The Ideal Scrum + Agile Workflow: A Developer's Complete Guide Through Every Ceremony and Stage

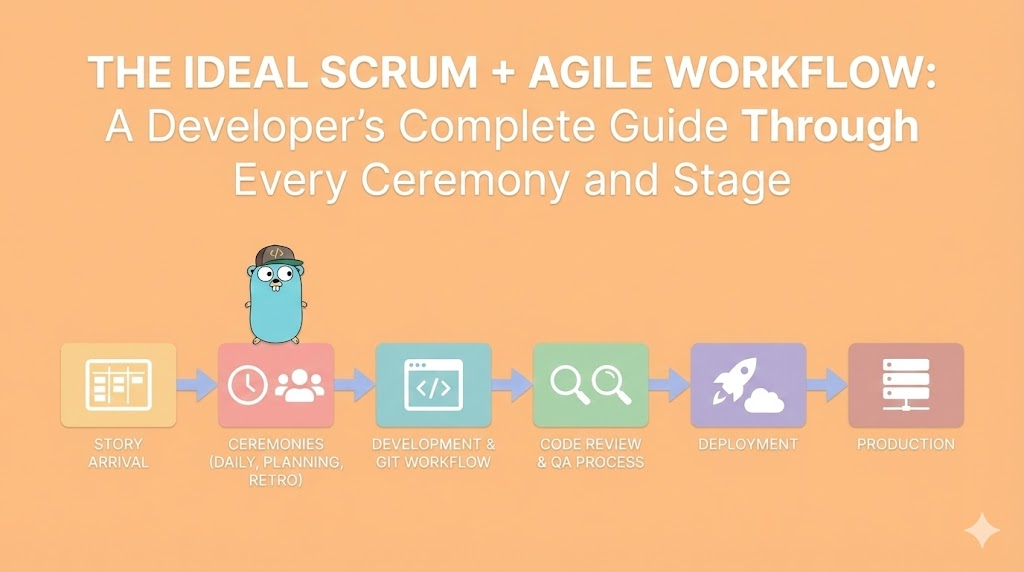

A comprehensive guide to the ideal Scrum and Agile workflow from a developer's perspective. From story arrival through production deployment, understanding every ceremony, role, decision point, and what should actually happen at each stage.

The Ideal Scrum + Agile Workflow: A Developer’s Complete Guide Through Every Ceremony and Stage

From Story Arrival to Production Deployment: What Should Actually Happen

🎯 Introduction: Why Most Teams Do Scrum Wrong

Let me be direct: Most development teams do Scrum wrong.

Not intentionally. Not maliciously. But systematically.

They have standups without focus. They have retros that change nothing. They have code reviews that are rubber stamps. They have deployments that are chaotic. And they wonder why velocity is unpredictable and quality is inconsistent.

The truth is simple: Scrum and Agile are not processes you implement. They are rhythms you establish.

Think of it like a musician learning an instrument. You don’t just know the notes. You internalize the rhythm. You feel the beat. You know when something is off. The Scrum workflow is the same.

What This Guide Is About

This is not a theoretical guide. This is not “Scrum best practices according to the Scrum Guide.”

This is: What should actually happen at each stage of a real sprint, from the perspective of a developer who cares about their work.

We will cover:

✅ How stories should actually arrive in your backlog

✅ What sprint planning should look and feel like

✅ How to structure your work during the sprint

✅ What daily standups are actually for

✅ How Git workflow supports Agile, not hinders it

✅ What code review should be (spoiler: not gatekeeping)

✅ How QA fits into continuous delivery

✅ What “Definition of Done” really means

✅ How to handle production deployment

✅ What retros should actually accomplish

✅ The complete cycle, and how it compounds

The Perspective: A Developer’s View

This guide is written for developers, by someone who understands development.

You will not read: “Send a message to Slack saying the story is done.”

You will read: “Here’s why this decision matters, what happens if you skip this step, and how it affects your quality.”

📋 Part 1: The Story Arrives - Product Backlog Refinement Phase

This is where everything starts. A story doesn’t just magically appear in your sprint. There’s a process before that.

What Happens Before You See It: Backlog Refinement

Before a story reaches your sprint, it should go through backlog refinement. This is critical and often skipped.

When: Typically 1-2 sprints before it enters the current sprint, or continuously

Who: Product Owner, Senior Developers, potentially the whole team

Duration: Usually 30-60 minutes per session, 1-2 sessions per week

What actually happens in refinement:

The Product Owner brings raw ideas. These are not well-formed stories yet. They’re more like:

"Users should be able to export data"

"The dashboard is slow"

"We need better error messages"

"Integrate with Stripe"The team’s job is to transform these ideas into stories that can be estimated and implemented.

The Anatomy of a Well-Refined Story

A properly refined story has several components:

1. Clear User Value

Not: “Create an API endpoint”

But: “As a user, I want to export my data as CSV so I can analyze it in Excel”

Why this matters: It keeps the developer focused on why they’re building this, not just what they’re building.

2. Acceptance Criteria

These are testable conditions that define when the story is done.

Example:

Story: Export data as CSV

Acceptance Criteria:

☐ CSV file contains all user records

☐ CSV includes columns: id, name, email, created_date, status

☐ File is generated within 5 seconds

☐ Users receive file download in browser

☐ File is named: export_{timestamp}.csv

☐ Sensitive fields (password, API keys) are NOT includedWhy this matters: You now have objective criteria for doneness. No ambiguity.

3. Technical Notes / Considerations

The team identifies technical complexity upfront:

Technical Considerations:

- May need to optimize database query for large datasets

- CSV generation can use existing export library (CsvHelper)

- Consider implementing this as background job if > 100k records

- Need to add IAM permission for S3 if async approachWhy this matters: It prevents surprises during sprint. The developer knows what they’re getting into.

4. Estimation

The team estimates the story in story points (or time, but points are better).

Estimation: 8 points

Reasoning:

- 3 points: Database query and filtering

- 2 points: CSV generation and formatting

- 2 points: File download mechanism

- 1 point: Testing and edge casesWhy this matters: You have a shared understanding of scope and effort before starting.

5. Dependencies Identified

Depends on:

- Story #123: User roles and permissions

- Story #124: Database optimization for large queries

Blocks:

- Story #456: Advanced analytics (which uses exported data)Why this matters: Sprint planning becomes predictable. You avoid: “Oh, we can’t do this because X isn’t done.”

What Happens to Refined Stories

After refinement, stories sit in the Product Backlog, ordered by priority.

The Product Owner is constantly prioritizing:

Top 5 (likely in next 1-2 sprints):

1. Fix critical production bug (P0)

2. Implement user authentication (blocks many features)

3. Create admin dashboard (business need)

4. Export data as CSV (nice to have, but refined)

5. Improve search performance (technical debt, but will help users)

Middle (might be in next 4-6 weeks):

- Integrate with Stripe

- Add multi-language support

- Create API documentation

- ...

