Design Patterns: The Shared Vocabulary of Software

A comprehensive guide to design patterns explained in human language: what they are, when to use them, how to implement them, and why they matter for your team and your business.

Imagine you’re explaining how to make coffee. You could say: “Take water, heat it until it boils, then pass it through a filter containing ground coffee beans, wait for the water to absorb the flavor and color of the coffee, and finally collect the resulting liquid in a cup.” Or you could simply say: “Make coffee.” Everyone immediately understands what it means, what steps it involves, what result to expect.

Design patterns are exactly that: a shared vocabulary for common solutions to recurring problems in software development. When a developer says “let’s use the Observer pattern here,” another experienced developer immediately visualizes the structure, the responsibilities of each component, how information flows, and what benefits and trade-offs that decision brings.

I’ve seen teams lose weeks discussing how to solve a problem, when that problem already had a well-documented and proven solution. I’ve seen code that clumsily reinvents established patterns, adding unnecessary complexity because the developer didn’t know a better way existed. And I’ve also seen the opposite extreme: code full of patterns applied indiscriminately, turning simple solutions into labyrinths of abstractions.

Design patterns are not magic recipes. They’re not rules you must follow blindly. They’re tools in your toolbox, each appropriate for certain problems, inappropriate for others. Understanding them makes you a better developer, but understanding when not to use them makes you a wise developer.

What Design Patterns Really Are

Before diving into specific patterns, you need to understand what they are and what they aren’t. A design pattern is not code you copy and paste. It’s not a framework or a library. It’s a description of a solution to a problem that occurs repeatedly in different contexts.

Think of design patterns as architectural blueprints. When an architect designs a house, they don’t invent from scratch how to build a staircase. There are established patterns for staircases: straight stairs, spiral stairs, L-shaped stairs. Each has known characteristics, advantages and disadvantages, contexts where it works best. The architect doesn’t need to calculate the optimal angle of the steps each time; that knowledge is already encoded in the pattern.

Similarly, software design patterns encode solutions that have proven to work in practice. They were discovered, not invented. Developers observed that certain problems appeared again and again, and that certain solutions worked better than others. Over time, these solutions were documented, given names, and became shared knowledge of the profession.

“Each pattern describes a problem that occurs over and over again in our environment, and then describes the core of the solution to that problem, in such a way that you can use this solution a million times over, without ever doing it the same way twice”

This quote, originally about architectural patterns, perfectly captures the essence of software design patterns. They’re not rigid templates, but flexible guides you adapt to your specific context.

The Three Fundamental Types of Patterns

Design patterns are traditionally classified into three categories, each addressing a different type of problem. Understanding these categories helps you know where to look when facing a specific challenge.

Creational Patterns: How Objects Are Born

Creational patterns deal with object creation. This sounds trivial, but creating objects the right way can be surprisingly complex. How do you create an object without specifying its exact class? How do you ensure only one instance of a certain class exists? How do you build complex objects step by step?

The problem they solve: When you create objects directly in your code, you’re coupling your code to specific classes. If you need to change which class is instantiated, you have to modify the code. If the creation process is complex, that creation code spreads throughout your application. Creational patterns centralize and standardize object creation.

When you need them:

- When the object creation process is complex

- When you need flexibility over which objects are created

- When you want to control how many instances of a class exist

- When direct creation would couple your code too tightly

Structural Patterns: How Objects Relate

Structural patterns deal with how to compose classes and objects to form larger structures. How do you make objects with incompatible interfaces work together? How do you add functionality to an object without modifying its class? How do you represent complex hierarchies of objects?

The problem they solve: As your system grows, you need different parts to work together. But these parts may have been designed independently, may come from external libraries, or may have conflicting requirements. Structural patterns give you ways to organize and connect these pieces.

When you need them:

- When you need to integrate code you can’t modify

- When you want to add functionality without inheritance

- When you have complex object structures to manage

- When you need to provide a simplified interface to a complex system

Behavioral Patterns: How Objects Interact

Behavioral patterns deal with communication between objects. How do you notify multiple objects when something changes? How do you implement algorithms so they can vary independently? How do you define a family of interchangeable algorithms?

