BDD for Agile Teams: The Complete Theory Guide — No Code, Just Clarity

Understand Behavior Driven Development from the ground up. What it means for QA, developers, product owners, scrum masters, and PMs. Real conversations, team scenarios, diagrams, and practical examples without a single line of code.

BDD for Agile Teams: The Complete Theory Guide

Explaining BDD to a Child

Imagine you ask your little sibling to draw a cat.

You say: “Draw me a cat.”

They draw something. You look at it. It has two legs, no tail, and what appears to be a hat.

You say: “That is not a cat.”

They say: “You said draw a cat. I drew a cat.”

You realize the problem. You had a picture of a cat in your head. They had a completely different picture. You used the same word but meant completely different things.

Now imagine a different approach.

You say: “Draw me an animal with four legs, pointy ears, a long tail, and whiskers near its nose. The tail should be up when it is happy.”

They draw. You look. It is a cat. It is the right cat.

The second approach is Behavior Driven Development.

BDD is the practice of describing what software should do in such specific, agreed-upon detail that everyone — the developer, the tester, the product owner, and the customer — has the same picture in their head before anyone writes a single line of code.

That is all it is.

Everything else is process built around that one idea.

The Problem BDD Solves

Before BDD existed, teams worked like this.

The product manager writes a requirement: “Users should be able to reset their password.”

The developer reads it and builds a password reset form. It sends a reset link to the email on file. Done.

QA tests it. They try to reset a password for an account that does not exist. The system crashes. That scenario was never considered.

They try to click the reset link twice. The second click says “invalid token.” But should it? Or should it gently say “this link has already been used”? Nobody decided.

They try to reset a password for an account locked for suspicious activity. Should that be allowed? Nobody specified.

The ticket goes back to the developer. The developer asks the product manager. The product manager asks the customer. Three days later, everyone has an answer. The developer changes the code. QA tests again.

This cycle is called “the discovery of missing requirements during testing.” It is expensive. It is frustrating. And it happens in virtually every software team that does not practice BDD.

BDD is the antidote.

BDD moves the discovery of missing requirements to before development begins.

What BDD Is Not

BDD is not a testing tool.

This is the most common misunderstanding. Teams hear “behavior driven” and think it is about automated tests. They install a testing library, write some test scripts, and declare that they are “doing BDD.”

They are not.

BDD is a collaboration practice. It is a conversation methodology. The automated tests are a byproduct of that conversation, not the main event.

BDD is also not just for QA. The mistake teams make is treating BDD as QA’s responsibility. “Give your scenarios to QA. QA will write the tests.” This defeats the purpose entirely.

BDD is a three-way conversation between the person who knows the business (product owner), the person who tests the software (QA), and the person who builds it (developer). All three sit together. All three contribute. None of them can do it alone.

BDD is also not only for large projects. Even a one-person team writing a small web application benefits from the practice of writing down, in plain language, what the software is supposed to do, before writing code.

The Vocabulary of BDD

BDD introduced a specific vocabulary for writing requirements. This vocabulary is simple. It has three parts.

Given. The starting state. What is true before anything happens. The context.

When. The action. What the user does. The trigger.

Then. The outcome. What should happen as a result.

This structure is called a scenario. A collection of scenarios for one feature is called a feature file.

Here is an example in plain English, before we talk about any tool or format.

Feature: Password Reset

Picture a customer who has forgotten their password. They visit the login page and click “Forgot my password.” What should happen?

Before BDD, the answer lived in someone’s head and was never fully written down.

With BDD, the team writes it out, scenario by scenario.

Scenario 1: The basic happy path.

- Given I am a registered user with the email address “alice@example.com”

- When I request a password reset for “alice@example.com”

- Then I should receive a reset email at “alice@example.com”

- And the email should contain a link that expires in 24 hours

Scenario 2: The account does not exist.

- Given no account exists for the email “nobody@example.com”

- When I request a password reset for “nobody@example.com”

- Then I should see the message “If that email is registered, you will receive a reset link”

- And no email should be sent

Note: The message does not tell the user whether the account exists. This is a security requirement. The QA engineer knows to test this. Without writing it explicitly, it would likely be forgotten.

Scenario 3: The link is used once and then expires.

- Given I have received a valid password reset link

- When I follow the link and change my password successfully

- And I try to follow the same link again

- Then I should see the message “This reset link has already been used or has expired”

Scenario 4: The account is locked.

- Given my account has been locked due to suspicious activity

- When I request a password reset

- Then I should see the message “Your account is temporarily locked. Please contact support.”

- And no reset email should be sent

Notice what happened. The single vague requirement “Users should be able to reset their password” became four precise scenarios covering four distinct situations.

A developer reading these four scenarios has no ambiguity. A QA engineer has four specific test cases. A product owner can verify that these four scenarios match their intent.

The cat is drawn correctly.

