Concurrency vs Parallelism: Understanding the Paradigm That Powers Modern Software

A deep exploration of concurrent and parallel programming: what they are, how they differ, common pitfalls, real-time considerations, and the mental models needed to build robust modern systems.

Few topics in software engineering generate as much confusion as the distinction between concurrency and parallelism. Developers use the terms interchangeably, technical interviews test for definitions that miss the point, and production systems fail because teams conflate the two concepts.

This confusion is not merely academic. The difference between concurrency and parallelism affects how you design systems, how you debug failures, and whether your application survives its first encounter with real-world load. Understanding this distinction deeply changes how you think about software architecture.

This article explores the fundamental nature of concurrent and parallel programming. We will examine what each concept actually means, why the distinction matters, how to think about problems in each paradigm, and what pitfalls await the unwary. We will also venture into related territory: real-time systems, reactive programming, and the broader landscape of execution models that define modern software.

No code. No framework-specific advice. Just the mental models you need to reason about these concepts correctly.

The Fundamental Distinction

Let us start with the clearest possible definitions.

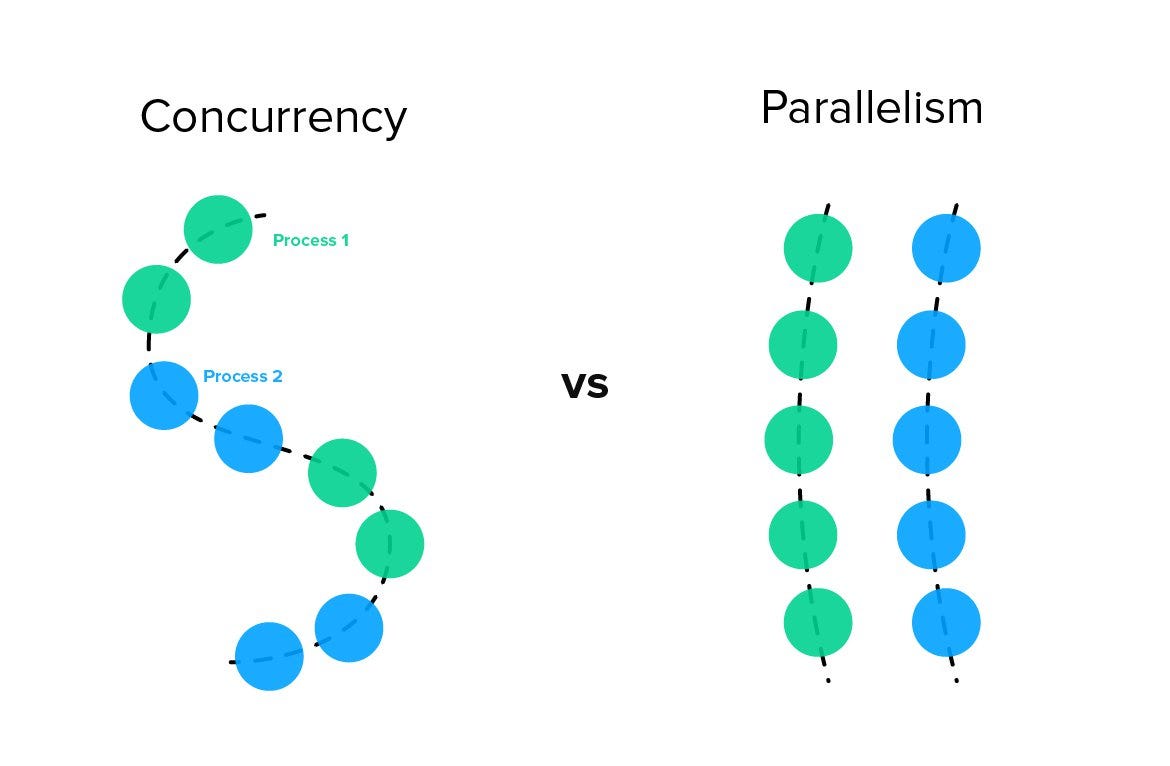

Concurrency is about dealing with multiple things at once. It is a property of how a program is structured. A concurrent program has multiple logical threads of control that can make progress independently. Whether these threads actually execute simultaneously is irrelevant to whether the program is concurrent.

Parallelism is about doing multiple things at once. It is a property of how a program executes. A parallel program actually performs multiple computations at the same moment in time, typically using multiple CPU cores or multiple machines.

The key insight: concurrency is about structure; parallelism is about execution.

A single-core processor can run a concurrent program by switching between tasks rapidly. The tasks make progress interleaved in time, but never truly simultaneously. A multi-core processor can run a parallel program where tasks genuinely execute at the same instant.

