Stripe's hosted checkout (reduces PCI scope).

We will store only Stripe token IDs, never raw card data.

**Rationale:**

1. Integration: Stripe has excellent documentation and SDKs.

Setup takes days, not weeks.

2. Security: Stripe handles PCI compliance.

We never touch raw card data.

Reduces our liability significantly.

3. Features: Stripe supports recurring billing, invoicing, and disputes.

All in one platform (don't need multiple services).

4. Reliability: 99.99% uptime SLA.

Stripe-to-bank settlement is fast (2 business days).

5. Cost: 2.9% + $0.30 per transaction.

At 1000 transactions/month avg $100 = $2900 in fees.

PayPal: 2.2% + $0.30 = $2300 (cheaper but worse ecosystem).

Square: 2.9% + $0.30 = same as Stripe.

6. Ecosystem: Stripe integrates with 100+ platforms.

If we ever use accounting software (FreshBooks), it connects to Stripe.

**Consequences:**

Positive:

- No PCI compliance burden

- Security done right from start

- Webhook system for payment status updates

- Good dashboard for tracking transactions

Negative:

- Platform lock-in (switching later is effort)

- Cost increases as transaction volume grows

- Stripe controls pricing (could increase fees)

**Alternatives Considered:**

Option A: PayPal

- Pro: Slightly cheaper (2.2% vs 2.9%)

- Con: Worse developer experience

- Con: Reputation issues (slower support)

- Rejected: Better long-term to use Stripe

Option B: Square

- Pro: Same cost and features as Stripe

- Con: Smaller ecosystem

- Con: Less developer-friendly

- Rejected: Stripe is more developer-friendly

Option C: Build ourselves

- Pro: No fees, complete control

- Con: PCI compliance nightmare ($$$)

- Con: 6 months of development

- Con: Ongoing security burden

- Rejected: Too risky, too expensive

**References:**

- https://stripe.com/docs

- Stripe vs PayPal comparison: [internal document]

- ADR-001: API Architecture (related)When to Write an ADR

Write an ADR when you’re deciding:

✅ Technology selection (database, framework, library)

✅ Architecture pattern (monolith vs microservices)

✅ Deployment strategy

✅ Security approach

✅ API design

✅ Major process changes

❌ Routine implementation details

❌ Variable naming (covered in code comments)

❌ Method organization (covered in code structure)Storing ADRs

ADRs should be:

Location: In the repository (not in Confluence or Google Docs)

Why: Version control, tracked with code, reviewed like code

Organization:

docs/adr/

ADR-001-database-selection.md

ADR-002-caching-strategy.md

ADR-003-payment-processor.md

README.md (index of all ADRs)

README.md contents:

# Architecture Decision Records

| ADR | Title | Status |

|-----|-------|--------|

| ADR-001 | Database Selection | Accepted |

| ADR-002 | Caching Strategy | Accepted |

| ADR-003 | Payment Processor | Accepted |

| ADR-004 | API Authentication | Proposed |🔧 Part 5: Runbooks - Step-by-Step Guides for Operations

A runbook is an operational manual. Step-by-step instructions for how to do something.

Runbooks are for:

- How to deploy

- How to debug production issues

- How to handle emergencies

- How to backup/restore

- How to scale up

- How to perform maintenance

Runbook Format

1. Title and Purpose

# Runbook: Deploy to Production

Purpose: Deploy the application to production environment

Audience: Deployment engineers, DevOps team

Frequency: Multiple times per day (as needed)

Emergency?: No (this is planned deployment)2. Prerequisites

What needs to be true before you start:

Prerequisites:

- You have AWS credentials with deployment permissions

- You have CLI tools installed: docker, kubectl, aws-cli

- The application has passed all CI/CD checks

- You have the deployment checklist (below)

- You have notified the team on Slack: #deployments3. Steps (Numbered, Clear)

Each step should be actionable (not require interpretation):

❌ Bad (unclear):

1. Deploy the app

2. Make sure it works

3. Rollback if needed

✅ Good (actionable):

1. Pull the latest code from main branch

Command: git checkout main && git pull origin main

2. Verify tests pass locally

Command: npm test

Expected: "All tests passed" message

If tests fail: Stop, investigate, fix before continuing

3. Build Docker image

Command: docker build -t app:latest .

Expected: Docker image created without errors

If fails: Check Dockerfile, run docker logs

4. Push Docker image to registry

Command: docker push 123456789.dkr.ecr.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/app:latest

Expected: Image appears in ECR console

If fails: Check AWS credentials with: aws sts get-caller-identity

5. Deploy to Kubernetes

Command: kubectl apply -f deployment.yaml --namespace=production

Expected: New pods starting, old pods terminating gracefully

If fails: Check with: kubectl describe deployment app

6. Wait for all replicas to be ready

Command: kubectl get deployment app --namespace=production --watch

Wait for: READY column shows 3/3

Timeout: If not ready after 5 minutes, investigate

Command: kubectl describe pod -n production -l app=app

7. Health check

Command: curl https://api.example.com/health

Expected: Returns {"status":"healthy"} with 200 status code

If unhealthy: Check logs with: kubectl logs -l app=app --namespace=production

8. Smoke test critical user flow

- Navigate to https://app.example.com in browser

- Login with test account (user: test@example.com, password: in 1Password)

- Create a test item

- Verify it appears in list

- If any step fails: Proceed to Rollback section

9. Announce deployment completion

Post in Slack #deployments channel: "Deployed commit <hash> to production"4. Verification Steps

How do you know it worked?