The Three Amigos: The Core of BDD

The term “Three Amigos” is the nickname for the BDD discovery conversation.

The Three Amigos are:

- The product owner (or business analyst) — who knows what needs to be built and why

- The developer — who knows how it could be built and what constraints exist

- The QA engineer — who thinks about what could go wrong and what edge cases exist

These three people sit together for a short meeting — usually 30 to 60 minutes — before a story is developed. The goal is to write scenarios together until everyone has the same picture in their head.

This is not a requirements document review. It is a conversation.

Here is what a real Three Amigos meeting sounds like.

A Real Three Amigos Conversation

The story: “As a customer, I want to apply a discount code at checkout.”

The product owner, Maya, opens the conversation.

Maya: “Okay. The idea is simple. During checkout, customers can type a discount code. If the code is valid, the discount applies to the total.”

Carlos (developer): “What counts as ‘valid’? Does the code expire? Can it be used more than once?”

Maya: “Good questions. Codes have an expiration date. And yes, each code can only be used a set number of times. Some are one-time use. Some are unlimited.”

Sofia (QA): “What happens when I apply a code, start a session, leave, come back, and then try to check out? Is the discount still applied?”

Maya: “Hmm. The discount should persist in the cart session.”

Carlos: “What if the product I discounted is no longer in stock by the time I come back? Does the discount still apply if I replace it with something else?”

Maya: “No. The discount applies to the cart as a whole, not to a specific item. If you change your cart, the code is still valid.”

Sofia: “What about this: I apply code SAVE10 which gives me 10% off. I also have a loyalty reward that gives me 5% off. Can they stack?”

Maya pauses. “I don’t know. Let me check with the business team… Okay, I just heard back. Discount codes and loyalty rewards cannot be stacked. If both are applied, only the larger one counts.”

Carlos: “We need to be explicit about that. What message does the user see?”

Maya: “Something like: ‘Your loyalty discount of 5% is lower than your code discount of 10%. The code discount has been applied.’”

Sofia writes a new scenario.

The meeting continues. By the end, they have written eight scenarios. Three are happy paths. Five are edge cases that nobody had considered at the start.

If that meeting had not happened, five of those edge cases would have been discovered during testing. Some might have reached production. The customer would have found them.

The Three Amigos meeting is cheap. Production bugs are expensive.

The Roles, Explained

Let us spend serious time with each role. Not what the job title says. What BDD actually asks each person to do.

The Product Owner

The product owner (PO) is the voice of the business in BDD. They bring the “why” and the “what.”

The PO knows what customers need. They know the business rules. They know the regulatory constraints. They know what success looks like from a business perspective.

In BDD, the PO has one critical job: define acceptance criteria as scenarios before development begins.

Not after. Not during. Before.

This is a shift for many product owners. The traditional workflow is: write a user story, put it in the backlog, let developers figure out the details. BDD says no. The PO must think through the scenarios for each story.

This is uncomfortable at first. It requires the PO to think deeply about edge cases that feel like “developer problems.” But they are not developer problems. They are business problems. They require business decisions.

Should an expired code give the user a clear message or a generic error? That is a business decision. Should a locked account be allowed to reset its password? That is a business decision. Should discount codes stack? That is a business decision.

The PO does not need to write perfect Gherkin syntax. They need to think through the scenarios in conversation with the team.

What the PO brings to the Three Amigos meeting:

- The user story (“As a customer, I want to…”)

- The business rules they already know

- Questions they have not yet answered

- The acceptance criteria they have drafted

What the PO takes away from the Three Amigos meeting:

- Edge cases they had not thought about

- Questions to bring back to the business

- Scenarios written in plain language that they can use to verify the feature when it is built

The QA Engineer

The QA engineer (or quality assurance engineer) is the professional skeptic. Their job in BDD is to think about what could go wrong.

Developers think about how to build something. Product owners think about what to build. QA engineers think about everything that could go wrong, be misunderstood, or fail unexpectedly.

In BDD, the QA engineer has one critical job: ask the questions nobody else is asking.

This is the QA superpower. Where the developer sees a system, QA sees a thousand users doing unexpected things. Where the PO sees the happy path, QA sees the person who types their email in all caps, or who presses the back button after submitting, or who has two active sessions simultaneously.

QA engineers bring the edge cases. They are the people in the Three Amigos meeting who say “but what if…” and make everyone uncomfortable in a productive way.

What the QA engineer brings to the Three Amigos meeting:

- Questions about edge cases

- Boundary conditions (“what if the discount is 100%? What if it is 0%? What if someone types a negative number?”)

- Questions about concurrent scenarios (“what if two users try to use the same one-time code at the same time?”)

- Questions about error states

What the QA engineer takes away from the Three Amigos meeting:

- A complete set of scenarios they can use as a test plan

- Clarity on expected behavior in edge cases

- Confidence that their test cases reflect actual business requirements

In BDD, QA shifts from reactive testing (finding bugs after development) to proactive specification (preventing bugs by clarifying requirements before development).