Bottom (backlog of nice-to-haves):

- Dark mode

- Mobile optimizations

- Analytics enhancements

- ...🏃 Part 2: Sprint Planning - How a Story Enters Your Current Sprint

Now the story is refined and prioritized. Sprint planning happens.

Sprint Planning Meeting: The Setup

When: Start of sprint (typically Monday morning)

Duration: 1-2 hours for 2-week sprint (proportional to sprint length)

Who: Entire development team, Product Owner, Scrum Master

Output: A sprint backlog with committed stories and tasks

What Happens Step-by-Step

Step 1: Product Owner Presents the Priorities

The Product Owner doesn’t dictate. They present and discuss.

PO: "Here are the top stories for this sprint:

1. Fix payment processing bug (P0 - customer complaint)

2. Export data as CSV (8 points)

3. Improve homepage load time (5 points)

4. Add API rate limiting (5 points)

5. Create admin dashboard (13 points)

We'd like to get 1, 2, 3, 4 in. 5 is stretch if we finish others early."The team listens and asks clarifying questions:

Developer A: "On the payment bug - how often is it happening?"

Developer B: "For the export CSV - what's the maximum file size we expect?"

Developer C: "For the dashboard - is this the full dashboard or MVP?"Why this matters: Questions here prevent misunderstandings later. They also help the estimation phase.

Step 2: The Team Discusses Capacity

The team is honest about what they can actually do:

Team capacity for 2-week sprint:

Total team points available: ~40 points

(5 developers × 2 weeks × 4 points per person per week average)

Minus unavoidable commitments:

- Bob is on vacation Wed-Fri (loses 5 points)

- Sarah is mentoring a new dev (loses 3 points)

- 1 person always on support rotation (loses 2 points)

- Meetings, interruptions, etc (losses 3 points)

Realistic capacity: ~27 points

PO's request: ~36 points (export CSV 8 + dashboard 13 + others 15)

Gap: We're overbooked by ~9 pointsThis is a crucial conversation. The team is not rude. Not saying “no”. They’re being honest.

Team: "We can take export CSV, homepage performance, and rate limiting.

The dashboard is 13 points and we only have 11-12 left.

We could split it: do the user dashboard this sprint (8 points),

admin features next sprint (5 points)?"

PO: "OK, let's split it. User dashboard this sprint, admin features next."Why this matters:

If the team pretends they can do 36 points with 27 points of capacity, they:

- Work weekends (burnout)

- Cut corners on testing (bugs)

- Commit to work they don’t deliver (looks bad)

- Feel like failures (demotivating)

Honesty about capacity is professional responsibility, not lack of ambition.

Step 3: The Team Commits to the Sprint

Once scope is agreed:

Sprint Backlog for Sprint 16 (Jan 20 - Feb 2):

Story 1: Payment processing bug fix (5 points) - ASSIGNED: Bob

Story 2: Export data as CSV (8 points) - ASSIGNED: Alice

Story 3: Improve homepage load time (5 points) - ASSIGNED: Carlos

Story 4: Add API rate limiting (5 points) - ASSIGNED: Sarah

Story 5: User dashboard (8 points) - ASSIGNED: David + Alice

Total: 31 points

Capacity: 27 points

Stretch: 4 points (OK for stretch goal)Each story is assigned to the primary developer who will implement it. This doesn’t mean solo work. It means they’re accountable.

The team says: “We commit to finishing these stories by the end of the sprint.”

Not “trying to finish.” Not “hoping to finish.” Committing to finish.

Step 4: Breaking Stories into Tasks

For larger stories, the team breaks them down into tasks.

Example: “Export data as CSV” (8 points)

Tasks:

☐ Create database query for data export (backend dev task)

☐ Implement CSV generation logic (backend dev task)

☐ Create API endpoint for export (backend dev task)

☐ Create frontend export button and trigger (frontend dev task)

☐ Add error handling for large exports (backend dev task)

☐ Write tests for CSV generation (testing task)

☐ Test end-to-end workflow (QA task)

☐ Code review (code review task)Each task is estimated in hours or sub-points, not story points.

Tasks help developers see what’s required and track progress during the sprint.

The Commitment is Sacred (But Not Rigid)

Once the team commits to a sprint, this is sacred ground.

Developers now focus on these stories. They don’t switch contexts. They don’t pick up random “urgent” requests.

But commitment is not rigidity.

If a developer discovers something unexpected:

Developer: "The payment bug is more complex than we thought.

It's going to take 13 hours instead of 5."

Scrum Master: "OK. What should we pull out to make room?"

Options:

A) Reduce scope of the payment bug (maybe don't fix all edge cases)

B) Move the rate limiting story to next sprint

C) Move to split the dashboard work differently

Team decides: Pull rate limiting to next sprint, focus on payment bug.This is healthy adaptation, not failure.

💼 Part 3: Story Development - From Code to Pull Request (The Daily Reality)

The story is now in the sprint. It’s assigned to you (or you’re helping implement it).

Now what?

Day 1: Understanding the Story

You don’t start coding immediately. First, you understand deeply.

Read and Re-read the Story

Read it carefully:

Story: Export data as CSV

Description:

As a user, I want to export my data as CSV so that I can analyze it in Excel

Acceptance Criteria:

☐ CSV file contains all user records

☐ CSV includes columns: id, name, email, created_date, status

☐ File is generated within 5 seconds

☐ Users receive file download in browser

☐ File is named: export_{timestamp}.csv

☐ Sensitive fields (password, API keys) are NOT included

Technical Considerations:

- Use CsvHelper library (already in project)

- Consider background job if > 100k records

- Add logging for export events

- Handle special characters in dataYou read this multiple times. You note ambiguities:

Questions I have:

- What if user has 0 records? Do we show error or empty CSV?

- What about users with special characters in names (José, François)?

- Performance: 100k records should generate in < 5 seconds.

What if it takes 10 seconds? Do we timeout or show progress?

- Security: What if someone requests another user's data?Ask for Clarification

Before coding, you ask:

Developer: "I have some questions on the export CSV story:

1. What if the user has no data - show error or empty file?

2. How should we handle special characters?

3. Should large exports (>50k records) be background jobs?

4. How do we prevent users from exporting other users' data?"

PO: "Good questions!

1. Show empty file, not error - users might expect that

2. Use UTF-8 encoding, should handle most cases

3. Yes, >50k records should be background job with email delivery

4. Use current user's ID for security - only export own data"This conversation prevents rework later. It’s not laziness. It’s diligence.

Plan Your Approach

Now you create a mental model of how you’ll implement this:

My approach:

1. Add "Export" button to the user data page (frontend)

2. Click triggers POST /api/export/csv (backend)

3. Backend validates: user is authenticated, only exporting own data

4. If < 50k records:

- Generate CSV in-memory

- Return as download

- Response within 5 seconds

5. If >= 50k records:

- Create background job

- Send email with download link when ready

- Return message: "Large export started, we'll email you"

6. Add logging for audit trail

7. Write tests for both pathsYou don’t code this yet. You’ve just planned it. This takes 30 minutes, saves 4 hours later.