The problem they solve: Interaction between objects can become complex quickly. One object may need to notify many others. An algorithm may need to behave differently depending on context. Behavioral patterns organize these interactions in ways that are flexible and maintainable.

When you need them:

- When multiple objects need to coordinate

- When you want behavior to be interchangeable

- When you have complex algorithms that vary

- When you need flexible communication between objects

Creational Patterns in Depth

Let’s explore the most important creational patterns, understanding not just what they are but why they exist and when to use them.

Singleton: The Only One of Its Kind

The problem: There are certain resources that should only exist once in your application. A database connection. A configuration manager. A logging system. If you create multiple instances, you waste resources, create inconsistencies, or worse, cause conflicts.

The solution: The Singleton pattern ensures a class has only one instance and provides a global point of access to it. The class itself is responsible for tracking its single instance.

How it works: Imagine an office with a single shared printer. You don’t want each employee to have their own printer; you want everyone to use the same one. Singleton works like this:

- The class has a private constructor, no one can create instances directly

- The class has a static variable that stores the single instance

- The class provides a public method to get that instance

- The first time that method is called, it creates the instance

- Subsequent times, it returns the already-created instance

A real case: In an e-commerce system, you have a configuration manager that reads settings from files or environment variables. You don’t want to read these files every time you need a configuration; you’d read the file hundreds of times unnecessarily. Singleton allows you to read the configuration once and share it throughout the application.

ConfigurationManager:

- Has a private constructor

- Maintains configuration in memory

- Provides getInstance() method that:

- If it's the first call: reads files, creates instance, saves it

- If not: returns the saved instance

Use anywhere in the application:

config = ConfigurationManager.getInstance()

port = config.get("server_port")When to use it:

- When exactly one instance must exist

- When that instance must be accessible from multiple parts of the code

- When initialization of that resource is expensive

When not to use it:

- When you don’t really need single instance restriction

- When it hinders testing (Singletons are difficult to mock)

- When it creates hidden global dependencies in your code

Factory Method: Delegating Creation

The problem: Your code needs to create objects, but you don’t want it to depend on the concrete classes of those objects. You want flexibility to decide which specific class to instantiate, perhaps based on configuration, context, or business logic.

The solution: The Factory Method pattern defines an interface for creating objects, but lets subclasses decide which class to instantiate. It delegates creation to specialized methods.

How it works: Imagine a pizzeria. There’s no single pizza recipe; there are Neapolitan pizzas, New York pizzas, Chicago-style pizzas. Each style has its own way of being prepared. Factory Method works like this:

- You define an interface or abstract class that declares a method to create objects

- Concrete subclasses implement that method

- Each subclass decides which concrete class to instantiate

- Client code works with the interface, not with concrete classes

A real case: In a notification system, you can send messages by email, SMS, or push notifications. Each channel has its own implementation, but your business code shouldn’t worry about the details.

NotificationService (abstract class):

- Defines method: createNotifier()

- Uses that method to get a notifier

- Sends messages without knowing what type of notifier it is

EmailNotificationService (subclass):

- Implements createNotifier() to return EmailNotifier

- Configures SMTP server, authentication, etc.

SMSNotificationService (subclass):

- Implements createNotifier() to return SMSNotifier

- Configures SMS provider, credentials, etc.

At runtime:

service = decide which service to use based on user preferences

service.sendNotification("Your order has been shipped")

// The code doesn't know if it's email or SMS, it just worksWhen to use it:

- When you don’t know in advance what types of objects you’ll need

- When you want subclasses to specify which objects to create

- When you want to localize creation logic in one place

When not to use it:

- When you only have one type of object to create

- When creation is trivial and won’t change

- When it adds complexity without clear benefit

Builder: Building Step by Step

The problem: Some objects are complex to create. They have many parameters, some optional, others mandatory. The order of initialization matters. Creating these objects directly results in constructors with dozens of parameters or in partially initialized objects.