You can have concurrency without parallelism. You can have parallelism without concurrency. You can have both. You can have neither. These are independent concepts that happen to interact in interesting ways.

Visual Representation: The Four Quadrants

quadrantChart

title Concurrency vs Parallelism Matrix

x-axis "No Parallelism" --> "Parallelism"

y-axis "No Concurrency" --> "Concurrency"

quadrant-1 "Concurrent + Parallel"

quadrant-2 "Concurrent Only"

quadrant-3 "Neither"

quadrant-4 "Parallel Only"

"Web Server (multi-core)": [0.85, 0.85]

"Event Loop (single-core)": [0.15, 0.80]

"Simple Script": [0.15, 0.15]

"SIMD Operations": [0.85, 0.20]

"Async I/O": [0.25, 0.75]

"GPU Compute": [0.90, 0.30]Timeline Comparison

The following diagram illustrates how three tasks execute under different models:

gantt

title Sequential vs Concurrent vs Parallel Execution

dateFormat X

axisFormat %s

section Sequential

Task A :a1, 0, 3

Task B :a2, after a1, 3

Task C :a3, after a2, 3

section Concurrent (1 core)

Task A-1 :b1, 0, 1

Task B-1 :b2, 1, 1

Task C-1 :b3, 2, 1

Task A-2 :b4, 3, 1

Task B-2 :b5, 4, 1

Task C-2 :b6, 5, 1

Task A-3 :b7, 6, 1

Task B-3 :b8, 7, 1

Task C-3 :b9, 8, 1

section Parallel (3 cores)

Task A :c1, 0, 3

Task B :c2, 0, 3

Task C :c3, 0, 3Why the Confusion Persists

The confusion between concurrency and parallelism persists for several reasons.

First, the same mechanisms often enable both. Threads, for instance, can be used to structure a concurrent program or to achieve parallel execution. The tool looks the same even when the purpose differs.

Second, concurrent programs often run in parallel on modern hardware. When you write a concurrent program today, it probably executes on multiple cores. This makes it easy to conflate the structural choice (concurrency) with the execution reality (parallelism).

Third, many problems benefit from both. A web server handling multiple requests is concurrent in structure and often parallel in execution. The two concepts blend together in practice even though they remain distinct in principle.

Fourth, the terminology varies across communities. Some languages and frameworks use “concurrent” when they mean “parallel” and vice versa. Documentation and tutorials perpetuate imprecise language.

Understanding requires separating these concepts deliberately, even when they appear together in practice.

The Restaurant Analogy

Analogies can clarify the distinction. Consider a restaurant kitchen.

Sequential execution: One chef prepares one dish at a time. The chef finishes the appetizer completely before starting the main course. Simple but slow.

Concurrent execution: One chef works on multiple dishes by interleaving tasks. While the pasta water heats, the chef chops vegetables. While the sauce simmers, the chef plates the appetizer. The chef handles multiple dishes but only has two hands. Progress on multiple things, but not simultaneously.

Parallel execution: Multiple chefs each work on a different dish at the same time. Three dishes actually cook simultaneously because three people work simultaneously. More throughput through actual simultaneity.

Concurrent and parallel: Multiple chefs, each interleaving work on multiple dishes. The kitchen handles many orders through both task-switching and multiple workers.

The concurrent chef is dealing with multiple dishes. The parallel kitchen is doing multiple dishes. The distinction maps directly to the programming concepts.

Kitchen Execution Flow Diagram

flowchart TB

subgraph Sequential["Sequential Execution"]

direction LR

S1[Dish A] --> S2[Dish B] --> S3[Dish C]

end

subgraph Concurrent["Concurrent Execution (1 Chef)"]

direction TB

C1["Time 1: Start Dish A"]

C2["Time 2: Switch to Dish B"]

C3["Time 3: Switch to Dish C"]

C4["Time 4: Continue Dish A"]

C5["Time 5: Continue Dish B"]

C1 --> C2 --> C3 --> C4 --> C5

end

subgraph Parallel["Parallel Execution (3 Chefs)"]

direction LR

P1["Chef 1: Dish A"]

P2["Chef 2: Dish B"]

P3["Chef 3: Dish C"]

endConcurrency: Managing Complexity

Concurrency is fundamentally about managing complexity. When a program must handle multiple independent concerns, concurrency provides a way to structure that program so each concern can be reasoned about separately.

Consider a desktop application that must:

- Respond to user input

- Fetch data from a network

- Update the display

- Save files to disk

- Check for updates

Without concurrency, the program must interleave all these concerns in a single flow of control. The code for handling user input gets mixed with network code, display code, file code, and update code. The result is spaghetti: tangled, difficult to understand, impossible to modify safely.