Day 2-3: Creating the Feature Branch

Before coding, you create a Git branch:

git checkout -b feature/export-data-csvWhy not code on main or develop? Because isolation prevents chaos.

The branch naming convention is important:

feature/export-data-csv ← New feature

bugfix/payment-processing ← Bug fix

hotfix/security-patch ← Critical production fix

refactor/database-queries ← Code cleanup, no behavior changeThe branch exists only for this story. Nothing else.

Day 2-3: Implementation

Now you code. You follow the team’s coding standards:

Our standards (example):

✅ Write tests as you code (not after)

✅ Keep functions < 30 lines

✅ Use meaningful variable names

✅ Add comments for "why", not "what"

✅ Follow existing project patterns

✅ No console.log in production code

✅ Handle errors explicitlyAs you code, you might discover:

"Oh, the database queries for large exports are slow.

I need to add an index. That's a separate concern."

So you:

1. Create a subtask: "Add database index for user_id on records table"

2. Implement that first

3. Then implement the export featureOr:

"The CSV library doesn't handle special characters well.

I need to use a different approach."

So you:

1. Update the story description with technical note

2. Mention it in daily standup

3. Implement a better solutionThis is normal. You’re discovering as you go. The key is communicating these discoveries.

Commits: The Art of Good Git History

As you code, you commit regularly. Your commits tell a story:

Commit 1: "Add data export endpoint skeleton"

Commit 2: "Implement CSV generation logic"

Commit 3: "Add authentication check for export"

Commit 4: "Add support for background jobs for large exports"

Commit 5: "Add tests for CSV generation"

Commit 6: "Add integration tests for export endpoint"Each commit:

- ✅ Represents a logical unit of work

- ✅ Has a clear message

- ✅ Could be reverted independently if needed

- ✅ Passes tests (ideally)

Bad commits:

Commit 1: "WIP - stuff"

Commit 2: "WIP again"

Commit 3: "Finally works lol"

Commit 4: "Adding tests I forgot"These commits make code review hard. They make debugging hard. They make history unintelligible.

Your Git history is part of your code quality.

Subtasks and Decomposition

As you implement, you update the task list in the story:

[Original Sprint Backlog]

Story: Export data as CSV (8 points)

Tasks:

☑ Create database query for data export

☑ Implement CSV generation logic

☐ Create API endpoint for export

☐ Create frontend export button

☑ Add error handling for large exports

☐ Add database index for performance

☑ Write tests for CSV generation

☐ Write integration tests

☐ Code reviewThe task list shows progress. It’s not just for tracking. It’s for morale. When you see checkmarks accumulating, it feels like progress.

When You’re Stuck

If you get stuck:

Stuck situation: "I can't figure out how to handle

special characters in CSV without breaking the format"

What NOT to do:

❌ Ignore it and move on (create bugs)

❌ Spend 4 hours debugging alone

❌ Pretend it works

What TO do:

✅ Stop and ask for help (5 minutes to explain)

✅ Pair with someone else (find solution together)

✅ Look up documentation / examples

✅ Ask in Slack immediately, don't wait for daily standupTeams that help each other are faster. Not slower.

📊 Part 4: The Daily Standup - The Heartbeat of the Sprint

If the sprint is a body, the daily standup is the heartbeat. It happens every single day at the same time, in the same place (physical or virtual).

What Time and Why It Matters

The standup usually happens early morning (9:00 AM or 10:00 AM).

Why early?

✅ Catches blockers before the day starts

✅ Allows people to unblock each other immediately

✅ Prevents team from going in different directions

✅ Maintains momentum from day before

✅ Teams that standup early ship fasterThe time is sacred. Not negotiable. If it’s at 9:15 AM, it starts at 9:15 AM, not 9:20 AM.

Why? Because when timing is flexible, it becomes: 9:20, 9:30, sometimes skipped. Then communication breaks down.

Duration: 15 Minutes Maximum

The standup is time-boxed to 15 minutes. Not 20. Not 30. Fifteen.

Why?

- Teams with long standups = poor communication structure

- If you can't cover it in 15 min, something is wrong

- Longer standups = people tune out

- 15 min forces discipline in what you discussIf a topic needs more discussion, you schedule a separate conversation after standup, not during.

Who Participates

Essential:

- All developers currently in the sprint

- Scrum Master

- Product Owner (optional but recommended)

Not essential:

- Executives observing

- Random colleagues from other teams

- Interruptions allowed

The standup is for the team, not for status reporting to management.

What NOT to Do in Standup

Before I explain what to do, let me be clear about what NOT to do:

❌ Status Report Format

DO NOT say:

"Yesterday I completed task 1. Today I'm working on task 2.

No blockers."

"I spent 4 hours on database optimization.

I'll spend 4 hours on frontend work today.

Everything is on track."This is reporting to a manager, not syncing as a team.

❌ Detailed Technical Explanations

DO NOT say:

"I found a race condition in the async queue handler where

the Promise rejection wasn't being caught by the middleware,

so I refactored the entire promise chain to use async/await,

and now I'm concerned about the timeout configuration..."This is not the forum for this. Details later.

❌ Self-Assessment

DO NOT say:

"I'm making good progress. I feel good about the story.

I think I'll finish on time."This is vague. It’s not objective.

❌ Excuses or Over-Explanation

DO NOT say:

"I didn't finish the API tests yesterday because the database

was slow and I had to reboot my laptop and then I got sick

and also the Slack notifications kept distracting me..."No one cares. Status is status.

What TO Do: The Three Questions

The standup has three questions. Each developer answers all three:

Question 1: What Did I Finish Yesterday?

Answer format:

"I finished the CSV generation logic and wrote tests for it.

That task is complete."

or

"I made progress on the export endpoint - got the authentication

working and the data filtering, but didn't complete the background

job logic yet."

or

"I was blocked on the database index, so I helped Sarah with

code review instead."Key: Be specific. Mention actual tasks, not vague progress.

Question 2: What Am I Working on Today?

Answer format:

"Today I'm continuing the export endpoint. I'll implement

the background job logic and get tests written."

or

"Today I'm starting the rate limiting story. I'm going to

review the acceptance criteria and set up the API gateway configuration."

or

"I'm pairing with Carlos on the payment bug today. We need to investigate

the transaction logs."Key: Specific work. Not “continuing what I was doing.”

Question 3: Do I Have Any Blockers?

Answer format:

"No blockers, I can continue."

or

"I'm waiting on the database index that's in code review.

Can't test my export feature without it."

or

"I need access to the staging environment API keys.

Can the DevOps team help?"

or

"I'm not sure about the CSV encoding. Can someone point me to

how we've handled this before?"Key: Specific blockers. Actionable.

The Flow

The standup flow is:

Scrum Master: "Good morning. Let's do our standup.

Who wants to go first?"

Developer 1: "I finished the payment bug fix yesterday.

Today I'm writing tests for it. No blockers."

Developer 2: "I made progress on the export CSV feature -

got the backend endpoint done. Today I'm working on the frontend

button and testing. Blocked: waiting on the design specs for the export button."