This is the single most important shift BDD creates for QA engineers. Instead of asking “does this work?” after the fact, they ask “what should this do?” before the fact.

The Developer

The developer in BDD is not just a person who writes code to match a specification. They are an active participant in creating the specification.

Developers think about implementation constraints. They know what is easy, what is hard, and what is technically impossible. They know when a business rule will require significant system changes versus a simple configuration change.

This knowledge is invaluable in the Three Amigos meeting. When the PO says “discount codes cannot stack,” the developer might say “if the code was applied first and then the loyalty reward was loaded, our system does not know about the code when the loyalty module runs. We would need to change the checkout pipeline.” The PO might then adjust the requirement or accept the technical constraint.

These decisions happen in the meeting, not after the developer has spent two days building the wrong thing.

What the developer brings to the Three Amigos meeting:

- Technical constraints (“our payment system does not support split discounts”)

- Questions about implementation assumptions (“when you say ‘apply the larger discount,’ do you mean larger in percentage or larger in absolute dollar value?”)

- Edge cases from the system’s perspective (“what if the discount calculation produces a negative total?”)

What the developer takes away from the Three Amigos meeting:

- Clear, unambiguous scenarios they can work from

- Confidence that they understand what they are building

- A Definition of Done that is explicit and testable

The Scrum Master

The Scrum Master is not a Three Amigos participant in the same way. They do not contribute domain knowledge or technical constraints. But they have an important role in BDD: they are the facilitator and protector of the process.

The Scrum Master ensures the Three Amigos meetings happen. They schedule them. They timebox them. They notice when a team starts skipping them because of “time pressure” and they push back on that pressure.

The Scrum Master also pays attention to patterns. If the same type of edge case keeps being discovered late in every sprint — if, say, every sprint produces at least two “discovered during testing” bugs related to user state — the Scrum Master brings this to the retrospective.

“We keep finding state-related bugs late. What can we do differently?”

The answer is usually: better scenarios in the Three Amigos meeting. The Scrum Master helps the team learn from its own patterns.

The Scrum Master also protects the Three Amigos meeting from being treated as optional. In many teams, when sprint planning runs long, the first thing cut is the Three Amigos meeting. The Scrum Master recognizes this as a false economy.

Spending thirty minutes on a Three Amigos meeting saves, on average, one to two days of rework. That is a ten to twenty times return on investment. The Scrum Master understands this and defends the practice.

The Scrum Master’s BDD responsibilities:

- Schedule and protect the Three Amigos meetings

- Facilitate when conversations get stuck

- Track metrics: how many bugs are discovered before versus after development?

- Raise patterns in retrospectives

- Educate the team on the value of the practice when enthusiasm wanes

- Ensure new team members understand the process

The Project Manager

In a Scrum context, the Project Manager (PM) often overlaps with or is replaced by the Product Owner. But in many organizations, the PM is a separate role focused on timelines, budgets, and stakeholder communication.

For a PM, BDD is primarily a risk management tool.

Bugs discovered in production are expensive. A production bug in a payment system costs, on average, fifty times more to fix than the same bug discovered during development. The Three Amigos meeting is essentially a cheap insurance policy against expensive production bugs.

The PM’s interest in BDD is that it makes delivery more predictable. When scenarios are clear before development begins, estimates are more accurate. When acceptance criteria are explicit, the “done” state is unambiguous. When QA has a complete set of scenarios written before testing begins, testing time is predictable.

The PM does not need to attend Three Amigos meetings. But they need to understand BDD well enough to advocate for it when the schedule is tight.

“We are behind. Skip the Three Amigos meeting for this story.”

The PM who understands BDD pushes back on this idea. They know that skipping the meeting does not save time. It shifts time — from the front of the sprint (where it is cheap) to the back of the sprint or post-release (where it is expensive).

The PM’s BDD responsibilities:

- Understand the ROI of BDD to advocate for it under pressure

- Track metrics: sprint completion rate, post-sprint bug rate, rework time

- Communicate BDD value to business stakeholders

- Ensure BDD ceremonies are included in sprint capacity planning

How BDD Fits into the Scrum Ceremonies

BDD does not replace Scrum ceremonies. It plugs into them. Here is where each BDD activity lives in the Scrum cycle.