With concurrency, each concern becomes a separate logical thread of control. User input handling runs as its own thread of execution. Network operations run as their own thread. Display updates run as their own thread. The code for each concern is isolated and comprehensible.

This is concurrency as a design principle. The goal is not performance but clarity. The goal is not speed but sanity. Concurrent structure makes complex programs manageable.

The Benefits of Concurrent Structure

Modularity: Each concurrent component can be developed, tested, and debugged independently. Changes to network handling do not affect user input handling because they exist in separate threads of control.

Responsiveness: A concurrent program can remain responsive to user input even while performing long operations. The user input thread continues running while the network thread waits for data.

Natural modeling: Many real-world problems involve multiple independent entities operating simultaneously. Concurrent structure maps naturally to these problems. A chat application models each conversation as a separate thread of control because that matches reality.

Simplified reasoning: Within each thread of control, reasoning is sequential. You can think about what happens step by step without considering what other parts of the program are doing at each moment.

The Costs of Concurrent Structure

Coordination complexity: Independent threads must sometimes coordinate. One thread produces data another thread consumes. One thread must wait for another to complete. This coordination introduces complexity that sequential programs avoid.

Non-determinism: Concurrent programs can behave differently on different runs depending on how threads interleave. This makes debugging harder because bugs may not reproduce reliably.

Shared state hazards: When multiple threads access the same data, subtle bugs emerge. These bugs are notoriously difficult to find and fix.

Concurrency is a tool for managing complexity, but it introduces its own complexity. The art is knowing when the benefits outweigh the costs.

Parallelism: Achieving Performance

Parallelism is fundamentally about performance. When a computation can be divided into independent parts, parallelism allows those parts to execute simultaneously, completing the total work faster.

Consider processing a million images. Each image is independent: the processing of one does not affect the processing of another. On a single core, processing takes a certain time. On eight cores, processing can take roughly one-eighth the time if the work divides evenly.

This is parallelism as an execution strategy. The goal is speed. The goal is throughput. Parallel execution harnesses multiple processors to complete work faster than sequential execution could.

The Benefits of Parallel Execution

Speed: The primary benefit is raw speed. Computationally intensive work completes faster when divided across multiple processors.

Scalability: Parallel programs can take advantage of additional hardware. As more cores become available, more work can happen simultaneously.

Efficiency: Modern processors spend much of their time idle during I/O operations. Parallel execution can keep more processors busy more of the time.

The Costs of Parallel Execution

Overhead: Dividing work and combining results takes time. If the work is small, the overhead of parallelization exceeds the benefit.

Amdahl’s Law: Every program has portions that cannot be parallelized. These sequential portions limit the maximum speedup regardless of how many processors you add.

Synchronization costs: When parallel threads must coordinate, they often wait for each other. This waiting reduces the effective parallelism.

Complexity: Parallel programs must divide work, distribute it to processors, and combine results. This machinery adds complexity to the program.

Parallelism is a tool for achieving performance, but it has limits and costs. The art is knowing when parallelism will actually help and when it will just add complexity.

The Interplay of Concurrency and Parallelism

While concurrency and parallelism are distinct concepts, they interact in important ways.

Concurrency enables parallelism: A concurrent program structure makes parallel execution possible. If your program has only one thread of control, there is nothing to run in parallel. Concurrent structure creates the possibility of parallel execution.

Parallelism rewards concurrency: On multi-core hardware, a concurrent program can execute in parallel without modification. The concurrent structure that was designed for clarity automatically benefits from multiple processors.

Neither requires the other: A concurrent program can run on a single core with no parallelism. A parallel program can have a simple non-concurrent structure that happens to run on multiple cores.

The most powerful combination is a program with concurrent structure running with parallel execution. The concurrent structure provides modularity and responsiveness. The parallel execution provides performance.

Common Pitfalls and Problems

Working with concurrency and parallelism introduces categories of problems that do not exist in sequential programming. Understanding these problems is essential for building reliable systems.

Race Conditions

A race condition occurs when the behavior of a program depends on the relative timing of events in different threads. The “race” is between threads to access shared resources, and the outcome depends on who wins.

Consider two threads incrementing a counter. Each thread reads the current value, adds one, and writes the result. If both threads read the same initial value, both compute the same incremented value, and both write the same result. One increment is lost.

sequenceDiagram

participant Counter as Counter (value: 5)

participant A as Thread A

participant B as Thread B

Note over Counter,B: Race Condition Example

A->>Counter: Read value (gets 5)

B->>Counter: Read value (gets 5)

A->>A: Compute 5 + 1 = 6

B->>B: Compute 5 + 1 = 6

A->>Counter: Write 6

B->>Counter: Write 6

Note over Counter: Final value: 6 (should be 7!)This is a race condition. The program’s correctness depends on threads happening to execute in the right order. Sometimes it works. Sometimes it fails. The failure is intermittent and difficult to reproduce.

