Pointers vs Values en Go: Decisiones de Diseño Que Importan (Y La Mayoría Las Hace Mal)

Una exploración exhaustiva sobre cuándo usar pointers vs valores en Go, por qué es una decisión arquitectónica crítica, qué problemas causa elegir mal, cómo afecta performance, concurrencia y semántica. Con 40+ ejemplos mostrando errores comunes y patrones correctos.

Go es uno de los pocos lenguajes modernos que te da control explícito sobre si estás usando pointers o valores. No es accidental. Es una característica deliberada que permite escribir código eficiente.

Pero también es una decisión que la mayoría de los equipos toma incorrectamente.

Veo código Go constantemente donde alguien escribió:

type User struct {

ID string

Email string

Name string

}

func (u *User) Validate() bool { // ← Pointer receiver

return u.Email != ""

}

user := User{ID: "123", Email: "john@example.com"}

user.Validate() // ← Calling with value, but method expects pointerGo permite que esto funcione. El compilador inserta automáticamente un & delante de user. Y el desarrollador que escribió esto nunca se preguntó por qué decidió usar un pointer receiver.

Así que continuó con esa decisión para cada tipo, cada método, generalizando un patrón que no entiende. Ahora tiene:

- Métodos que modifican valores (por accidente)

- Concurrencia complicada (porque todo es pointer)

- Semántica confusa (¿es esto un tipo de valor o de referencia?)

- Performance subóptima (copia de pointers innecesaria)

- Aliasing bugs que son difíciles de encontrar

Y el código “funciona”. Compila. Los tests pasan. Nadie nota el problema hasta que es demasiado tarde.

Este artículo es una exploración exhaustiva y práctica sobre pointers vs valores en Go: cuándo usar cada uno, por qué importa, qué problemas causa la decisión equivocada, y cómo estructurar tu código para que la decisión sea clara y correcta.

Parte 1: El Problema Fundamental

1.1 La Distinción Que No Es Obvia

Go es un lenguaje con “pass-by-value” para casi todo. Cuando pasas algo a una función, pasas una copia. Punto.

func increment(x int) {

x++ // Incrementa la copia

}

func main() {

n := 5

increment(n)

fmt.Println(n) // 5, no 6

}Pero si quieres que una función modifique lo que pasaste, necesitas un pointer:

func increment(x *int) {

*x++ // Incrementa lo que apunta el pointer

}

func main() {

n := 5

increment(&n)

fmt.Println(n) // 6

}Esto es simple para tipos primitivos. La confusión viene cuando trabajas con structs.

1.2 La Ilusión: “El Ptr Receiver Como Defecto”

Muchos desarrolladores, especialmente los que vienen de lenguajes orientados a objetos, asumen que siempre deberían usar pointers:

// "Mejor usar pointer por seguridad"

type User struct {

Email string

}

func (u *User) SetEmail(email string) {

u.Email = email

}¿Por qué? Porque “así la función puede modificar el usuario”. Tiene lógica. Pero es la lógica equivocada.

En Go, la decisión entre pointer y value receiver no es sobre “poder modificar”. Es sobre semántica de tu tipo.

1.3 La Semántica Real

Cuando defines un método con value receiver:

func (u User) Validate() bool {

return u.Email != ""

}Estás diciendo: “Este tipo es una unidad completa y autocontenida. Operaciones sobre él no necesitan afectar el original.”

Cuando defines un método con pointer receiver:

func (u *User) SetEmail(email string) {

u.Email = email

}Estás diciendo: “Este tipo es una entidad mutativa. Operaciones sobre él pueden (y probablemente deben) afectar el original.”

Estos son enunciados arquitectónicos. No son solo “opciones técnicas”. Definen cómo tu tipo se comporta, cómo otros código lo usará, y cómo el compilador lo optimizará.

Parte 2: Por Qué Las Decisiones Importan

2.1 Problema #1: Aliasing y Mutación Inesperada

// ❌ INCORRECTO: Ptr receiver para "poder modificar"

type Config struct {

Debug bool

Port int

}

func (c *Config) SetPort(port int) {

c.Port = port

}

func setupServer(config *Config) {

config.SetPort(8080)

// ¿Qué pasó? Se modificó la original

}

func main() {

config := &Config{Debug: true, Port: 3000}

setupServer(config)

fmt.Println(config.Port) // 8080, no 3000

// ¿Quién cambió el puerto? ¿Fue setupServer?

// No está claro. Mutación implícita.