Product Owner: "I can get you those specs in 30 minutes."

Developer 2: "Thanks, that works."

[Continue around the team]

Scrum Master: "Great. We have a blocker on design specs -

that's being handled. Anyone else notice we're all moving? Good."Total time: 8 minutes.

What Happens After Standup

After standup, the team disperses to work.

If there was a blocker mentioned:

Developer A: "You mentioned you're blocked on the database index.

Let me check the PR status."

Code Reviewer: "Oh, I'll review it right now."This happens in Slack or a quick conversation. Not in standup.

If there was unclear work:

Product Owner: "You said 'staging environment API keys'.

Is that something we need to fix, or just for testing?"

Developer: "Just for testing staging. Let me handle it."Again, quick conversation outside standup.

The Standup is Not a Status Report

Let me emphasize this again because it’s crucial:

The standup is not reporting to a manager. It’s the team aligning.

If your standup feels like you’re reporting to a boss, your standup is wrong. The Scrum Master should facilitate team alignment, not status collection.

If you skip standup for a “meeting with the boss,” that’s backwards. The standup is more important than the meeting with the boss.

Teams that take standup seriously move faster. Teams that treat it as optional stall.

🔀 Part 5: Git Workflow - How Branching Supports Agile

Now you’re implementing your story. The code needs to flow from your laptop to production safely.

Git workflow is not about Git. It’s about team communication and safety.

The Branch Strategy: Feature Branches

Most mature teams use feature branches (or GitFlow variant):

main (production-ready code)

↓

develop (staging, next release)

↓

feature/export-csv (your story branch)Each developer works on a feature branch, never directly on develop or main.

Creating Your Feature Branch

When you start a story, you create a branch:

# First, make sure you're on develop and it's up to date

git checkout develop

git pull origin develop

# Create your feature branch

git checkout -b feature/export-data-csvThe branch name is descriptive:

✅ Good:

feature/export-data-csv

feature/fix-payment-timeout

feature/add-user-authentication

refactor/database-connection-pooling

❌ Bad:

feature/work-in-progress

feature/new-stuff

feature/fix-bug

feature/alice-changesCommits: Granular and Meaningful

As you code, you commit regularly. Each commit should be:

1. Logically complete - One thing per commit

Bad:

commit 1: "Add export endpoint, CSV generation, tests, and fix unrelated bug"

Good:

commit 1: "Add data export endpoint skeleton"

commit 2: "Implement CSV generation logic"

commit 3: "Add authentication for export"

commit 4: "Fix unrelated bug in user lookup" (separate PR)2. Tested - Each commit should not break tests

❌ Don't do this:

commit 1: "Add endpoint (will break tests)"

commit 2: "Fix endpoint (tests pass now)"

✅ Do this:

commit 1: "Add endpoint with tests (tests pass)"3. Well-described - Commit message explains why, not what

❌ Bad message:

"Added CSV logic"

"Fixed stuff"

"WIP"

✅ Good message:

"Implement CSV generation with UTF-8 encoding

Use CsvHelper library to generate CSV files.

Handles special characters (accents, unicode) correctly.

Tested with mock data including edge cases.

Fixes: #432"The commit message has:

- One-line summary (what you did)

- Blank line

- Detailed explanation (why you did it, context)

- Reference to issue/story (Fixes #432)

Pushing to Remote

You push your branch to the remote repository:

git push origin feature/export-data-csvThis does several things:

✅ Backs up your work (you’re not just on your laptop) ✅ Makes your branch visible to the team ✅ Enables code review ✅ Triggers automated tests (CI/CD)

You push regularly, not just when done:

Day 1: git push (3 commits)

Day 2: git push (5 more commits)

Day 3: git push (ready for review, 10 total commits)This is normal and expected.

Keeping Your Branch Updated

While you’re working, the develop branch is being updated by other developers.

After 2-3 days, your branch might be out of sync:

# Fetch latest from develop

git fetch origin

# Rebase your work on top of latest develop

git rebase origin/develop feature/export-data-csvWhy rebase, not merge?

Rebase keeps your commit history clean and linear. Your commits appear on top of develop, in order. This makes code review easier and history easier to read.

With merge:

develop: A -> B -> C

your branch: D -> E -> F -> Merge commit M

Result: A -> B -> C -> D -> E -> F -> M (messy)

With rebase:

develop: A -> B -> C

your branch: D' -> E' -> F' (replayed on top of C)

Result: A -> B -> C -> D' -> E' -> F' (clean)If there are conflicts during rebase, you resolve them and force-push:

# After resolving conflicts

git add .

git rebase --continue

# Force push to your branch (OK because it's your feature branch)

git push origin feature/export-data-csv --forceWhen You’re Done: The Pull Request

When the story is complete and tested, you create a Pull Request (PR).

On GitHub (or GitLab, Bitbucket):

Title: "Add export data as CSV feature"

Description:

## What does this PR do?

Adds ability for users to export their data as CSV file.

## Acceptance criteria

- ✅ CSV contains all user records

- ✅ File includes columns: id, name, email, created_date

- ✅ Sensitive fields excluded

- ✅ File downloads in browser

- ✅ Large exports (>50k records) handled as background jobs

## How to test

1. Log in as a user

2. Click "Export Data" button

3. File downloads as CSV

4. Open in Excel to verify formatting

## Related story

Fixes #234The PR description is crucial. It tells reviewers:

✅ What changed and why ✅ How to test it ✅ What to pay attention to ✅ Links to requirements

PR Etiquette and Responsibilities

When you create a PR, you’re asking your team to review your code. Treat this respectfully.

As the Author:

✅ Make it reviewable - Not 5,000 lines. Break into smaller PRs if needed.

Bad: One PR with 50 files changed

Good: 3-4 focused PRs that build on each other✅ Make it testable - Describe how to test clearly

✅ Respond promptly to review - Don’t let PR sit for days with feedback

✅ Don’t be defensive - Feedback is about code, not you

Reviewer: "Why did you use a loop here instead of map()?"

❌ Don't say: "Because I wanted to. It works fine."

✅ Do say: "I used a loop for clarity, but map() is more idiomatic. I'll refactor."🔍 Part 6: Code Review - The Quality Gate That Actually Works

Your PR is created. Now it goes to code review.

Code review is not punishment. It’s team learning.

What Code Review Is

Code review is when experienced developers read your code and ask questions:

"Why did you choose this approach?"

"Did you consider this edge case?"

"Have you tested this with large data?"

"Can you simplify this?"

"This pattern is different from what we use elsewhere - intentional?"The goal is not to find problems. The goal is to ensure the team understands and agrees with the solution.

Who Reviews

Ideally: 2 developers review your code

Minimum: 1 developer (someone senior or knowledgeable in that area)

Never: The person who wrote it reviews it (conflict of interest)

Example review team for "Export CSV" feature:

Primary reviewer: Sarah (backend expert, wrote our API patterns)

Secondary reviewer: David (knows database performance)

Both must approve before merging.The Review Process: What Reviewers Do

Step 1: Read the PR Description

Before reading code, reviewers read your description:

"OK, they're adding CSV export.