Race conditions are insidious because they can lurk in code for years before manifesting. The timing that triggers them may occur only under load, only on certain hardware, or only on days that end in ‘y’. Testing cannot reliably find them because they are not deterministic.

Deadlocks

A deadlock occurs when two or more threads wait for each other indefinitely. Thread A holds resource X and waits for resource Y. Thread B holds resource Y and waits for resource X. Neither can proceed. The system freezes.

flowchart LR

subgraph Deadlock["Deadlock Cycle"]

A[Thread A] -->|holds| X[Resource X]

A -->|waits for| Y[Resource Y]

B[Thread B] -->|holds| Y

B -->|waits for| X

end

style A fill:#ff6b6b,color:#fff

style B fill:#ff6b6b,color:#fff

style X fill:#4ecdc4,color:#fff

style Y fill:#4ecdc4,color:#fffDeadlocks require four conditions:

- Mutual exclusion: Resources cannot be shared

- Hold and wait: Threads hold resources while waiting for others

- No preemption: Resources cannot be forcibly taken

- Circular wait: A cycle of threads waiting for each other

Eliminating any condition prevents deadlock. The challenge is that eliminating conditions is often impractical or introduces other problems.

Livelocks

A livelock is similar to a deadlock except that the threads are not blocked. They are actively executing but making no progress. Each thread changes its state in response to the other, but the changes prevent either from completing.

stateDiagram-v2

[*] --> PersonA_Left

PersonA_Left --> PersonA_Right: B moves left

PersonA_Right --> PersonA_Left: B moves right

note right of PersonA_Left: Both keep moving

note right of PersonA_Right: No progress madeImagine two people meeting in a narrow hallway. Each steps aside to let the other pass. Both step to the same side. Both step to the other side. Both continue stepping back and forth indefinitely, being perfectly polite and making no progress.

Livelocks are harder to detect than deadlocks because the threads are running. CPU is consumed. Activity occurs. But nothing useful happens.

Starvation

Starvation occurs when a thread never gets access to resources it needs because other threads monopolize those resources. The starving thread is not blocked indefinitely like in a deadlock; it just never wins the competition for resources.

flowchart TB

subgraph Resource_Access["Resource Access Pattern"]

R[Shared Resource]

T1[Thread 1 - High Priority] -->|always wins| R

T2[Thread 2 - High Priority] -->|always wins| R

T3[Thread 3 - Low Priority] -.->|never gets access| R

end

style T3 fill:#ff9999,color:#000

style R fill:#4ecdc4,color:#fffA scheduling policy that always favors certain threads can cause starvation. Priority inversion, where a high-priority thread waits for a low-priority thread that cannot run because medium-priority threads consume all CPU, is a famous form of starvation.

Priority Inversion

Priority inversion occurs when a high-priority task is blocked waiting for a lower-priority task. If a low-priority thread holds a lock that a high-priority thread needs, the high-priority thread must wait. Meanwhile, medium-priority threads may run freely, effectively inverting the priorities.

The Mars Pathfinder mission famously suffered from priority inversion. The spacecraft’s computer would reset itself because a high-priority task could not complete in time. The root cause was priority inversion in the software.

Memory Visibility Issues

In modern computer architectures, each CPU core has its own cache. When one thread modifies a value, other threads may not see the modification immediately. They may continue reading a stale value from their own cache.

This is a memory visibility problem. The threads are not necessarily racing to access the value simultaneously. The problem is that modifications do not propagate between caches instantaneously.

Programming languages and hardware provide memory barriers and synchronization primitives to ensure visibility. Using them correctly requires understanding the memory model of your platform.

False Sharing

When multiple threads access different data that happens to reside on the same cache line, they interfere with each other even though they are not sharing data logically. Each thread’s writes invalidate the other threads’ caches, causing expensive cache synchronization.

This is false sharing. The performance impact can be severe: threads that should run independently instead contend on cache lines. The solution is ensuring that data accessed by different threads resides on different cache lines.

Synchronization Mechanisms

When concurrent or parallel threads must coordinate, they use synchronization mechanisms. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for working with concurrent systems.