Verification:

☐ Application is responding to requests

☐ No increased error rate (check DataDog dashboard)

☐ No increased latency (check New Relic dashboard)

☐ Critical business flow works (users can login, create orders, etc.)

☐ No customer complaints in support (check Zendesk)

☐ Logs are clean (no unexpected errors)5. Rollback Procedure

What to do if something goes wrong:

Rollback (Emergency Only):

1. Announce rollback in Slack

Message: "@here Rolling back due to <reason>"

2. Revert to previous version

Command: kubectl set image deployment/app \

app=123456789.dkr.ecr.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/app:v1.2.3 \

--namespace=production

3. Wait for pods to restart

Command: kubectl get deployment app --namespace=production --watch

Wait for: All pods running again (should take 30-60 seconds)

4. Health check after rollback

Command: curl https://api.example.com/health

Expected: {"status":"healthy"} with 200 code

5. Verify old version works

- Test critical user flow again

- If passes: rollback successful

6. Post-mortem (within 24 hours)

- What went wrong?

- Why didn't we catch it in testing?

- How do we prevent next time?

- Document in: docs/incidents/2026-01-10-deployment-failure.md6. Emergency Contacts

Who to contact if something goes wrong:

If you need help:

- Deployment issues: @devops-team on Slack

- Application errors: @backend-team on Slack

- Database issues: @database-team (on-call: check PagerDuty)

- Network issues: @platform-team on Slack

On-call rotation:

- Check PagerDuty escalation policy

- Don't guess, contact the right personCommon Runbooks Every Team Needs

1. Deployment Runbook

- How to deploy to each environment

- Rollback procedure

2. Incident Response Runbook

- System is down, what do you do?

- How to investigate

- Who to notify

- Escalation path

3. Database Maintenance Runbook

- How to backup

- How to restore from backup

- How to run migrations

- How to check database health

4. Scaling Runbook

- How to scale up when traffic increases

- How to scale down when traffic decreases

- How to detect when scaling is needed

5. Security Incident Runbook

- Suspected breach, what do you do?

- How to isolate system

- How to investigate

- How to notify users

6. Third-party Integration Failures

- Payment processor down, what do you do?

- Email service down, what do you do?

- For each external dependency, have a runbook

7. User Data Requests

- GDPR request: export user data

- GDPR request: delete user data

- Steps to fulfill each requestRunbook Best Practices

1. Test Runbooks Regularly

Untested runbooks are useless:

- They have typos

- Commands don't work

- They're out of date

Monthly: Pick a runbook

Run through all steps exactly as written

If anything is wrong, fix it

Mark as "tested on [date]" at top of document2. Keep Runbooks in the Repository

❌ Word document on someone's laptop (lost if they leave)

❌ Google Doc that gets deleted (permission issues)

❌ Internal wiki that goes offline (not accessible during emergency)

✅ Markdown in git repository (versioned, backed up)

✅ Accessible 24/7

✅ Everyone has access3. Version Runbooks

At top of each runbook:

# Runbook: Deploy to Production

Version: 2.3

Last updated: 2026-01-10 by Alice

Last tested: 2026-01-09

Next review: 2026-02-10

This way you know if the runbook is current.📖 Part 6: README Files - Your Project’s First Impression

A README is the entry point to your project.

A good README answers: “What is this and how do I use it?”

Essential README Sections

1. Project Title and One-Line Description

# Payment Processing Service

Fast, reliable payment processing for SaaS applications.Not:

# Project Repo2. Quick Start (Get Running in 5 Minutes)

## Quick Start

### Installation

```bash

git clone https://github.com/company/payment-service.git

cd payment-service

npm installConfiguration

Copy the example config:

cp .env.example .envRun

npm run startApplication starts on http://localhost:3000

Test

npm test

Someone should be able to clone and run in 5 minutes.

#### 3. Project Structure

Project Structure

src/

api/ - REST API endpoints

services/ - Business logic

models/ - Data models

utils/ - Utility functions

middleware/ - Express middleware

tests/ - Test files

docs/

API.md - API documentation

ARCHITECTURE.md - System architecture

adr/ - Architecture decisions

scripts/

migrate.sh - Database migrations

deploy.sh - Deployment script4. Features

## Features

✅ Process credit cards securely (PCI-DSS compliant)

✅ Support recurring billing

✅ Handle disputes and chargebacks

✅ Webhook notifications for payment status

✅ Admin dashboard for transaction management

✅ API rate limiting (1000 req/min)

✅ 99.9% uptime SLA5. API Overview

## API Overview

### Create Payment

```bash

POST /api/payments

{

"amount": 1000,

"currency": "USD",

"cardToken": "tok_visa",

"description": "Monthly subscription"

}

Response:

{

"id": "pay_123",

"status": "succeeded",

"amount": 1000

}Link to full API docs: Full API Documentation

#### 6. Configuration

Configuration

Create .env file:

DATABASE_URL=postgresql://user:password@localhost/db

STRIPE_API_KEY=sk_test_123...