The solution: The Builder pattern separates the construction of a complex object from its representation. You build the object step by step, and different builders can create different representations using the same process.

How it works: Imagine building a house. You don’t build it instantaneously; you build it step by step: foundation, structure, walls, roof, installations, finishes. Builder works like this:

- You define a Builder interface with methods to build each part

- You implement concrete builders that build different variants

- Optionally, you use a Director that knows the construction sequence

- Client code uses the builder to specify what it wants

- At the end, you get the complete product

A real case: In a report generation system, different users want different types of reports. Some want PDFs with charts. Others want simple CSVs. Others want interactive HTMLs.

ReportBuilder (interface):

- setTitle(title)

- setDateRange(start, end)

- addSection(name, data)

- addChart(type, data)

- setFormat(format)

- build() -> returns the report

PDFReportBuilder (implementation):

- setTitle: configures title with PDF font

- addChart: generates chart as embedded image

- build: generates PDF with all sections

CSVReportBuilder (implementation):

- setTitle: puts it as first line

- addChart: does nothing (CSV doesn't support charts)

- build: generates CSV file with data

Usage:

builder = choose builder based on user preference

builder.setTitle("Monthly Sales")

builder.setDateRange(january, december)

builder.addSection("Summary", summaryData)

builder.addChart("bars", salesData)

report = builder.build()

// You get the report in the desired formatWhen to use it:

- When an object has many construction parameters

- When you want to create different representations of the same object

- When the construction process must be independent of the parts

- When you want to build immutable objects step by step

When not to use it:

- When the object is simple with few parameters

- When you don’t need different representations

- When a simple constructor is sufficient

Structural Patterns in Depth

Structural patterns help us assemble objects and classes into larger structures while keeping these structures flexible and efficient.

Adapter: The Universal Translator

The problem: You have two pieces of code that need to work together, but they have incompatible interfaces. One expects to receive data in one format, the other provides them in another. Modifying either is not an option because they’re in external libraries, or because you’d break other code that depends on them.

The solution: The Adapter pattern converts the interface of a class into another interface the client expects. It allows classes with incompatible interfaces to work together.

How it works: Think of power adapters when you travel. Your laptop has a type A plug, but in that country the outlets are type C. You need an adapter that takes type A on one side and provides type C on the other. Adapter works the same way:

- You have an interface your client code expects

- You have an existing class with a different interface

- You create an Adapter class that implements the expected interface

- Internally, the Adapter translates calls to the existing class

- The client uses the Adapter as if it were the original interface

A real case: Your application uses a payment service, but you decide to change to another provider. The new provider has a completely different API. You don’t want to change all your business code; you only want to change how payment is processed.

PaymentProcessor (interface your code uses):

- processPayment(amount, cardNumber, cvv)

- refundPayment(transactionId)

OldPaymentService (your current implementation):

- processPayment: calls old provider's API

NewPaymentServiceAdapter (new implementation):

- Wraps NewPaymentService (new provider's API)

- processPayment:

- Takes parameters in your format

- Translates them to the format NewPaymentService expects

- Calls NewPaymentService.charge(...)

- Translates response to your format

- Returns the result

Your business code:

processor = NewPaymentServiceAdapter(newService)

result = processor.processPayment(100, "1234...", "123")

// Your code didn't change, you only changed the adapterWhen to use it:

- When you want to use an existing class with incompatible interface

- When you want to create a reusable class that cooperates with unforeseen classes

- When you need to integrate third-party libraries

- When you want to isolate your code from changes in external dependencies

When not to use it:

- When you can modify the original class

- When the interfaces are already compatible

- When it adds unnecessary complexity

Decorator: Adding Responsibilities Dynamically

The problem: You want to add functionality to individual objects, not to the entire class. Using inheritance would create an explosion of subclasses. You want to be able to combine different functionalities flexibly.

The solution: The Decorator pattern adds responsibilities to an object dynamically. Decorators provide a flexible alternative to inheritance for extending functionality.