Sprint Cycle Timeline

─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

BEFORE THE SPRINT

│

│ Backlog Refinement

│ └─ PO presents upcoming stories

│ └─ Team asks clarifying questions

│ └─ Stories get sized if scenarios are clear enough

│ └─ Stories are marked "ready" only when Three Amigos

│ is scheduled or complete

│

SPRINT PLANNING

│ └─ Team pulls "ready" stories into the sprint

│ └─ Three Amigos meetings are scheduled for Day 1 or 2

│

SPRINT (Days 1-2)

│ └─ Three Amigos meetings happen for each story

│ └─ Scenarios are written in plain language

│ └─ PO signs off on scenarios as acceptance criteria

│

SPRINT (Days 2-10)

│ └─ Developers build based on agreed scenarios

│ └─ QA prepares test cases from the same scenarios

│

SPRINT (Days 8-10)

│ └─ QA tests against the agreed scenarios

│ └─ If behavior matches scenario: story passes

│ └─ If behavior does not match scenario: story fails

│

SPRINT REVIEW

│ └─ PO reviews completed stories

│ └─ Scenarios serve as demonstration script

│

RETROSPECTIVE

│ └─ How many scenarios were discovered AFTER development?

│ └─ What can we improve in Three Amigos?

─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────What BDD Changes for Each Role

Let us be concrete about the before and after.

For the Product Owner

Before BDD:

The PO writes a user story and acceptance criteria in bullet points.

“User can reset password. Email link sent. Link expires. Error for invalid email.”

Five bullet points that seem clear but leave dozens of questions unanswered.

After BDD:

The PO participates in writing four to ten scenarios in plain language. Each scenario is a specific, testable case. The PO can look at the completed feature and check each scenario personally. No ambiguity. No “I thought you meant…”

The PO also realizes something unexpected: writing scenarios is hard at first. It forces them to actually think through requirements instead of gesturing at them. But after a few sprints, it becomes natural, and requirements are cleaner and less likely to generate rework.

For QA

Before BDD:

QA receives a completed feature and writes test cases based on their understanding of the requirement. They often find mismatches between what the developer built and what the requirement intended. Some mismatches are documented as bugs. Some are argued about (“this is a feature, not a bug”).

After BDD:

QA participates in writing scenarios before development begins. Their test cases come directly from the agreed scenarios. When testing, they are not discovering what the software does — they are verifying that it does what was agreed. The conversation about what is a bug versus a feature already happened in the Three Amigos meeting.

QA finds fewer bugs in testing. This sounds counterintuitive. Fewer bugs in testing means QA is doing their job. The bugs were prevented, not discovered.

For the Developer

Before BDD:

The developer reads a story, makes assumptions, builds something, and then learns during QA or demo that their assumptions were wrong. They rework. Sometimes significantly.

After BDD:

The developer participates in writing scenarios. They raise technical questions early. By the time they start building, they have explicit acceptance criteria. They know they are done when all agreed scenarios produce the expected behavior.

Rework drops sharply. The developer spends less time interpreting and more time building.

For the Scrum Master

Before BDD:

The Scrum Master watches stories get sent back from QA, sees sprint goals missed, watches the team discuss the same types of misunderstandings repeatedly. They run retrospectives where “better communication” is always an action item but nothing changes.

After BDD:

The Scrum Master has a concrete practice to point to. When a story is sent back, they can ask: “Was a Three Amigos meeting done for this story?” If no, the root cause is clear. If yes, they can examine the scenarios and find where the scenario missed a case.

The Scrum Master can measure improvement. Bugs before BDD: 8 per sprint. Bugs after BDD: 2 per sprint. Stories sent back for rework before BDD: 3 per sprint. After BDD: 0.5 per sprint.

The Scrum Master can prove that BDD is working.

The Gherkin Language

BDD scenarios have a formal syntax called Gherkin. It is not a programming language. It is a structured natural language. Anyone can read it. A non-technical stakeholder can verify it.

Gherkin uses specific keywords. Here they are, with plain-language explanations.

Feature — The name of the functionality being described.

Scenario — One specific case within that feature.

Given — The starting condition. What is true before anything happens.

When — The action the user or system takes.

Then — The expected outcome.

And — Used to continue a Given, When, or Then when you have more than one condition.

But — Used like “And” but to express a negative or contrasting condition.

Background — A set of Given steps that apply to every scenario in the feature, written once at the top.

Scenario Outline — A template scenario that runs multiple times with different data.

Examples — The table of data used with a Scenario Outline.

# — A comment. Ignored by tools. Useful for notes.

Here is a complete Gherkin feature file in plain language, with no code, just structure.

Feature: Discount Code at Checkout

As a customer

I want to apply a discount code when I check out

So that I can save money on my purchase

Background:

Given I am a logged-in customer with items in my cart

And the cart total before any discount is $100.00

Scenario: Applying a valid percentage discount code

When I apply the discount code "SAVE10"

Then my cart total should be $90.00

And I should see the message "Discount code SAVE10 applied: 10% off"

Scenario: Applying a code that does not exist

When I apply the discount code "NOTACODE"

Then my cart total should remain $100.00

And I should see the message "This discount code is not valid"

Scenario: Applying a code that has expired

Given the code "SUMMER24" expired on January 1, 2025

When I apply the discount code "SUMMER24"

Then my cart total should remain $100.00

And I should see the message "This discount code has expired"

Scenario: Applying a one-time code that has already been used

Given the code "WELCOME1" has already been used by another customer

When I apply the discount code "WELCOME1"

Then my cart total should remain $100.00

And I should see the message "This discount code has already been used"

Scenario: Code discount is larger than loyalty discount

Given I have a loyalty reward giving 5% off

When I apply the discount code "SAVE10" (10% off)

Then only the code discount should be applied

And my cart total should be $90.00

And I should see "Code discount applied (10%). Your loyalty discount of 5% was not applied."