Overview of Synchronization Primitives

flowchart TB

subgraph Primitives["Synchronization Mechanisms"]

direction TB

subgraph Blocking["Blocking Primitives"]

L[Mutex/Lock]

S[Semaphore]

M[Monitor]

RW[Read-Write Lock]

end

subgraph NonBlocking["Non-Blocking Approaches"]

LF[Lock-Free Structures]

A[Atomic Operations]

end

subgraph Communication["Message-Based"]

MP[Message Passing]

CH[Channels]

AC[Actor Model]

end

end

L --> |"1 thread"| Resource

S --> |"N threads"| Resource

RW --> |"Many readers OR 1 writer"| Resource

MP --> |"No shared state"| IsolationLocks and Mutexes

A lock or mutex (mutual exclusion) ensures that only one thread can access a resource at a time. A thread acquires the lock before accessing the resource and releases it afterward. Other threads attempting to acquire the lock must wait.

sequenceDiagram

participant T1 as Thread 1

participant Lock as Mutex

participant T2 as Thread 2

participant R as Resource

T1->>Lock: acquire()

Lock-->>T1: granted

T2->>Lock: acquire()

Note over T2,Lock: Thread 2 waits...

T1->>R: access resource

T1->>Lock: release()

Lock-->>T2: granted

T2->>R: access resource

T2->>Lock: release()Locks prevent race conditions by ensuring exclusive access. They also introduce the possibility of deadlocks if threads acquire multiple locks in different orders.

Semaphores

A semaphore generalizes a lock to allow a specific number of threads to access a resource simultaneously. A semaphore with a count of one behaves like a lock. A semaphore with a higher count allows that many threads to proceed concurrently.

Semaphores are useful for managing pools of resources, like database connections or thread pools.

Monitors

A monitor combines a lock with condition variables. The lock ensures exclusive access to shared data. The condition variables allow threads to wait for specific conditions and to signal when conditions change.

Monitors provide a higher-level abstraction than raw locks and condition variables, making correct synchronization easier to achieve.

Read-Write Locks

A read-write lock distinguishes between readers, who only observe data, and writers, who modify it. Multiple readers can hold the lock simultaneously because reading does not conflict with reading. Writers require exclusive access.

flowchart LR

subgraph Readers["Readers (can be concurrent)"]

R1[Reader 1]

R2[Reader 2]

R3[Reader 3]

end

subgraph Writer["Writer (exclusive)"]

W1[Writer]

end

RWL{Read-Write Lock}

R1 --> RWL

R2 --> RWL

R3 --> RWL

W1 --> RWL

RWL --> Data[(Shared Data)]

Note1[/"Multiple readers allowed"/]

Note2[/"Writer blocks all others"/]Read-write locks improve concurrency for read-heavy workloads. Multiple threads can read simultaneously, blocking only when a write occurs.

Lock-Free Data Structures

Lock-free data structures allow multiple threads to access shared data without traditional locking. They use atomic operations and clever algorithms to ensure correctness without blocking.

Lock-free structures avoid deadlock by design and often perform better under contention. They are also significantly harder to implement correctly.

Message Passing

Rather than sharing memory and synchronizing access, threads can communicate by passing messages. Each thread has its own private data. Communication occurs only through explicit message channels.

flowchart LR

subgraph Actor1["Actor A"]

A1[Private State A]

end

subgraph Actor2["Actor B"]

A2[Private State B]

end

subgraph Actor3["Actor C"]

A3[Private State C]

end

Actor1 -->|message| Actor2

Actor2 -->|message| Actor3

Actor3 -->|message| Actor1

Note["No shared mutable state"]Message passing eliminates many synchronization hazards by eliminating shared mutable state. It shifts the problem from “how do we safely share data” to “how do we structure communication.”

Reactive and Asynchronous Programming

Beyond traditional concurrency and parallelism lies a family of programming models focused on responsiveness and event handling.

Programming Models Comparison

flowchart TB

subgraph Sync["Synchronous (Blocking)"]

S1[Call Function] --> S2[Wait...] --> S3[Get Result]

end

subgraph Async["Asynchronous (Non-Blocking)"]

A1[Call Function] --> A2[Continue Working]

A3[Callback/Promise] --> A4[Handle Result]

A2 -.->|"later"| A3

end

subgraph Reactive["Reactive (Stream-Based)"]

R1[Data Stream] --> R2[Transform] --> R3[Filter] --> R4[Subscribe]

R1 -->|"continuous flow"| R2

endEvent-Driven Programming

Event-driven programming structures programs around events and handlers. The program waits for events: user input, network messages, timer expirations, file system changes. When an event occurs, the corresponding handler executes.

flowchart TB

EL[Event Loop]

subgraph Events["Event Queue"]

E1[Click Event]

E2[Network Response]

E3[Timer Event]

end

subgraph Handlers["Event Handlers"]

H1[onClick Handler]

H2[onResponse Handler]

H3[onTimeout Handler]

end

E1 --> EL

E2 --> EL

E3 --> EL

EL --> H1

EL --> H2

EL --> H3This model is inherently concurrent in structure. Multiple events can be pending. Multiple handlers can be ready to run. But the execution may or may not be parallel.