How it works: Imagine a coffee. You start with simple coffee. Some customers want milk. Others want milk and sugar. Others want milk, sugar, and cream. Creating a class for each combination would be absurd. Decorator works like this:

- You have a base component (the simple coffee)

- You create decorators that wrap the component

- Each decorator adds its functionality and delegates to the wrapped component

- You can stack multiple decorators

- The client sees everything as the same type of component

A real case: In a logging system, sometimes you want simple logs. Sometimes you want logs with timestamps. Sometimes with timestamps and severity level. Sometimes all of the above plus the name of the user who caused the log.

Logger (base interface):

- log(message)

SimpleLogger (base implementation):

- log: prints the message as is

TimestampDecorator (decorator):

- Wraps a Logger

- log:

- Adds timestamp to the beginning of the message

- Calls logger.log(messageWithTimestamp)

SeverityDecorator (decorator):

- Wraps a Logger

- log:

- Adds severity level

- Calls logger.log(messageWithSeverity)

Flexible usage:

// Simple log

logger = SimpleLogger()

// Log with timestamp

logger = TimestampDecorator(SimpleLogger())

// Log with timestamp and severity

logger = SeverityDecorator(TimestampDecorator(SimpleLogger()))

logger.log("User logged in")

// Output: "[ERROR] 2025-09-30 10:30:45 - User logged in"When to use it:

- When you want to add responsibilities to individual objects

- When extension by inheritance is impractical

- When you want to be able to combine behaviors flexibly

- When you want to be able to add/remove functionality at runtime

When not to use it:

- When the additional behavior is an integral part of the object

- When it creates too many small objects

- When the complexity of stacking decorators is confusing

Facade: Simplifying Complex Interfaces

The problem: You have a complex subsystem with many classes, interfaces, and dependencies. Clients need to interact with this subsystem, but they don’t need to know all its internal details. Exposing all the complexity makes the subsystem difficult to use.

The solution: The Facade pattern provides a unified and simplified interface to a set of interfaces in a subsystem. It makes the subsystem easier to use.

How it works: Imagine a home theater control panel. Behind the panel there’s an amplifier, a DVD player, a sound system, smart lights. To watch a movie, you could configure each component individually, or simply press “Watch Movie.” Facade works like this:

- You have a complex subsystem with multiple components

- You create a Facade class that knows that subsystem

- The Facade exposes simple methods that orchestrate the components

- Clients use the Facade instead of the components directly

- The subsystem remains accessible for advanced needs

A real case: In an e-commerce system, processing an order involves verifying inventory, processing payment, creating shipping record, updating analytics, sending confirmation email. They’re multiple complex subsystems.

OrderProcessingFacade:

processOrder(order):

// Coordinates multiple subsystems

1. inventoryService.checkAvailability(order.items)

2. If insufficient stock:

return error("Insufficient stock")

3. paymentResult = paymentService.charge(order.payment)

4. If payment fails:

return error("Payment declined")

5. inventoryService.reserveItems(order.items)

6. shippingService.createShipment(order.address, order.items)

7. analyticsService.trackSale(order)

8. emailService.sendConfirmation(order.customerEmail)

9. return success(order.id)

Web controller code:

facade = OrderProcessingFacade(...)

result = facade.processOrder(order)

// One line instead of orchestrating 8 servicesWhen to use it:

- When you want to provide a simple interface to a complex subsystem

- When there are many dependencies between clients and implementation classes

- When you want layering in your system

- When you want to decouple subsystems from clients

When not to use it:

- When the subsystem is simple

- When clients need fine-grained control of the subsystem

- When creating the Facade is more complex than using the subsystem directly

Behavioral Patterns in Depth

Behavioral patterns deal with efficient communication and the assignment of responsibilities between objects.

Observer: Notifying Interested Parties

The problem: An object changes state and multiple other objects need to be notified automatically. Making the object know all its dependents creates tight coupling. You want objects to be able to subscribe and unsubscribe dynamically.