Scenario Outline: Applying various valid discount amounts

When I apply the discount code "<code>"

Then my cart total should be "<expected_total>"

Examples:

| code | expected_total |

| SAVE5 | $95.00 |

| SAVE10 | $90.00 |

| SAVE20 | $80.00 |

| SAVE50 | $50.00 |Notice that this file has no technology. No programming language. No test runner. It is readable by everyone on the team.

The product owner reads it and verifies the business rules are correct. The QA engineer uses it as a test plan. The developer uses it as acceptance criteria. The Scrum Master uses it as the Definition of Done for the story.

The Living Documentation Idea

One of the most powerful concepts in BDD is the idea of living documentation.

Traditional documentation goes stale. A developer writes a technical spec in week one. By week six, the code has changed three times but the spec was not updated. Now the spec lies. It describes behavior the system no longer has.

Feature files in BDD are living documentation because they are linked to the software. When the software changes, the scenarios must be updated — otherwise the automated tests that run from those scenarios will fail.

This means the feature files are always accurate. They always describe what the system actually does. They are the single source of truth.

For a new team member, this is invaluable. Instead of asking colleagues “how does the password reset work?”, they read the feature file. Every scenario is documented. Every edge case is covered. The documentation is accurate because the tests enforce it.

For a product owner, this means the requirement library is always current. They can read the feature files for any part of the system and know exactly how it behaves.

For an auditor or compliance officer, this is evidence. The software behaves as specified. The specification is tested automatically. Every commit to the codebase runs against the specification and proves compliance.

Common Mistakes Teams Make With BDD

BDD is simple in concept but surprisingly easy to do poorly. Here are the most common mistakes and what to do instead.

Mistake 1: Treating BDD as a QA-Only Practice

The mistake: The product owner writes user stories. The developer builds them. QA writes Gherkin scenarios after development to “document” what was built.

Why it fails: This is not BDD. This is automated documentation. The scenarios describe what the developer built, not what the business needs. Edge cases that were not discovered during development are still not discovered. Nothing has improved.

The fix: BDD scenarios must be written before development begins. The Three Amigos conversation must happen first. The scenarios are the input to development, not the output.

Mistake 2: Writing Scenarios in Technical Language

The mistake: “Given the database has a record in the users table with status=‘ACTIVE’ and email=‘alice@example.com’…”

Why it fails: No product owner can verify this. It is a test written by a developer for a developer. It tests the implementation, not the behavior. If the database schema changes, the scenario breaks even if the behavior is correct.

The fix: Write scenarios in the Ubiquitous Language of the business. “Given Alice has a registered account.” The technical details of how that state is achieved are irrelevant to the scenario.

Mistake 3: One Scenario per Feature

The mistake: Writing only the happy path. “Given a user, when they reset their password, then they receive an email.” One scenario. Done.

Why it fails: The happy path is never where the bugs live. The bugs live in the edge cases: expired links, non-existent accounts, locked accounts, concurrent requests. A single happy-path scenario catches nothing important.

The fix: Always write at least one unhappy path for every happy path. For most features, expect four to eight scenarios. If you have fewer than three scenarios for a non-trivial feature, you are missing something.

Mistake 4: Skipping Three Amigos When the Story “Seems Simple”

The mistake: “This story is straightforward. We do not need a meeting. Just build it.”

Why it fails: Every team that has ever skipped a Three Amigos meeting because a story seemed simple has discovered an edge case later. Without exception. The story that seems simple from the PO’s perspective often has technical constraints the developer knows about. Or QA edge cases nobody considered.

The fix: Do the Three Amigos meeting for every story. If the story truly is simple, the meeting will take ten minutes. That is not a waste of time. It is a ten-minute investment against hours of potential rework.

Mistake 5: Making Scenarios Too Long and Complex

The mistake: A single scenario that covers multiple actions, multiple outcomes, and multiple conditions. Thirty lines of Given-When-Then that read like a novel.

Why it fails: Long scenarios are hard to understand, hard to maintain, and when they fail, it is hard to diagnose what went wrong. They often try to test multiple things at once, which violates the principle that each scenario should test one specific behavior.

The fix: One scenario, one behavior. If a scenario grows beyond ten lines, ask: “Am I testing one thing or two things?” Split it.