Let me check the acceptance criteria:

- All records ✅

- Specific columns ✅

- No sensitive fields ✅

- Browser download ✅

- Large exports async ✅

I'll look for these things in the code."Step 2: Review the Tests

Next, reviewers look at tests:

Do you have tests for:

✅ Normal case (small export)

✅ Edge cases (no data, special characters)

✅ Large export (background job path)

✅ Security (users can't export others' data)If tests are weak, the review stops there:

Reviewer: "I don't see tests for the large export path.

How do we know that works? Please add tests, then we'll review the implementation."Step 3: Review the Implementation

Only after tests look good, reviewers read the actual code:

Looking at:

- Does it follow our patterns? (architecture)

- Is it readable? (naming, structure)

- Does it handle errors? (error handling)

- Is it efficient? (performance)

- Did you remember security? (no SQL injection, auth checks)Reviewers ask specific questions:

"On line 47, why are you querying all records instead of filtering in SQL?"

"This tries to generate CSV in memory. Won't that break for 100k records?"

"I don't see where you're validating that the user owns this data.

Could a user export another user's data?"

"This is good, but we do pagination similarly in two other places.

Could you extract this to a shared helper?"What Good Code Review Comments Look Like

Bad Review Comments:

"This is bad."

"Why did you do this?"

"This won't work."

"Fix this."

"😕"These are unhelpful and demoralizing.

Good Review Comments:

"I'm concerned about memory usage here. For a user with 100k records,

this will try to load everything into memory.

Consider:

1) Streaming the CSV generation

2) Breaking into chunks

3) Using a background job (which you do for 50k+, so maybe lower threshold?)

What were your thoughts on this?"

---

"I notice you're checking permissions here with a simple userId comparison.

That should work, but consider using the existing AuthorizationService

that we use elsewhere. It has tests for edge cases (admin users, etc.)

that your direct comparison doesn't handle."

---

"Nice test coverage! One edge case: what happens if a record has a comma

in the name and it's not escaped? Have you tested with Excel to make sure

it imports correctly?"These comments: ✅ Explain the concern ✅ Suggest solutions (not dictate) ✅ Reference team patterns ✅ Respect the developer

The Review Cycle

Code review is not one-and-done:

Day 1:

Author creates PR

Reviewers request changes

Day 2:

Author responds to comments

Author makes updates

Author pushes new commits

Day 3:

Reviewers re-review

If still issues: back to author

If approved: merge!Sometimes there are multiple rounds. That’s normal and healthy.

Approval and Merging

Once both reviewers approve:

Reviewer 1: "Approved ✅"

Reviewer 2: "Approved ✅"

Author: "Great. Merging to develop."

git merge develop

git branch -d feature/export-data-csv

git push origin developThe feature branch is deleted. The code is now on develop.

Code Review as Culture

Teams that take code review seriously have:

✅ Fewer bugs in production ✅ Shared knowledge (everyone understands the codebase) ✅ Consistent architecture (patterns enforced through review) ✅ Developers learn from each other

Teams that skip code review have:

❌ More production bugs ❌ Silos (one person knows one area) ❌ Architectural decay (everyone does it differently) ❌ Knowledge loss when people leave

✅ Part 7: Testing and QA Phase - What Done Actually Means

Your code is approved and merged to develop. Is it done?

No. Quality assurance is next.

Types of Testing (And Who Does Them)

There are three layers of testing:

Layer 1: Unit Tests (Developer’s Responsibility)

Unit tests verify small pieces in isolation:

Example unit tests for CSV export:

Test 1: CSV generation formats headers correctly

Test 2: CSV generation handles special characters

Test 3: CSV generation excludes sensitive fields

Test 4: Authentication check blocks unauthorized users

Test 5: Large export (>50k records) returns async response// Example unit test

test("CSV generation excludes password field", () => {

const data = [

{ id: 1, name: "John", email: "john@example.com", password: "secret" },

];

const csv = generateCsv(data);

expect(csv).toContain("id,name,email");

expect(csv).not.toContain("password");

expect(csv).not.toContain("secret");

});Developer responsibility: Write these as you code. Not after.

Layer 2: Integration Tests (Developer’s Responsibility)

Integration tests verify how pieces work together:

Example integration tests:

Test 1: User clicks export button → API called → CSV generated → File downloaded

Test 2: Large export → Background job created → Email sent with download link

Test 3: Permission denied → User can't access another user's export// Example integration test

test("User can export data end-to-end", async () => {

// Create test user

const user = await createTestUser();

// Create test data

await createTestRecords(user.id, 100);

// Call export endpoint

const response = await request("/api/export/csv")

.set("Authorization", user.token)

.expect(200);

// Verify response

expect(response.body.status).toBe("processing");

// Wait for job to complete

await waitForBackgroundJob(response.body.jobId);

// Verify CSV was generated

const csv = await getGeneratedCsv(response.body.jobId);

expect(csv).toContain("id,name,email");

});Developer responsibility: Write these for critical paths.

Layer 3: End-to-End Tests (QA’s Responsibility, But Developers Help)

End-to-end (E2E) tests verify real user workflows in production-like environments:

Example E2E tests:

Test 1: Sign in → Navigate to data page → Click export → File downloads → Open file

Test 2: Sign in → Request large export → See "processing" message → Receive email → Click link → Download

Test 3: Attempt to access another user's export → Permission denied errorE2E tests are slow and expensive, so teams run them:

- Before releasing to staging

- Before releasing to production

- On a schedule (nightly)

QA responsibility: Write and execute these.

The Testing Pyramid

E2E Tests

▲

▀▀▀

/ \

/ \

/ Integration Tests \

▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀

/ \

/ \

/ Unit Tests \

▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀Most tests should be unit tests (fast, cheap).

Some tests should be integration tests (verify flow).

Few tests should be E2E tests (slow, expensive).

QA Phase: What Happens

Once your code is merged to develop, the QA team takes over:

Step 1: QA Deploys to Staging

QA deploys your feature to staging (production-like environment).

Staging = Production environment, but with test dataStep 2: QA Tests the Feature

QA walks through the acceptance criteria:

Feature: Export data as CSV

Acceptance Criteria:

☐ CSV file contains all user records → QA verifies

☐ CSV includes correct columns → QA checks file

☐ File is generated within 5 seconds → QA times it

☐ Users receive file download in browser → QA tests download

☐ File name includes timestamp → QA verifies

☐ Sensitive fields are excluded → QA checks CSV contentQA also tests:

✅ Edge cases (no data, special characters, very large exports)

✅ Error scenarios (permission denied, timeout, etc.)

✅ Browser compatibility

✅ Accessibility

✅ Performance

Step 3: QA Reports Findings

If QA finds issues:

QA: "On Chrome, the download button doesn't appear.

FireFox works fine. Mobile Safari shows error."

Developer: "I'll investigate the browser compatibility."The developer fixes the issue, commits, pushes, and the code goes back to QA.

If QA finds everything works:

QA: "Testing complete. All acceptance criteria verified.