The solution: The Observer pattern defines a one-to-many dependency between objects. When an object changes state, all its dependents are notified and updated automatically.

How it works: Think of a newspaper subscription. Readers subscribe, the newspaper maintains a list of subscribers, and when there’s a new edition, it’s sent to everyone. Readers can subscribe or cancel at any time. Observer works like this:

- You have a Subject (the observed) that maintains state

- You have Observers (the observers) who want to know about changes

- Observers register with the Subject

- When the Subject changes, it notifies all registered Observers

- Observers react to the change as they need

A real case: In a financial dashboard, multiple components display information about a stock: a price chart, a percentage change indicator, price alerts. When the stock price updates, all must reflect it.

StockData (observed Subject):

- Maintains current price of a stock

- Maintains list of registered observers

- Methods:

- attach(observer): adds an observer

- detach(observer): removes an observer

- notify(): calls update() on each observer

- setPrice(newPrice):

- Updates the price

- Calls notify()

PriceChartObserver (Observer):

- update(stockData):

- Gets new price

- Redraws the chart

PercentageIndicatorObserver (Observer):

- update(stockData):

- Calculates percentage change

- Updates the indicator

PriceAlertObserver (Observer):

- update(stockData):

- If price crosses a threshold

- Sends alert to user

Initialization:

stock = StockData("AAPL")

stock.attach(PriceChartObserver())

stock.attach(PercentageIndicatorObserver())

stock.attach(PriceAlertObserver(threshold=150))

When new price arrives:

stock.setPrice(152.30)

// Automatically all observers updateWhen to use it:

- When a change in one object requires changing others

- When an object must notify others without knowing who they are

- When you want low coupling between objects

- When you need event broadcasting

When not to use it:

- When there’s only one observer (use direct call)

- When notification order matters

- When the cascade of updates can be complex

Strategy: Swapping Algorithms

The problem: You have a family of related algorithms. You want them to be interchangeable. You don’t want the client to know the details of each algorithm. Changing algorithms shouldn’t require changing client code.

The solution: The Strategy pattern defines a family of algorithms, encapsulates each one, and makes them interchangeable. Strategy allows the algorithm to vary independently of clients that use it.

How it works: Imagine you’re going from point A to point B. You can walk, bike, drive, take public transport. The destination is the same, but the strategy to get there varies. Strategy works like this:

- You define a common interface for all algorithms

- You implement each algorithm as a separate class

- The context maintains a reference to a strategy

- The client can change the strategy at runtime

- The context delegates work to the current strategy

A real case: In an e-commerce system, calculating shipping cost depends on the chosen method: standard shipping is cheaper but slow, express shipping is more expensive but fast, overnight shipping is very expensive but immediate.

ShippingStrategy (interface):

- calculateCost(package) -> returns cost

- estimateDeliveryTime(package) -> returns days

StandardShippingStrategy:

- calculateCost:

- Calculates based only on weight

- Uses economy rate

- estimateDeliveryTime:

- Returns 5-7 days

ExpressShippingStrategy:

- calculateCost:

- Calculates based on weight and distance

- Uses premium rate

- estimateDeliveryTime:

- Returns 2-3 days

OvernightShippingStrategy:

- calculateCost:

- Calculates with very high rate

- Adds urgency charge

- estimateDeliveryTime:

- Returns 1 day

ShoppingCart (context):

- items

- shippingStrategy

setShippingStrategy(strategy):

- Saves the chosen strategy

calculateTotal():

- Sums item prices

- Adds shippingStrategy.calculateCost(items)

- Returns total

Usage:

cart = ShoppingCart()

cart.addItem(product1)

cart.addItem(product2)

// Client chooses standard shipping

cart.setShippingStrategy(StandardShippingStrategy())

total = cart.calculateTotal() // $135

// Client changes to express

cart.setShippingStrategy(ExpressShippingStrategy())

total = cart.calculateTotal() // $155When to use it:

- When you have multiple variants of an algorithm

- When you want to change algorithms at runtime

- When you want to avoid complex conditionals

- When algorithms should be interchangeable

When not to use it:

- When you only have one algorithm

- When algorithms are very similar

- When the client shouldn’t choose the algorithm

Command: Encapsulating Requests as Objects

The problem: You want to parameterize objects with operations. You want to queue operations, log them, or undo them. You want to decouple the object that invokes the operation from the object that knows how to perform it.