Mistake 6: Not Updating Scenarios When Requirements Change

The mistake: Requirements change. The developer updates the code. The scenario is forgotten.

Why it fails: The scenario now lies. It describes behavior the system no longer has. Trust in the documentation erodes. The next developer who reads the scenario is confused.

The fix: Treat scenarios as first-class artifacts, equivalent to the code. A requirements change requires a scenario change. Make this part of the Definition of Done: “Scenarios are updated to reflect the current behavior.”

BDD in the Real World: Three Case Studies

Case Study 1: The E-Commerce Team

A twelve-person team at an e-commerce company adopted BDD after a disastrous holiday season.

In the previous year, they had shipped a discount code feature two days before Black Friday. It worked in testing. In production, when ten thousand customers tried to use the same discount code simultaneously, the system crashed. The code was supposed to have a maximum use of five hundred. Under concurrent load, it allowed over three thousand uses before the count was accurate.

The bug was not a code problem. It was a requirements problem. Nobody had asked: “What happens when many users apply the same code at the same time?”

The following year, with BDD, their Three Amigos meeting for the discount code feature lasted ninety minutes. By the end, they had written sixteen scenarios. One of those scenarios was: “Given the code has reached its maximum use count, when two users try to apply it simultaneously, then only one should succeed and the other should see a message saying the code is no longer available.”

The developer recognized this scenario immediately as a concurrency problem requiring careful handling. Without the scenario, it would have been missed again.

That holiday season: no incidents.

Case Study 2: The Banking Application

A banking team had a compliance requirement: all customer-facing messages must be reviewed by the legal department before being shown to customers.

Before BDD, the legal review happened after development, when the messages were already in the code. Lawyers reviewed deployed software. When they required changes, the developer had to go back, change messages, re-test, re-deploy. Three to four rounds per feature.

After BDD, the legal department became an informal participant in the Three Amigos meetings. Not for every meeting. But for any story that involved new customer-facing messages, a legal representative reviewed the scenario’s “Then” steps — which contained the exact messages — before development began.

Legal approved the messages in the scenario. The developer built the messages from the scenario. No rework. No post-development legal review. Compliance was built in from the start.

Case Study 3: The Healthcare Startup

A healthcare startup was building a patient-facing appointment booking system. The product manager had a vision. The development team had a plan. QA had a test script.

Three months in, a patient advocate from a partner hospital reviewed the system. In thirty minutes, they identified eleven scenarios the team had never considered.

What happens when a patient tries to book an appointment with a provider they have been blocked from seeing due to a conflict of interest?

What happens when a patient’s insurance changes between booking and appointment date?

What happens when a provider cancels an appointment but the patient has already traveled to the facility?

None of these were in the system. Some were legal requirements. Some were clinical safety requirements. All were important.

The product manager was mortified. Three months of work had missed eleven critical behaviors.

The team adopted BDD immediately. They brought clinicians, patient advocates, insurance coordinators, and compliance officers into Three Amigos meetings for each feature. Not all at once. Depending on the feature, the relevant expert was invited.

The remaining features of the system had explicit scenarios before development. Not eleven missing behaviors. Zero.

Diagrams: How BDD Information Flows

Understanding how information moves through a team practicing BDD helps visualize the practice.

Information Flow in BDD

BUSINESS

│

│ "Here is what we need and why"

│

▼

PRODUCT OWNER

│

│ Writes user story with draft acceptance criteria

│

▼

THREE AMIGOS MEETING

│

├── PRODUCT OWNER: "Here is the business intent"

├── QA ENGINEER: "What if this edge case happens?"

└── DEVELOPER: "Here is a technical constraint to consider"

│

│ Together they write: Gherkin Scenarios

│

▼

SCENARIOS (Plain language. Agreed by all three.)

│

├──────────────────────────────────────┐

│ │

▼ ▼

DEVELOPER QA ENGINEER

Uses scenarios as Uses scenarios as

acceptance criteria. test plan.

Builds until all Tests against

scenarios pass. each scenario.

│ │

└──────────────┬───────────────────────┘

│

▼

SPRINT REVIEW

│

Product Owner verifies

each scenario was met.

│

▼

PRODUCTION RELEASEThe Discovery Cost Timeline

WHEN DISCOVERED RELATIVE COST TO FIX

─────────────────────────────────────────────────

During Three Amigos 1x (a conversation)

During Development 5x (developer reworks)

During QA Testing 10x (cycle back to dev)

During Sprint Review 20x (missed sprint goal)

In Production 50x (emergency fix,

customer impact,

possible data issue)

─────────────────────────────────────────────────This diagram is the most powerful argument for BDD. The Three Amigos meeting costs one unit of effort. A production bug from a missed requirement costs fifty.

The BDD Maturity Ladder

Level 4: BDD as Culture

Scenarios written for every story.