No bugs found. ✅ APPROVED FOR PRODUCTION"Definition of Done

At this point, the feature is Done. What does that mean?

✅ Code written

✅ Unit tests written and passing

✅ Integration tests written and passing

✅ Code reviewed and approved

✅ Merged to develop

✅ QA tested in staging

✅ All acceptance criteria verified

✅ Edge cases handled

✅ Error scenarios handled

✅ Performance acceptable

✅ Documentation updated (if needed)

✅ Ready for productionA story that meets all of these is Done. A story that has some but not all of these is Not Done.

Teams that care about quality enforce a strict Definition of Done. Teams that skip steps have more production bugs.

🚀 Part 8: Pre-Production and Production Deployment - Getting to Real Users

The sprint is ending. Your feature is tested. Now it goes to production.

This is the most critical phase. A mistake here affects real users.

What Comes Before Production

Before deploying to production, most teams deploy to pre-production (or staging) first.

Development branch (develop)

↓

Staging environment

↓

Pre-production environment

↓

Production environmentDevelop → Staging: Continuous (every merge)

Staging → Pre-production: Manual (selected features ready)

Pre-production → Production: Manual (last verification)

Pre-Production Phase

Pre-production is production-like, but with:

✅ Real data (or realistic test data) ✅ Production configuration ✅ Real external services (real API keys, real database) ✅ But not affecting real users

The team does final verification:

On Pre-production:

Checklist before production:

☐ All acceptance criteria verified

☐ Tested with real data patterns

☐ Performance is acceptable (page loads < 2 seconds)

☐ Error messages are helpful

☐ No security issues found

☐ Data integrity is maintained

☐ Backward compatibility verified (didn't break existing features)

☐ All dependencies deployed correctly

☐ Monitoring/alerting configured

☐ Rollback plan documentedIf everything looks good: “Approved for production.”

If something is wrong: Stop. Fix it. Re-test.

Production Deployment: The Process

Production deployment should be automated and safe.

Most teams use continuous deployment or continuous delivery:

Approach 1: Continuous Deployment

Every merge to main (or release branch) automatically deploys to production.

Developer: Merge PR to main

↓

Automated tests run (10 minutes)

↓

If tests pass: Automatically deploy to production

↓

If tests fail: Deployment halts, developer notifiedThis is fast and keeps deployments small.

Approach 2: Continuous Delivery

Every merge is tested and ready for production, but deployment is manual:

Developer: Merge PR to main

↓

Automated tests run

↓

If tests pass: Create release candidate (ready to deploy)

↓

Team lead: Click "Deploy to Production" button

↓

Deployment happensThis gives the team control over when things go live.

The Deployment Window

Deployment usually happens:

Weekday mornings (9 AM - 12 PM) when team is awake and alert

Not after 3 PM (if something breaks, no one to help)

Not on Friday afternoon (too late to fix if issues)

Not on weekends or holidaysWhy?

✅ Team is available if something breaks

✅ Can rollback immediately

✅ Can monitor carefully

✅ Production issues have quick response time

Deployment Steps

When you deploy:

Step 1: Final checks

- Are all tests passing?

- Is monitoring set up?

- Is rollback plan ready?

Step 2: Deploy to production

- Use deployment tool (automated script)

- Database migrations run (if needed)

- New code deployed

- Application restarts

Step 3: Verify deployment

- Check application is running

- Verify critical features work

- Check error logs (any errors?)

- Monitor performance metrics

Step 4: Monitor next 24 hours

- Watch metrics closely

- Check error rates

- Read user feedback

- Be ready to rollback if neededIf Something Goes Wrong

If deployment breaks things:

Option 1: Quick fix

Issue is minor, fix is simple

Developer: Fix code → Merge → Deploy again (30 min)

Option 2: Rollback

Issue is major, uncertain how to fix

Deployment: Revert to previous version (5 min)

Rollback must be instant, automatedRollback is important: Every team should be able to rollback in < 5 minutes.

If rollback takes 2 hours, the team is doing it wrong.

Monitoring After Deployment

After deployment, the team watches carefully:

First 5 minutes:

- Is the app even running?

- Any obvious errors?

- Is performance OK?

First 30 minutes:

- Have users reported any issues?

- Are error rates elevated?

- Are specific features failing?

- Is database performance OK?

First 4 hours:

- Has behavior stabilized?

- Are there patterns in errors?

- Is rollback necessary?

After 24 hours:

- Is everything normal?

- No degradation in overall system health?

- Can we consider it "stable"?During this monitoring period, someone is on call. They respond immediately if there’s an issue.

Communication During Deployment

The team communicates deployment status:

9:00 AM: "Deploying to production"

9:05 AM: "Database migration completed"

9:07 AM: "Application restarted, verifying..."

9:10 AM: "Deployment successful ✅

All tests passing.

Monitoring performance.

No issues detected."

If problem: "Issue detected at 9:12 AM.

Initiating rollback."

9:14 AM: "Rollback complete. System restored.

Investigating root cause."This communication is in a Slack channel, visible to the whole team.

🎬 Part 9: Sprint Review / Demo - Showing What You Built

The sprint is ending. Your feature is live in production. Now the team celebrates.

The Sprint Review (also called Sprint Demo) happens at the end of every sprint.

When: Last day of sprint, typically 1-2 PM (after lunch, when people are back)

Duration: 1 hour (proportional to sprint length)

Who: Entire team, Product Owner, stakeholders, sometimes customers

Purpose: Show what was built. Get feedback. Celebrate.

What the Review Is NOT

Before I explain what it is, let me clarify what it’s not:

❌ NOT a Status Report

Don’t do this:

Developer: "I worked on export CSV feature.

It took me 8 story points and is now live.

Next week I'll work on rate limiting."This is boring and useless.

❌ NOT a Technical Deep-Dive

Don’t do this:

Developer: "The CSV generation uses CsvHelper library.

We create a DataTable, populate it with data,

then use the DataTable to write to a MemoryStream..."No one cares about implementation details.

❌ NOT a Lecture

The reviewers are not a passive audience sitting and listening.

What the Review IS

The Sprint Review is: “Here’s what we built. What do you think? Does it meet your needs?”

How It Works

Step 1: Product Owner Sets Context

The PO opens the meeting:

PO: "This sprint we focused on user data export and API security.

We delivered three features. Let me turn it over to the team to show you."The PO provides context, not details.

Step 2: Each Story Gets a Demo

For each story that was completed, the team demonstrates it working:

Developer: "We built the export CSV feature.

Let me show you how it works..."

[Developer logs into the app]

[Clicks "Export Data" button]

[File downloads]

[Opens the file in Excel to show format]

Developer: "The feature exports user records to CSV.

Users can download immediately for small exports,

and we email them a link for large exports.

It's live now, and working well."

PO: "Great. This is exactly what we wanted."Key: Show, don’t tell. Let the feature speak for itself.

Step 3: Stakeholders React and Ask Questions

After each demo:

Stakeholder 1: "Can users export this in other formats? Excel, PDF?"