The solution: The Command pattern encapsulates a request as an object, allowing you to parameterize clients with different requests, queue requests, log requests, and support reversible operations.

How it works: Imagine a universal remote control. Each button executes a different command: turn on TV, change channel, adjust volume. The remote doesn’t know how each device works; it just sends commands. Command works like this:

- You define a Command interface with an execute() method

- You create concrete commands that encapsulate an action and its receiver

- An invoker maintains commands and executes them

- Commands know which receiver object to call and with what parameters

- Optionally, commands can have an undo() method

A real case: In a text editor, you have operations: write text, delete, copy, paste, format. You want to support undo/redo these operations. Each operation must be reversible.

Command (interface):

- execute()

- undo()

WriteTextCommand:

- Stores: the editor, the text to write, the position

- execute():

- Inserts the text in the editor

- Saves position for undo

- undo():

- Deletes the inserted text

DeleteTextCommand:

- Stores: the editor, the position, the length

- execute():

- Saves the text to delete

- Deletes text from editor

- undo():

- Re-inserts the saved text

FormatTextCommand:

- Stores: the editor, the range, new format, previous format

- execute():

- Applies new format

- undo():

- Restores previous format

TextEditor:

- Maintains two stacks: historyCommands, redoCommands

executeCommand(command):

- command.execute()

- Adds command to historyCommands

- Clears redoCommands

undo():

- Takes last command from historyCommands

- command.undo()

- Moves command to redoCommands

redo():

- Takes last command from redoCommands

- command.execute()

- Moves command to historyCommands

Usage:

editor = TextEditor()

// User writes "Hello"

cmd1 = WriteTextCommand(editor, "Hello", 0)

editor.executeCommand(cmd1)

// User formats as bold

cmd2 = FormatTextCommand(editor, range(0,5), "bold")

editor.executeCommand(cmd2)

// User undoes

editor.undo() // Format is undone

editor.undo() // "Hello" is undone

// User redoes

editor.redo() // "Hello" reappearsWhen to use it:

- When you want to parameterize objects with operations

- When you want to queue, log, or undo operations

- When you want to decouple invoker from receiver

- When you want to support transactions

When not to use it:

- When operations are trivial

- When you don’t need undo/redo

- When it adds unnecessary complexity

When to Use Patterns and When Not To

Design patterns are powerful tools, but they can be misused. I’ve seen code that applies patterns indiscriminately, turning simple solutions into labyrinths of abstractions. I’ve also seen code that desperately needs them but doesn’t use them.

Signs You Need a Pattern

You’re solving a known problem: If your problem sounds familiar, there’s probably a pattern for it. “I need to notify multiple objects when something changes” is Observer. “I need to create objects without specifying their exact classes” is Factory.

You’re repeating code: If you find similar code in multiple places, there’s probably a missing abstraction. Patterns often eliminate duplication by extracting what varies.

Your code is rigid: If changing something requires modifying multiple unrelated places, you probably need better separation of concerns. Patterns help decouple.

Testing is difficult: If you can’t test a component in isolation, it’s probably too coupled. Patterns like Strategy, Observer, and Dependency Injection facilitate testing.

Signs You’re Abusing Patterns

Unnecessary complexity: If you’ve created five classes to solve a problem that required one function, you’re probably over-designing. YAGNI (You Aren’t Gonna Need It) is a valid principle.

Nobody understands the code: If your team needs a UML diagram to understand a simple flow, there are probably too many abstractions. Code should communicate intention.

Simple changes are difficult: Ironically, poorly applied patterns can make code more rigid. If adding a field requires changes in six classes, something is wrong.