Event-driven programming dominates user interface development and network server design. It provides responsiveness and scales well for I/O-bound workloads.

Asynchronous Programming

Asynchronous programming allows operations to proceed without blocking the calling thread. Rather than waiting for an operation to complete, the caller continues immediately and handles the result later through callbacks, promises, or other mechanisms.

sequenceDiagram

participant App as Application

participant API as Async API

participant DB as Database

App->>API: fetchData() [non-blocking]

Note over App: Continues other work

App->>App: processLocalData()

App->>App: updateUI()

API->>DB: query

DB-->>API: result

API-->>App: Promise resolves

App->>App: handleData()Asynchronous programming enables concurrency without threads. A single thread can manage many concurrent operations by starting them asynchronously and handling completions as they arrive.

This model is particularly effective for I/O-bound workloads. While waiting for a network response, the thread can handle other operations rather than sitting idle.

Reactive Programming

Reactive programming extends asynchronous programming with streams of events and operators for transforming those streams. Data flows through a pipeline of transformations, with the system automatically propagating changes.

flowchart LR

Source[Data Source] --> Map[Map] --> Filter[Filter] --> Reduce[Reduce] --> Sub[Subscriber]

Source -->|"emit: 1,2,3,4,5"| Map

Map -->|"x => x*2: 2,4,6,8,10"| Filter

Filter -->|"x > 5: 6,8,10"| Reduce

Reduce -->|"sum: 24"| SubReactive programming is declarative rather than imperative. You describe the relationships between data streams rather than the sequence of operations. The runtime handles the execution details.

This model suits applications with complex event processing, real-time data feeds, and user interfaces that must react to many sources of change.

The Relationship to Concurrency

These programming models are all forms of concurrent structure. They enable programs to deal with multiple things at once. Whether they execute in parallel depends on the runtime and hardware.

The key insight is that concurrency can be achieved through mechanisms other than threads. Event loops, async/await, and reactive streams are all ways to structure concurrent programs. Each has different tradeoffs for different problem domains.

Real-Time Systems

Real-time systems add another dimension to concurrent and parallel programming: timing constraints. A real-time system must not only compute the correct result but must do so within a specified time.

Hard and Soft Real-Time

Hard real-time systems have absolute deadlines. Missing a deadline is a system failure. Aircraft flight control, medical device monitoring, and industrial process control are hard real-time systems. A late response is as bad as a wrong response.

Soft real-time systems have deadlines that should be met but can be missed occasionally without catastrophe. Video playback, audio processing, and interactive applications are soft real-time. Occasional missed deadlines cause degraded quality, not failures.

flowchart TB

subgraph Hard["Hard Real-Time"]

H1[Task Execution]

HD[Deadline]

HF[FAILURE if missed]

H1 --> HD

HD -->|missed| HF

end

subgraph Soft["Soft Real-Time"]

S1[Task Execution]

SD[Deadline]

SQ[Quality Degradation]

S1 --> SD

SD -->|missed| SQ

end

Examples1["Examples: Flight Control, Pacemaker, ABS Brakes"]

Examples2["Examples: Video Streaming, Games, UI"]

Hard --- Examples1

Soft --- Examples2

style HF fill:#ff4444,color:#fff

style SQ fill:#ffaa00,color:#000The Challenge of Real-Time

Real-time requirements interact with concurrency in complex ways. Multiple concurrent tasks compete for CPU time. Ensuring that high-priority tasks meet their deadlines while lower-priority tasks also complete requires careful scheduling.

gantt

title Real-Time Task Scheduling

dateFormat X

axisFormat %s

section High Priority

Critical Task :crit, h1, 0, 2

Critical Task 2 :crit, h2, 5, 2

section Medium Priority

Regular Task A :m1, 2, 2

Regular Task B :m2, 7, 2

section Low Priority

Background Work :l1, 4, 1

Background Work :l2, 9, 1

section Deadlines

Deadline 1 :milestone, d1, 3, 0

Deadline 2 :milestone, d2, 8, 0Real-time systems must analyze worst-case execution time, not average time. Every path through the code, every synchronization point, every memory allocation must be bounded. Garbage collection pauses, lock contention, and I/O delays all threaten deadlines.

Parallel execution helps real-time systems by providing more compute capacity. But parallelism also introduces synchronization overhead and non-determinism that can threaten deadlines. The tradeoffs are complex.

Determinism

Real-time systems demand determinism: the same inputs must produce the same behavior in the same time. Non-determinism from thread scheduling, garbage collection, or cache behavior makes timing analysis impossible.

Achieving determinism often requires giving up conveniences that non-real-time programmers take for granted. Dynamic memory allocation, recursion, and complex synchronization patterns may be forbidden in hard real-time code.