Whole team understands and believes in the practice.

Business stakeholders participate in review.

Metrics show continuous improvement.

Level 3: BDD as Practice

Three Amigos meetings happen for every story.

Scenarios are agreed before development.

QA tests against scenarios.

Scenarios are updated when requirements change.

Level 2: BDD as Process

Three Amigos meetings happen for most stories.

Some scenarios are written before development.

QA sometimes catches scenarios late.

Occasional rework from missed edge cases.

Level 1: BDD as Theater

Teams say they do BDD but QA writes scenarios after development.

No Three Amigos meetings.

Gherkin is used as test documentation, not specification.

Same bugs as before. More ceremony.

Level 0: No BDD

Requirements are vague.

Edge cases discovered during testing or in production.

Rework is frequent.

Trust between PO and dev team is strained.

─────────────────────────────────────────────────────Most teams that adopt BDD start at Level 1 or Level 2. The goal is Level 3 and then, over time, Level 4.

Moving from Level 0 to Level 3 is a six to twelve month journey for most teams. It requires discipline, repetition, and leadership support. But every team that reaches Level 3 reports the same thing: they would never go back.

What a Good Scenario Looks Like vs. a Bad One

This is the most practical skill in BDD: writing scenarios that are actually useful.

Here are three comparisons.

Bad scenario:

Scenario: Login

Given a user

When they login

Then they are logged inProblems: Who is the user? What does “login” mean? What does “logged in” mean? This scenario has zero specificity. It cannot be tested. It cannot be verified. It is noise.

Good scenario:

Scenario: Successful login with correct credentials

Given I am a registered customer with email "alice@example.com" and password "Secret123"

When I enter my email and password on the login page and click "Sign In"

Then I should be redirected to my account dashboard

And I should see "Welcome back, Alice" in the navigation barThis scenario is specific, testable, and verifiable. Everyone on the team knows exactly what it means.

Bad scenario:

Scenario: Invalid login

Given a user

When they login with wrong password

Then it failsProblems: “It fails” means nothing. What does the user see? How many times can they try? What happens after too many attempts?

Good scenario:

Scenario: Login attempt with incorrect password

Given I am a registered customer with email "alice@example.com"

When I enter my email and the incorrect password "WrongPass1"

Then I should remain on the login page

And I should see the message "Incorrect email or password"

And my account should not be locked

Scenario: Account locked after too many failed attempts

Given I am a registered customer with email "alice@example.com"

And I have already attempted to login with an incorrect password 4 times today

When I attempt to login with an incorrect password a 5th time

Then I should see the message "Your account has been temporarily locked for security reasons"

And I should receive an email with instructions to unlock my accountTwo scenarios. Two specific, testable, verifiable behaviors. The product owner can verify both. QA can test both. The developer knows exactly what to build.

Bad scenario with technical language:

Scenario: DB record check

Given the user table has a row with id=1 and status='ACTIVE'

When a POST request is sent to /api/auth/login with body {"email": "alice@example.com", "password": "hash_abc123"}

Then the response should have status 200 and body {"token": "..."}Problems: The PO cannot read this. The business cannot verify it. It tests implementation, not behavior. It will break if the API path changes, even if the behavior is correct.

Good scenario (same thing, readable):

Scenario: Active customer successfully logs in

Given Alice has an active account with email "alice@example.com"

When Alice signs in with her correct password

Then Alice should be logged in to her account

And Alice should see her personal dashboardSame behavior. Written for humans, not machines.

Starting BDD: A Practical Team Roadmap

If your team has never done BDD, the following is a realistic path.

Week 1 — Awareness

One person on the team (ideally the Scrum Master or a senior developer or QA engineer) spends a week reading about BDD. Not implementing. Just learning. They bring a brief, practical summary to the team. No more than thirty minutes. Key message: “Here is the problem we have. Here is how BDD addresses it. I want to try one thing.”

Week 2 — The First Pilot Story

The team picks one story in the next sprint and agrees to do a Three Amigos meeting before building it. Just one story. The meeting is thirty minutes. Everyone brings their best questions. The team writes scenarios together in plain English. No tools. Just a shared document or a whiteboard.

The developer builds from the scenarios. QA tests against the scenarios. At sprint review, the team discusses: did the scenarios help? Were there edge cases we still missed?

Weeks 3-6 — Expanding the Practice

The team does Three Amigos meetings for more stories each sprint. Not necessarily all stories. Start with the complex ones. The stories that historically generate rework. The stories where requirements are ambiguous.

The team refines their scenario-writing skills. They learn to distinguish happy paths from edge cases. They learn to write in plain language instead of technical language.

Weeks 7-12 — Full Adoption

All stories have Three Amigos meetings. Scenarios are part of the Definition of Done. The team tracks a new metric: “bugs discovered before development begins vs. after.” The Scrum Master reports on this metric at retrospectives.