You’re applying patterns “just because”: If you can’t articulate what specific problem a pattern solves in your context, you probably don’t need it. Patterns should have clear justification.

The Evolution of Patterns in Your Code

Design patterns are rarely implemented from the beginning. They generally emerge as code evolves and is refactored. This is the natural cycle:

Phase 1: Simple Code

You start with the simplest solution that works. No patterns, no complex abstractions. Just code that solves the immediate problem. This is fine. It’s exactly where you should start.

Phase 2: Identify the Problem

As code grows, you start to see problems: duplication, coupling, rigidity. This is where you pay attention. Is this problem known? Is there a pattern that addresses it?

Phase 3: Refactor Toward the Pattern

Don’t rewrite everything from scratch. Refactor gradually toward the pattern. Move one piece at a time. Keep tests passing. This incremental process is safer and allows you to learn.

Phase 4: Validate the Improvement

Is the code more flexible? Is it easier to understand? Does it facilitate testing? If the answer is yes, the pattern was useful. If not, consider reverting. Not all patterns work in all contexts.

Communicating with Patterns

One of the most underestimated benefits of design patterns is how they improve team communication.

Shared Language

When you say “let’s use Observer for this,” everyone on the team immediately understands the structure, responsibilities, and implications. You don’t need to explain how communication between objects will work; the pattern communicates it.

Implicit Documentation

Code that follows recognizable patterns is self-documenting. A new developer can see classes called “Builder” or “Factory” and understand their purpose without reading documentation.

More Effective Code Reviews

In reviews, you can discuss whether a pattern is appropriate instead of debating implementation details. “Do we really need Strategy here?” is a more productive question than “Why did you create this interface?”

Faster Onboarding

New team members who know patterns can understand large codebases faster. Patterns are familiar reference points in unfamiliar territory.

Resources for Deeper Understanding

Design patterns are a deep topic. This article is an introduction, but there’s much more to explore.

Fundamental Reading

“Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software” by Gang of Four The original book that cataloged the 23 classic patterns. It’s dense and uses Smalltalk/C++, but it’s the foundation of pattern knowledge.

“Head First Design Patterns” by Freeman and Freeman Much more accessible than Gang of Four. Uses Java but concepts are universal. Excellent for beginners.

“Refactoring to Patterns” by Joshua Kerievsky Shows how to evolve existing code toward patterns. Extremely practical.

Related Concepts

SOLID Principles The principles underlying many patterns. Understanding SOLID helps you understand why patterns work.

Domain-Driven Design Complements patterns by focusing on correctly modeling the business domain.

Clean Code Patterns are part of writing clean code, but they’re not everything. This book provides the broader context.

Deliberate Practice

Refactoring Kata Small exercises where you practice identifying problems and applying patterns. The Gilded Rose Kata is excellent.

Code Reviews Pay attention to patterns in code reviews. Both when they’re absent and when they’re present.

Open Source Projects Read code from well-designed projects. Frameworks like Spring, Django, or Rails use patterns extensively.

Design patterns are not magic recipes or absolute rules. They’re lessons learned by generations of developers, codified in reusable form. Some will solve problems you face today. Others prepare you for problems you’ll face tomorrow.

I’ve seen teams transform by adopting patterns. Code that was a mess becomes maintainable. Communication that was confusing becomes clear. Developers who were reinventing the wheel start building on established knowledge.

But I’ve also seen the damage caused by poorly applied patterns. Simple code turned into labyrinths of abstractions. Developers more concerned with using patterns “correctly” than solving real problems. Solutions that look elegant in UML diagrams but are nightmares to maintain in production.

The wisdom is in balance. Learn the patterns. Understand their trade-offs. Use them when they solve real problems. Don’t use them just because you know them. And remember: the best code is often the simplest that works.

“Design is the art of balancing conflicting forces toward an optimal result”

Your job isn’t to memorize patterns. Your job is to understand problems deeply and choose appropriate solutions. Sometimes that solution is an established pattern. Sometimes it’s something completely new. The difference between a junior and a senior developer isn’t how many patterns they know, but how well they know when to apply them and when not to.