Distributed Systems and Concurrency

When systems span multiple machines, concurrency becomes distributed concurrency. The challenges multiply.

flowchart TB

subgraph Distributed["Distributed System"]

N1[Node 1]

N2[Node 2]

N3[Node 3]

N1 <-->|"messages"| N2

N2 <-->|"messages"| N3

N1 <-->|"messages"| N3

end

subgraph Challenges["Challenges"]

C1[Network Latency]

C2[Partial Failures]

C3[Message Ordering]

C4[Clock Skew]

end

Distributed --- ChallengesNetwork Partitions

In a distributed system, machines can lose contact with each other due to network failures. Some machines can communicate while others cannot. The system must continue operating despite this partial connectivity.

flowchart TB

subgraph Partition["Network Partition"]

subgraph GroupA["Partition A"]

N1[Node 1]

N2[Node 2]

end

subgraph GroupB["Partition B"]

N3[Node 3]

N4[Node 4]

end

N1 <--> N2

N3 <--> N4

N1 x--x N3

N2 x--x N4

end

style N1 fill:#4ecdc4,color:#fff

style N2 fill:#4ecdc4,color:#fff

style N3 fill:#ff6b6b,color:#fff

style N4 fill:#ff6b6b,color:#fffConcurrency on a single machine assumes reliable communication between threads. Distributed concurrency cannot make this assumption. Messages may be lost, delayed, or delivered out of order.

Consistency Models

Distributed systems must choose consistency models that determine how updates propagate and what guarantees clients receive. Strong consistency ensures all clients see the same data but limits performance and availability. Weak consistency allows stale data but enables better performance and fault tolerance.

These choices interact with concurrency. A distributed system with many concurrent clients must reason about which updates they see and in what order.

The CAP Theorem

The CAP theorem states that a distributed system can provide at most two of three guarantees: Consistency, Availability, and Partition tolerance. Since network partitions are unavoidable, systems must choose between consistency and availability during partitions.

flowchart TB

CAP{{"CAP Theorem"}}

C[Consistency]

A[Availability]

P[Partition Tolerance]

CAP --> C

CAP --> A

CAP --> P

CP["CP Systems<br/>(e.g., HBase, MongoDB)"]

AP["AP Systems<br/>(e.g., Cassandra, DynamoDB)"]

CA["CA Systems<br/>(single node only)"]

C --> CP

P --> CP

A --> AP

P --> AP

C --> CA

A --> CA

Note["Pick any 2, but partitions<br/>are inevitable in distributed systems"]This fundamental tradeoff shapes the design of every distributed system. Understanding it is essential for designing systems that behave correctly under failure.

Consensus Algorithms

Distributed systems often need multiple machines to agree on a value or decision. Consensus algorithms solve this problem despite the possibility of failures and network issues.

Consensus is expensive. It requires multiple round-trips between machines and can block progress during failures. Systems that need consensus must use it sparingly.

Thinking About Concurrent Problems

How should you approach problems that involve concurrency or parallelism? Here are mental models that help.

Identify Independent Work

The first question for parallelism: what work is independent? Independent work can execute simultaneously without coordination. The more independent work exists, the more parallelism is possible.

Look for data that can be processed without depending on other data. Look for computations where each piece needs only local information. Look for embarrassingly parallel problems where the structure screams for parallel execution.

Identify Necessary Coordination

The first question for concurrency: what coordination is required? Where must threads wait for each other? Where must they exchange information? Where must they agree on shared state?

Coordination is expensive. Every point of coordination limits parallelism and introduces potential bugs. Minimize coordination by restructuring problems to increase independence.

Choose the Right Abstraction Level

Low-level primitives like locks and threads provide maximum control but require careful programming. High-level abstractions like actor systems and reactive streams provide safety but may not fit every problem.

Match the abstraction level to the problem. Simple problems with well-understood patterns can use higher-level abstractions. Complex problems with unusual requirements may need lower-level control.

Design for Failure

Concurrent and parallel systems fail in ways sequential systems do not. Threads deadlock. Messages are lost. Races corrupt data. Design assuming failure will occur.

Timeouts prevent indefinite waiting. Retries recover from transient failures. Circuit breakers prevent cascade failures. Supervision hierarchies restart failed components.

Test Under Load

Concurrency bugs often appear only under load. Race conditions that never manifest in single-threaded tests appear when many threads contend. Deadlocks that never form with light load emerge when the system is stressed.

Testing concurrent systems requires realistic load, varied timing, and enough runs to trigger probabilistic failures. Stress testing is not optional.

Use Static Analysis

Many concurrency bugs can be detected by static analysis tools. Race detectors find unsynchronized access to shared data. Deadlock detectors find potential lock cycles. Model checkers explore possible thread interleavings.