Month 4 and Beyond — Culture

BDD is no longer something the team “does.” It is something the team is. New members are onboarded with “this is how we work.” Scenarios are maintained alongside the codebase. The product owner can read the feature files for any part of the system and know exactly how it behaves.

The team discovers something unexpected. Requirements conversations are faster. Stakeholders trust the team more. Releases are smoother. The QA cycle is shorter. The team has more energy at the end of the sprint because less rework is happening.

This is the quiet success of BDD. It does not announce itself. It just gradually makes everything better.

The One Question That Summarizes BDD

If you have to explain BDD to someone in one sentence, say this:

“BDD is the practice of agreeing on exactly what the software should do before anyone builds it — in plain language that everyone can read, verify, and trust.”

That sentence contains everything.

Agreed on — it is collaborative, not one person’s opinion.

Exactly what it should do — it is specific, not vague.

Before anyone builds it — it is proactive, not reactive.

Plain language everyone can read — it is inclusive, not technical.

Verify and trust — it is the basis for quality and confidence.

Everything else in this guide is explanation of that one sentence.

Conclusion: The Team That Speaks the Same Language

Somewhere in the world right now, a developer is building a feature that a product owner will reject next Friday because it does not match what they intended.

Somewhere in the world, a QA engineer is finding bugs in a feature that went to testing without agreed acceptance criteria. They will file twelve tickets. The developer will dispute eight of them. The sprint will not finish on time.

Somewhere in the world, a customer is experiencing a bug that nobody expected because nobody asked “what happens if…?”

These things happen constantly. They are not the result of incompetence. They are the result of the natural ambiguity in human communication and the complexity of software.

BDD does not eliminate that ambiguity. But it moves the conversation that resolves it to the earliest possible moment — before development begins, when changes are cheap.

The team that practices BDD is the team that speaks the same language. The product owner, the developer, and the QA engineer look at the same scenarios and see the same thing. No translation required. No assumptions. No surprises.

They are drawing the same cat.

That is what BDD is for.

Tags

Related Articles

Architecture in Agile & Scrum: Communication, Planning & Execution

Master how to work effectively as an architect within Agile and Scrum teams. Learn to balance architectural vision with sprint velocity, communicate with product owners, and drive technical excellence in iterative development.

GitFlow + GitOps: The Complete Senior Git Guide for Agile Teams and Scrum

A comprehensive tutorial on GitFlow and GitOps best practices from a senior developer's perspective. Master branch strategy, conflict resolution, commit discipline, merge strategies, documentation, and how to be a Git professional in Agile/Scrum teams.

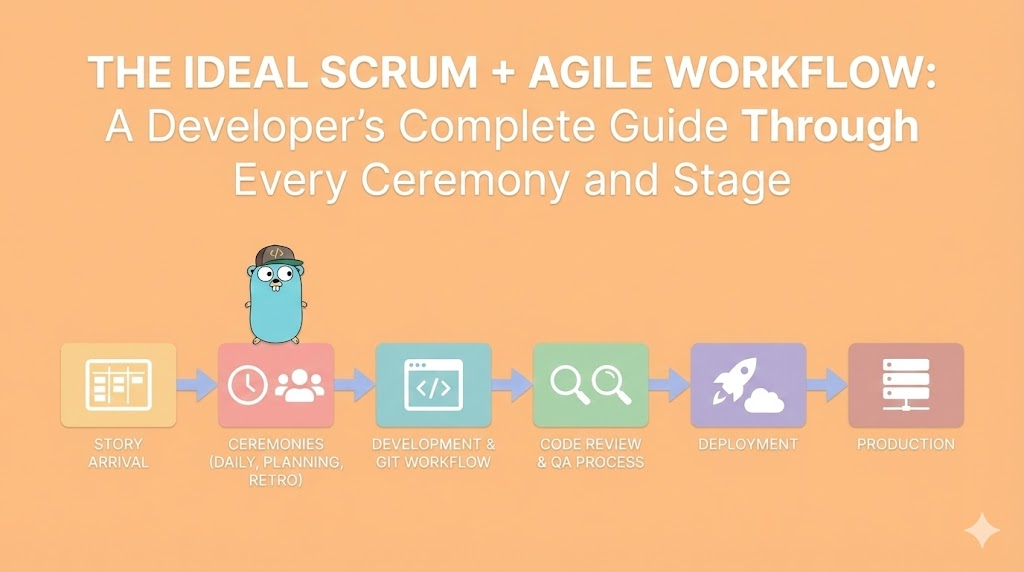

The Ideal Scrum + Agile Workflow: A Developer's Complete Guide Through Every Ceremony and Stage

A comprehensive guide to the ideal Scrum and Agile workflow from a developer's perspective. From story arrival through production deployment, understanding every ceremony, role, decision point, and what should actually happen at each stage.