}El problema aquí es aliasing: múltiples referencias apuntando al mismo objeto, y no está claro quién puede modificarlo.

// ✅ MEJOR: Value semantics

type Config struct {

Debug bool

Port int

}

func setupServer(config Config) Config {

config.Port = 8080

return config

}

func main() {

config := Config{Debug: true, Port: 3000}

config = setupServer(config)

fmt.Println(config.Port) // 8080

// Claro: setupServer devolvió una Config modificada

}Aquí es obvio qué pasó: setupServer recibió una copia, la modificó, y devolvió la modificada.

2.2 Problema #2: Concurrencia Complicada

// ❌ INCORRECTO: Ptrs y concurrencia

type Cache struct {

data map[string]string

}

func (c *Cache) Set(key, value string) {

c.data[key] = value // ¿Thread-safe? No.

}

func (c *Cache) Get(key string) string {

return c.data[key] // ¿Thread-safe? No.

}

func main() {

cache := &Cache{data: make(map[string]string)}

go func() {

for i := 0; i < 1000; i++ {

cache.Set("key", "value")

}

}()

go func() {

for i := 0; i < 1000; i++ {

_ = cache.Get("key")

}

}()

// Race condition

}Con pointers, múltiples goroutines accediendo al mismo objeto necesitan sincronización cuidadosa.

// ✅ MEJOR: Value semantics + channels

type Cache struct {

data map[string]string

}

type CacheOp struct {

op string // "get", "set"

key string

value string

resp chan string

}

func cacheSupervisor(ops chan CacheOp) {

cache := Cache{data: make(map[string]string)}

for op := range ops {

if op.op == "set" {

cache.data[op.key] = op.value

} else if op.op == "get" {

op.resp <- cache.data[op.key]

}

}

}

func main() {

ops := make(chan CacheOp)

go cacheSupervisor(ops)

// Ahora cada goroutine envía mensajes al supervisor

// No hay acceso directo al cache. No hay race condition.

}Con value semantics, evitas el acceso concurrente directo.

2.3 Problema #3: Semántica Confusa en APIs

// ❌ INCORRECTO: Inconsistencia de semántica

type User struct {

ID string

Email string

}

func NewUser(id, email string) *User { // ← Retorna ptr

return &User{ID: id, Email: email}

}

func (u *User) Validate() bool { // ← Ptr receiver

return u.Email != ""

}

func (u User) String() string { // ← Value receiver

return fmt.Sprintf("User(%s)", u.ID)

}

// Ahora el usuario de esta API está confundido:

// "¿NewUser retorna un ptr, pero String() es value receiver?

// ¿Debo tratar User como ptr o value?"

func main() {

user := NewUser("123", "john@example.com")

if user.Validate() { // ← Ptr receiver

fmt.Println(user.String()) // ← Value receiver

}

// Funciona, pero es confuso

}El API envía señales contradictorias sobre cómo debería usarse User.

// ✅ MEJOR: Semántica consistente

type User struct {

ID string

Email string

}

func NewUser(id, email string) User { // ← Retorna valor

return User{ID: id, Email: email}

}

func (u User) Validate() bool { // ← Value receiver

return u.Email != ""

}

func (u User) String() string { // ← Value receiver

return fmt.Sprintf("User(%s)", u.ID)

}

// Para modificar:

func (u User) WithEmail(email string) User {

u.Email = email

return u

}

func main() {

user := NewUser("123", "john@example.com")

if user.Validate() {

fmt.Println(user.String())

updatedUser := user.WithEmail("jane@example.com")

fmt.Println(updatedUser.String())

}

// Claro: User es un tipo de valor inmutable

// Para modificar, creas uno nuevo

}Ahora es obvio que User es un tipo de valor.

Parte 3: Cuándo Usar Pointers

3.1 Caso #1: Tipos Mutables Grandes

// ✅ CORRECTO: Ptr para tipos que se modifican frecuentemente

type Database struct {

connections map[string]*sql.DB // 1MB+ en memoria

config *Config

logger Logger

// ... más campos

}

func (db *Database) OpenConnection(name string) error {

// Modifica db.connections

db.connections[name] = newConnection()

return nil

}

func (db *Database) Close() error {

for _, conn := range db.connections {

conn.Close()

}

return nil

}

// Razón: Database es grande (1MB+). Copiar cada vez es caro.

// Database es mutable (se abre/cierra conexiones).

// Ptrs tienen sentido.La regla práctica: Si tu struct es >128 bytes y se modifica frecuentemente, considera ptr receiver.