These tools catch bugs that testing misses. They are essential for serious concurrent programming.

When to Use What

Not every problem needs concurrency. Not every problem benefits from parallelism. Choosing the right approach requires understanding the problem domain.

Use Concurrency When

The problem involves multiple independent activities: User interfaces with background tasks. Servers handling multiple clients. Systems coordinating multiple subsystems. Concurrency provides natural structure for these problems.

Responsiveness matters: Long operations must not block user interaction. Network delays must not freeze the application. Concurrency keeps the system responsive by separating slow operations from interactive operations.

The problem models reality: Real-world systems involve many actors operating independently. Concurrent structure maps to this reality more naturally than sequential structure.

Use Parallelism When

Performance is limited by computation: CPU-bound workloads benefit from more CPUs. If the bottleneck is waiting for I/O, more CPUs do not help.

Work can be divided: Parallel execution requires divisible work. If everything depends on everything else, parallelism is not possible.

The scale justifies the complexity: Parallelism adds complexity. For small problems, sequential execution is simpler and fast enough. For large problems, the performance benefit justifies the complexity.

Avoid Both When

The problem is simple and sequential: Not everything needs concurrency. A script that processes files one at a time is simpler without concurrent structure. Simplicity has value.

The overhead exceeds the benefit: Very small tasks do not benefit from parallelism. The overhead of distributing and combining work exceeds any speedup. Sequential execution is faster for small work.

Correctness is paramount and complexity is dangerous: Safety-critical systems sometimes use sequential designs specifically because they are easier to analyze and verify. The performance cost may be acceptable to achieve higher confidence in correctness.

The Future of Concurrent and Parallel Programming

The landscape of concurrent and parallel programming continues to evolve.

Hardware trends: Processors are not getting faster; they are getting wider. More cores per chip, more chips per system. Software must use parallelism to access this performance.

Language support: Programming languages are providing better abstractions for concurrent and parallel programming. Memory safety, data race prevention, and structured concurrency are becoming language features rather than library patterns.

Async everywhere: Asynchronous programming is becoming the default for I/O-bound code. Languages that once treated async as an advanced feature now make it the primary programming model.

Actor systems and message passing: The actor model, which avoids shared state by using message passing between isolated actors, is gaining adoption. It provides safety guarantees that shared-memory concurrency cannot.

Verification tools: Static analysis, model checking, and formal verification are becoming more practical. Tools that once required PhD expertise are becoming accessible to working programmers.

The trend is toward safer abstractions that make concurrent and parallel programming less error-prone. The low-level primitives remain available for those who need them, but higher-level models provide correctness guarantees for those who can use them.

Conclusion

Concurrency and parallelism are distinct concepts that interact in complex ways. Concurrency is about structure: dealing with multiple things at once. Parallelism is about execution: doing multiple things at once. Understanding this distinction is fundamental to building correct and efficient systems.

Concurrent programming introduces new categories of bugs: race conditions, deadlocks, livelocks, and visibility issues. These bugs are subtle, intermittent, and difficult to reproduce. Avoiding them requires careful design, appropriate abstractions, and thorough testing.

Parallel programming offers performance benefits but requires divisible work and introduces overhead. Not every problem benefits from parallelism. Knowing when parallelism helps and when it just adds complexity is an essential skill.

Real-time systems add timing constraints that interact with concurrency in challenging ways. Distributed systems add network unreliability that transforms every concurrency problem into a harder version of itself.

The mental models matter more than the specific mechanisms. Understanding why concurrency bugs occur is more valuable than memorizing which lock to use. Understanding when parallelism helps is more valuable than knowing the syntax for creating threads.

Modern software is inherently concurrent. Users expect responsive applications. Systems must handle many simultaneous clients. Hardware provides many cores that demand parallel utilization. These realities make concurrent and parallel programming essential skills for every serious software engineer.

The goal is not to avoid concurrency and parallelism but to use them wisely. Structure programs for clarity. Execute in parallel for performance. Handle the inherent complexity with appropriate tools and techniques. Build systems that are correct, responsive, and efficient.

That is the paradigm. That is the challenge. That is the craft.

Tags

Related Articles

Design Patterns: The Shared Vocabulary of Software

A comprehensive guide to design patterns explained in human language: what they are, when to use them, how to implement them, and why they matter for your team and your business.

Clean Architecture: Building Software that Endures

A comprehensive guide to Clean Architecture explained in human language: what each layer is, how they integrate, when to use them, and why it matters for your business.

gRPC: The Complete Guide to Modern Service Communication

A comprehensive theoretical exploration of gRPC: what it is, how it works, when to use it, when to avoid it, its history, architecture, and why it has become the backbone of modern distributed systems.