Developer: "Not in this sprint. We built CSV.

If you want other formats, we can add them next sprint."

Stakeholder 2: "How long does it take for a large export?"

Developer: "Large exports (>50k records) go to background jobs.

Users get an email when it's ready, usually within 5 minutes."

Stakeholder 3: "Who can see this export? Is it private?"

Developer: "Users can only export their own data.

The system validates that they own the data before exporting."These are good questions. The team answers honestly.

Step 4: What Did NOT Get Done

The PO also mentions stories that were not completed:

PO: "We also started the admin dashboard feature.

We got the user dashboard done (which was 8 points of the 13 total).

The admin features (5 points) will be in next sprint.

This is intentional - we found the user dashboard was more valuable

and wanted to get it out first."This is important. Teams should be honest about what didn’t make the sprint.

Step 5: Gather Feedback

At the end:

PO: "So we built three features this sprint.

Does this match what you needed?

Any feedback or direction for next sprint?"

Stakeholders share feedback:

- What worked well

- What was unexpected

- Priorities for next sprint

- Blockers they're aware ofThis feedback is crucial. The team takes notes.

The Tone of Sprint Review

The Sprint Review should feel like:

✅ Celebration - “We did good work!”

✅ Transparency - “Here’s what we completed and what we didn’t”

✅ Collaboration - “What do you think? How are we doing?”

✅ Honesty - “This part works great, this part needs improvement”

It should NOT feel like:

❌ Status report to a boss

❌ Defensive (proving you worked hard)

❌ Pressure (worrying about judgment)

❌ Theatre (pretending things work when they don’t)

Teams that feel safe at Sprint Review get honest feedback. Teams that feel judged hide problems.

After Sprint Review

After the review, the team usually has:

1. Feedback from stakeholders

2. Confirmed priorities for next sprint

3. Adjusted backlog (based on new information)

4. Clear direction moving forwardThis directly feeds into the next sprint planning.

🔄 Part 10: Sprint Retrospective - Learning and Improving

The review is about what you built. The retrospective is about how you worked.

When: End of sprint, usually next day (after sprint review)

Duration: 1-1.5 hours

Who: Development team only (not stakeholders, not Product Owner usually)

Purpose: Reflect on what’s working, what’s not, and improve next sprint

The retrospective is the most important ceremony. It’s where the team gets better.

What the Retro Is NOT

❌ NOT a Complain Session

Don’t do this:

Developer 1: "The builds are slow!"

Developer 2: "I hate the database!"

Developer 3: "Meetings take too long!"

[Everyone leaves feeling worse]Complaining without solutions is toxic.

❌ NOT Management Review

The Scrum Master doesn’t judge the team. The team judges themselves.

❌ NOT Just Celebration

Some teams only discuss what went well. That’s nice, but doesn’t drive improvement.

What the Retro IS

The retro is: “What can we do better next sprint to be more productive, happier, and higher quality?”

How It Works

Step 1: Set a Safe Space

The Scrum Master opens:

Scrum Master: "In this retro, we're going to be honest about what's working

and what's not. No blame. No judgment. Just ideas for improvement.

Everything said here stays here. Let's be real with each other."This is crucial. Developers need to feel safe.

Step 2: What Went Well

The team reflects on positives:

Scrum Master: "What went well this sprint?"

Developer 1: "Code review process was really helpful.

The comments were constructive and I learned a lot."

Developer 2: "Daily standups were short and focused.

We stayed aligned the whole sprint."

Developer 3: "The testing framework change made tests faster to write."

Dev Lead: "Team really helped each other. When someone was stuck,

others jumped in. That felt good."Why start with positives?

✅ Sets positive tone

✅ Reminds team of what they’re doing right

✅ Builds on strengths

✅ Motivates the team

Step 3: What Didn’t Go Well

Now the honest part:

Scrum Master: "What didn't go well? What frustrated you?"

Developer 1: "The API endpoint took forever to test.

We should mock external dependencies."

Developer 2: "Code review took too long.

Some PRs sat for 3 days waiting for feedback."

Developer 3: "The database was slow. We spent 4 hours debugging

a query that could have been fixed with an index."

Dev Lead: "We had too many interruptions mid-sprint.

It's hard to focus on a story when you're answering support questions."Key: Be specific. Not “everything was bad,” but “this specific thing was hard.”

Step 4: Root Cause Discussion

For each issue, dig deeper:

Scrum Master: "You mentioned code review took too long.

Why did PRs sit for 3 days?"

Developer 2: "No one was reviewing. People were busy with their own stories.

And when someone did review, feedback came slowly because of timezone differences."

Team: "Ah, so it's:

1) No explicit review responsibility (everyone assumes someone else will)

2) Timezone issues (our team is distributed)

3) People prioritize their own work over reviews"Understanding root cause is essential.

Step 5: Propose Improvements

Now the team proposes solutions:

For slow code review:

Option 1: Assign review responsibility

"Every developer is responsible for reviewing one PR per day minimum"

Option 2: Use pair review

"Two developers review together in real-time (15 min zoom call)"

Option 3: Use review rotations

"Monday: Person A is on review duty. Tuesday: Person B. Etc."

Option 4: Set SLA

"All PRs should be reviewed within 4 hours during working hours"

Team decides: "Let's try the rotation approach.

One person is on review duty each day. They drop their own work to review."Not all ideas are good. The team picks the ones that are actionable, specific, and worth trying.

Step 6: Commit to Changes

Finally, the team commits:

Scrum Master: "So for next sprint, we're trying:

1. Review rotation (Person A on review duty each day)

2. Database index on the slow query

3. Assign a "support on-call" person (one dev handles interrupts)

4. Pair programming for complex features

Everyone OK with this?"

Team: "Yeah, let's try it."

Scrum Master: "Great. We'll check in on these at the next retro."These are written down and tracked.

The Retrospective Cycle

Retros compound over time:

Sprint 1 Retro:

"We need better code review process"

→ Implement review rotation

Sprint 2 Retro:

"Review rotation worked! PRs reviewed in <4 hours now"

→ Keep it

→ Identify next issue: "Testing is slow"

→ Plan improvement

Sprint 3 Retro:

"Testing is better. But now we're blocked on deployments"

→ Fix deployments

→ Continue cycleOver time, the team compounds small improvements. After 6 months, the team is 100% more effective than when they started.

Anti-Patterns in Retros

❌ Same Suggestions Every Retro

Sprint 1: "We need better testing"

Sprint 2: "We need better testing"

Sprint 3: "We need better testing"

[Nothing ever changes]If you keep suggesting the same thing, either implement it or stop suggesting it.

❌ Suggestions That Require Others

Developer: "We need QA to review features faster"

Scrum Master: "But QA isn't here. What can WE change?"Focus on what the development team can control.

❌ No Follow-up

Sprint 1 Retro: "We'll use pair programming for complex features"

Sprint 2 Retro: [No one mentions it, it never happened]

Sprint 2 Retro: [New suggestion about something else]At the start of each retro, check on previous commitments.

Scrum Master: "Last sprint we committed to pair programming.