3.2 Caso #2: Necesidad Semántica de Mutación

// ✅ CORRECTO: Ptr cuando la mutación es esencial

type Stack struct {

items []interface{}

}

func (s *Stack) Push(item interface{}) {

s.items = append(s.items, item)

}

func (s *Stack) Pop() interface{} {

if len(s.items) == 0 {

return nil

}

item := s.items[len(s.items)-1]

s.items = s.items[:len(s.items)-1]

return item

}

// Stack SEM valor semantics no tiene sentido

// Push/Pop modifican el stack

// Tiene que ser ptr3.3 Caso #3: Tipo Que Puede Ser Nil

// ✅ CORRECTO: Ptr cuando nil tiene significado

type OptionalValue struct {

Value int

}

func FindValue(id int) *OptionalValue {

// Puede devolver nil

if id < 0 {

return nil

}

return &OptionalValue{Value: id * 2}

}

func main() {

result := FindValue(5)

if result == nil {

fmt.Println("Not found")

} else {

fmt.Println(result.Value)

}

}Con values, no puedes representar “no existe”:

// ❌ INCORRECTO: Value no puede ser nil

func FindValue(id int) OptionalValue {

if id < 0 {

return OptionalValue{} // Ambiguo: ¿no encontrado o valor cero?

}

return OptionalValue{Value: id * 2}

}

// ¿OptionalValue{} significa "no encontrado" o "valor 0"?

// No está claro.3.4 Caso #4: Interface{}

// ✅ CORRECTO: Ptr cuando necesitas interfaces

type Reader interface {

Read(p []byte) (n int, err error)

}

type LogReader struct {

file *os.File

}

func (lr *LogReader) Read(p []byte) (int, error) {

return lr.file.Read(p)

}

// LogReader contiene un pointer a File

// Tiene que usar ptr receiverParte 4: Cuándo Usar Values

4.1 Caso #1: Tipos Pequeños e Inmutables

// ✅ CORRECTO: Value receiver para tipos pequeños

type Point struct {

X float64

Y float64

}

func (p Point) Distance(other Point) float64 {

dx := p.X - other.X

dy := p.Y - other.Y

return math.Sqrt(dx*dx + dy*dy)

}

func (p Point) Translate(dx, dy float64) Point {

return Point{X: p.X + dx, Y: p.Y + dy}

}

func (p Point) String() string {

return fmt.Sprintf("(%f, %f)", p.X, p.Y)

}

// Point es 16 bytes (dos float64)

// Value semantics tiene sentido

// Translate devuelve un nuevo Point (no modifica el original)La regla práctica: Si tu struct es <128 bytes y es fundamentalmente inmutable, usa value receiver.

4.2 Caso #2: Tipos Que Actúan Como Valores Primitivos

// ✅ CORRECTO: Value receiver para tipos que actúan como primitivos

type Money struct {

Amount decimal.Decimal

Currency string

}

func (m Money) Add(other Money) (Money, error) {

if m.Currency != other.Currency {

return Money{}, errors.New("currencies must match")

}

return Money{

Amount: m.Amount.Add(other.Amount),

Currency: m.Currency,

}, nil

}

func (m Money) String() string {

return fmt.Sprintf("%s %s", m.Amount, m.Currency)

}

// Money actúa como un primitivo (int, string, etc)

// Debería usar value semantics

// Add no modifica el original, devuelve uno nuevo4.3 Caso #3: Tipos que Necesitan Ser Inmutables

// ✅ CORRECTO: Value para lograr inmutabilidad

type User struct {

ID string

Email string

Name string

}

// No hay métodos que modifiquen User

// Solo métodos que devuelven información o nuevas versiones

func (u User) WithEmail(email string) User {

u.Email = email

return u

}

func (u User) String() string {

return fmt.Sprintf("%s <%s>", u.Name, u.Email)

}

func (u User) IsAdmin() bool {

return u.ID == "admin"

}

// User es efectivamente inmutable

// Cambios requieren crear una nueva instancia4.4 Caso #4: Tipos en Mapas y Slices Heterogéneos

// ✅ CORRECTO: Value para collections

type Event struct {

Type string

Timestamp time.Time

Data map[string]interface{}

}

func (e Event) String() string {

return fmt.Sprintf("[%s] %s", e.Type, e.Timestamp)

}

func main() {

events := []Event{

{Type: "login", Timestamp: time.Now()},

{Type: "purchase", Timestamp: time.Now()},

}

for _, event := range events {

fmt.Println(event.String())