Design patterns are a shared vocabulary. Use it to communicate with your team. Use it to learn from the accumulated experience of thousands of developers. But never lose sight that they’re means to an end, not the end itself. The end is software that solves real problems in a maintainable, flexible, and understandable way.

That’s the real purpose of patterns: helping you write better software, not more complicated software.

Tags

Related Articles

Clean Architecture: Building Software that Endures

A comprehensive guide to Clean Architecture explained in human language: what each layer is, how they integrate, when to use them, and why it matters for your business.

gRPC: The Complete Guide to Modern Service Communication

A comprehensive theoretical exploration of gRPC: what it is, how it works, when to use it, when to avoid it, its history, architecture, and why it has become the backbone of modern distributed systems.

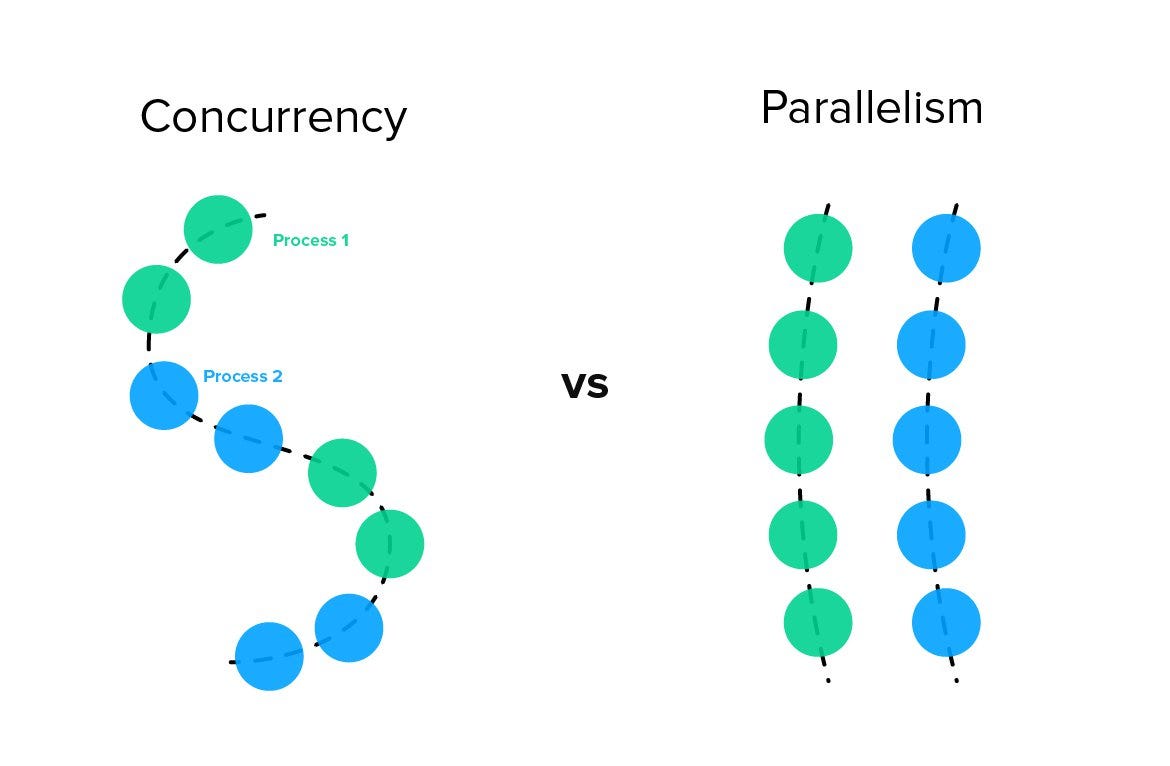

Concurrency vs Parallelism: Understanding the Paradigm That Powers Modern Software

A deep exploration of concurrent and parallel programming: what they are, how they differ, common pitfalls, real-time considerations, and the mental models needed to build robust modern systems.