LOG_LEVEL=info

PORT=3000

NODE_ENV=developmentSee Configuration Guide for all options.

#### 7. Development

Development

Prerequisites

- Node.js 18+

- PostgreSQL 13+

- Docker (for running PostgreSQL locally)

Setup

npm install

npm run migrate # Run database migrations

npm run seed # Seed test data

npm run start:dev # Start with auto-reloadRunning Tests

npm test # Run all tests

npm run test:watch # Watch for changes

npm run test:coverage # Generate coverage reportCode Quality

npm run lint # Run linter

npm run format # Format code

npm run type-check # TypeScript checkingSee Development Guide for detailed instructions.

#### 8. Deployment

Deployment

Production

npm run build

npm run deploy:prodStaging

npm run deploy:stagingSee Deployment Guide for manual steps and rollback procedures.

#### 9. Contributing

Contributing

We welcome contributions!

- Fork the repository

- Create a feature branch:

git checkout -b feature/your-feature - Follow Code Standards

- Write tests for new functionality

- Submit a pull request

See CONTRIBUTING.md for detailed guidelines.

#### 10. License and Contact

License

MIT License - see LICENSE file

Contact and Support

- Issues: GitHub Issues

- Questions: Email support@company.com

- Slack: #payment-service on company workspace

- On-call: Check PagerDuty for escalation

### README Anti-Patterns

❌ “This is a payment service” (not descriptive enough) ✅ “Payment processing for SaaS: PCI-compliant, recurring billing, webhook support”

❌ “Clone and run” (no actual instructions) ✅ “git clone … && npm install && npm start”

❌ “See documentation for details” (documentation doesn’t exist) ✅ Link to actual documentation files

❌ 50 pages of detail (too long, no one reads) ✅ Quick start (5 min) + links to detailed guides

❌ Outdated (last updated 2023) ✅ “Last updated 2026-01-10 by Alice”

---

## 🎯 Conclusion: The Documentation Philosophy

Let me tie this together with a unified philosophy:

### The Principle: Documentation is for Readers, Not Writers

Bad philosophy: “I’m documenting this so I remember it later.”

Good philosophy: “I’m documenting this so someone else (or future me) can understand and use it without asking me questions.”

This changes everything.

### The Hierarchy of Documentation

Best: Code so clear it needs no explanation Good: Code + minimal comments explaining why OK: Code + comments + external documentation Bad: Unclear code + lots of comments trying to explain it Worst: No documentation at all

Strive for the top.

### Documentation Maintenance

Documentation rots. It becomes outdated.

Rule: If code changes, documentation must change. Not: “I’ll update docs later” But: Include doc updates in PR/commit.

Setup: Automated checks

- Broken links in documentation (automated check)

- Outdated examples (manual review in PRs)

- Missing API documentation (check if new endpoints have docs)

### Where to Document

In code: Why decisions were made (comments) In repository: How to run, deploy, contribute (README, guides) In API spec: Endpoints, parameters, examples (OpenAPI) In records: Architectural decisions and tradeoffs (ADRs) In runbooks: How to operate the system (step-by-step)

Each place serves a purpose. Use all of them.

### Documentation as Communication

Good documentation is about **communication**.

When you write documentation, you're answering these questions:

- Why does this exist?

- How does it work?

- How do I use it?

- What can go wrong?

- Who do I ask for help?

Answer all five, and you have good documentation.

---

## 🚀 Next Steps

Documentation is a skill that improves with practice.

Week 1: Review your existing project

- Read through your README

- Ask: Would a new person understand this?

- Identify gaps in documentation

Week 2: Write one good example

- Pick an API endpoint or feature

- Write clear documentation for it

- Include working code example

Week 3: Refactor one complex function

- Find a function with bad name or confusing logic

- Refactor to be self-documenting

- Remove comments explaining what it does

- Add one comment explaining why it works this way

Week 4: Create first runbook

- Pick one operational task (deploy, rollback, scale)

- Write step-by-step runbook

- Test it (run through all steps)

- Have teammate review

This builds documentation practice incrementally.

**Remember:** The best documentation is documentation people actually read and use.

Make your documentation so clear that people prefer reading it to asking you questions.

That's the goal.Tags

Related Articles

Design Patterns: The Shared Vocabulary of Software

A comprehensive guide to design patterns explained in human language: what they are, when to use them, how to implement them, and why they matter for your team and your business.

Clean Architecture: Building Software that Endures

A comprehensive guide to Clean Architecture explained in human language: what each layer is, how they integrate, when to use them, and why it matters for your business.

GitFlow + GitOps: The Complete Senior Git Guide for Agile Teams and Scrum

A comprehensive tutorial on GitFlow and GitOps best practices from a senior developer's perspective. Master branch strategy, conflict resolution, commit discipline, merge strategies, documentation, and how to be a Git professional in Agile/Scrum teams.