How did that go?"

Developer: "We did it on the hard story, and it saved us 2 days.

The code quality was better too."

Scrum Master: "Great, keep doing that."🔗 Part 11: The Complete Cycle - How It All Connects

Now let’s step back and see the complete rhythm of a sprint.

The Two-Week Sprint Cycle (Typical)

WEEK 1

======

Monday 9 AM

- Sprint Planning (2 hours)

Input: Prioritized backlog

Output: Sprint backlog with committed stories

Monday-Friday (Every morning 10 AM)

- Daily Standup (15 minutes)

Sync on progress, identify blockers

Monday-Friday (Throughout day)

- Development

Writing code, creating PRs, code review

Friday 4 PM

- Mid-sprint check-in (optional, 15 min)

Any major issues? Do we need to adjust?

WEEK 2

======

Monday-Wednesday

- Development continues

Finishing stories, final testing

Wednesday 2 PM

- Pre-release testing begins

QA testing on staging

Thursday 10 AM

- Sprint Review (1 hour)

Demo features, get feedback

Thursday 11 AM

- Sprint Retrospective (1 hour)

Reflect on process, identify improvements

Thursday-Friday

- Deployment to production

With QA verification, monitoring

Friday 4 PM

- Sprint completeStory Lifecycle in the Sprint

Let’s follow a single story through the complete cycle:

Day 1 (Monday): Story Arrives

→ Backlog refinement already done

→ Sprint planning selects story

→ Story assigned to developer

Day 2-3 (Tuesday-Wednesday): Development

→ Developer creates feature branch

→ Implements feature with tests

→ Commits regularly

Day 4 (Thursday): Code Review

→ PR created

→ 2 developers review

→ Feedback, changes, approval

→ Merged to develop

Day 5-7 (Friday-Monday): QA Testing

→ Deployed to staging

→ QA tests all acceptance criteria

→ Tests edge cases, browsers, performance

→ Either approved or sent back to developer

Day 8-10 (Tuesday-Thursday): Final Preparation

→ Deployed to pre-production

→ Final verification

→ Deployment scheduled

Day 11 (Friday): Production

→ Deployed to production

→ Monitoring begins

→ After 24 hours, considered "stable"

Day 12 (Saturday+): Monitoring

→ Team watches for issues

→ If problem: quick fix or rollback

→ After 7 days: considered "proven"From day 1 (arrival) to day 12 (proven) is the complete lifecycle.

How Stories Flow

Not all stories finish in one sprint:

Sprint 1:

Story A: Arrive → Develop → Code review → Testing → Deploy ✅

Story B: Arrive → Develop → Code review → Not tested yet

Story C: Planned, but not enough capacity

Sprint 2:

Story B: Continue testing → Deploy ✅

Story C: Arrive → Develop → Code review → Not finished

Story D: Arrive → Develop

Sprint 3:

Story C: Finish → Testing → Deploy ✅

Story D: Continue testing

Story E: Arrive → DevelopThis is normal and healthy. Not all stories fit in one sprint.

Velocity: Measuring Progress

Over time, the team has a velocity - the number of story points they complete per sprint.

Sprint 1: 24 points

Sprint 2: 28 points

Sprint 3: 32 points

Sprint 4: 27 points (someone was sick)

Sprint 5: 31 points

Sprint 6: 30 points

Average velocity: ~30 points per sprintVelocity helps predict:

- How much can we commit next sprint?

- When will feature X be done?

- How many sprints to release?

Teams that track velocity can forecast reliably.

The Backlog Evolves

The backlog is not static. It evolves:

Sprint Planning Week 1:

Top 10 stories ready

Refined and estimated

Team selects 7 for sprint

During Sprint:

New requests arrive

PO prioritizes them

Refines top 5 for next sprint

Sprint Planning Week 2:

New top 10 ready

Includes new requests + old backlog

Team selects next batchThe backlog is continuously refined, not all at once.

🏆 Conclusion: From Process to Rhythm

I’ve walked you through the ideal Scrum and Agile workflow in exhaustive detail. From the moment a story arrives until it’s proven in production, 12+ days of ceremony, communication, and craftsmanship.

You might be thinking: “This seems like a lot.”

It is.

But here’s the truth: These practices exist because they work.

What This Rhythm Buys You

If you follow this workflow:

✅ Predictability - You know how much you’ll ship each sprint

✅ Quality - Code reviewed, tested, verified before production

✅ Safety - Easy to rollback if something breaks

✅ Happiness - Team is aligned, not chaotic

✅ Transparency - Everyone knows what’s happening

✅ Learning - Retros make the team better each sprint

✅ Speed - Counterintuitively, following process is faster than chaos

What Kills This Rhythm

Teams fail when they:

❌ Skip ceremonies - “We don’t have time for standups”

❌ Bypass code review - “This is too simple to review”

❌ Ignore testing - “QA can find bugs later”

❌ Skip retros - “We don’t have time for reflection”

❌ Change processes mid-sprint - “We need to pivot”

❌ Add people mid-sprint - “We’re behind, hire more”

❌ Treat stories as fixed - “We must finish everything”

These shortcuts feel fast at first. They crash hard later.

The Developer’s Mindset

As a developer, your job is not just to code. It’s to:

✅ Understand the business need - Not just implement features

✅ Communicate clearly - In standups, retros, code review

✅ Take responsibility - For quality, not just speed

✅ Help your team - Code review others, mentor juniors

✅ Reflect and improve - Retros are for learning

✅ Deliver safely - Through testing, review, QA

✅ Own the rhythm - Make ceremonies effective

Developers who master this rhythm become senior developers. Developers who just code become stuck.

Building Your Own Rhythm

Not all teams need exactly this process. But all teams need:

- Regular planning - Knowing what to work on

- Daily sync - Staying aligned

- Code review - Learning and quality

- Testing - Confidence in code

- Regular reflection - Getting better

- Celebration - Acknowledging progress

Start with these. Adapt as you learn.

Final Thought

Scrum is not the goal. Shipping great software consistently is the goal.

Scrum is just a framework that helps you do that.

When you feel the rhythm - the daily standups that sync the team, the retros that identify improvements, the demos that show progress - you’ll understand why these practices matter.

It’s not about following rules. It’s about building a team that works together effectively, ships with confidence, and continuously improves.

That’s the ideal Scrum workflow.

Welcome to it.

fin.

Tags

Related Articles

Design Patterns: The Shared Vocabulary of Software

A comprehensive guide to design patterns explained in human language: what they are, when to use them, how to implement them, and why they matter for your team and your business.

Clean Architecture: Building Software that Endures

A comprehensive guide to Clean Architecture explained in human language: what each layer is, how they integrate, when to use them, and why it matters for your business.

GitFlow + GitOps: The Complete Senior Git Guide for Agile Teams and Scrum

A comprehensive tutorial on GitFlow and GitOps best practices from a senior developer's perspective. Master branch strategy, conflict resolution, commit discipline, merge strategies, documentation, and how to be a Git professional in Agile/Scrum teams.