}

// Value semantics hace que sea fácil almacenar en collections

}Parte 5: Los Anti-Patrones Más Comunes

5.1 Anti-Patrón #1: Ptr Receiver Para Todo

// ❌ INCORRECTO: Ptr receiver cuando value es mejor

type Rectangle struct {

Width float64

Height float64

}

func (r *Rectangle) Area() float64 {

return r.Width * r.Height

}

func (r *Rectangle) Perimeter() float64 {

return 2 * (r.Width + r.Height)

}

func (r *Rectangle) String() string {

return fmt.Sprintf("Rectangle(%.2f x %.2f)", r.Width, r.Height)

}

// ¿Por qué ptr? Rectangle es pequeño (16 bytes)

// Estos métodos no modifican nada

// Value receiver es mejor// ✅ CORRECTO

type Rectangle struct {

Width float64

Height float64

}

func (r Rectangle) Area() float64 {

return r.Width * r.Height

}

func (r Rectangle) Perimeter() float64 {

return 2 * (r.Width + r.Height)

}

func (r Rectangle) String() string {

return fmt.Sprintf("Rectangle(%.2f x %.2f)", r.Width, r.Height)

}5.2 Anti-Patrón #2: Value Receiver Cuando Necesitas Mutación

// ❌ INCORRECTO: Value receiver pero luego sorpresas

type Account struct {

Balance decimal.Decimal

}

func (a Account) Deposit(amount decimal.Decimal) {

a.Balance = a.Balance.Add(amount) // ← No modifica el original!

}

func main() {

account := Account{Balance: decimal.NewFromInt(100)}

account.Deposit(decimal.NewFromInt(50))

fmt.Println(account.Balance) // 100, not 150!

}Si necesitas mutar, usa ptr:

// ✅ CORRECTO

type Account struct {

Balance decimal.Decimal

}

func (a *Account) Deposit(amount decimal.Decimal) {

a.Balance = a.Balance.Add(amount)

}

func main() {

account := &Account{Balance: decimal.NewFromInt(100)}

account.Deposit(decimal.NewFromInt(50))

fmt.Println(account.Balance) // 150

}O devuelve un nuevo valor:

// ✅ TAMBIÉN CORRECTO: Value con devolución

type Account struct {

Balance decimal.Decimal

}

func (a Account) Deposit(amount decimal.Decimal) Account {

a.Balance = a.Balance.Add(amount)

return a

}

func main() {

account := Account{Balance: decimal.NewFromInt(100)}

account = account.Deposit(decimal.NewFromInt(50))

fmt.Println(account.Balance) // 150

}5.3 Anti-Patrón #3: Mezclar Ptr y Value Inconsistentemente

// ❌ INCORRECTO: Inconsistencia confusa

type User struct {

ID string

Email string

}

func NewUser(email string) *User { // ← Retorna ptr

return &User{Email: email}

}

func (u User) Email() string { // ← Value receiver

return u.Email

}

func (u *User) SetEmail(email string) { // ← Ptr receiver

u.Email = email

}

// ¿Debo tratar User como ptr o value?

// API es confusa// ✅ CORRECTO: Consistencia

// Opción A: Todo values

type User struct {

ID string

Email string

}

func NewUser(email string) User { // ← Retorna valor

return User{Email: email}

}

func (u User) Email() string { // ← Value receiver

return u.Email

}

func (u User) WithEmail(email string) User { // ← Devuelve nuevo valor

u.Email = email

return u

}

// Opción B: Todo ptrs

type User struct {

ID string

Email string

}

func NewUser(email string) *User { // ← Retorna ptr

return &User{Email: email}

}

func (u *User) Email() string { // ← Ptr receiver

return u.Email

}

func (u *User) SetEmail(email string) { // ← Modifica original

u.Email = email

}5.4 Anti-Patrón #4: Ptr Receiver en Interfaz Interface{}

// ❌ INCORRECTO: Ptr receiver, luego sorpresas con interface{}

type Logger interface {

Log(msg string)

}

type ConsoleLogger struct{}

func (cl *ConsoleLogger) Log(msg string) { // ← Ptr receiver

fmt.Println(msg)

}

func main() {

var logger Logger = ConsoleLogger{} // ❌ No compila!

// ConsoleLogger no implementa Logger

// (*ConsoleLogger) implementa Logger

}

// Para que compile:

var logger Logger = &ConsoleLogger{} // ✅ FuncionaSi quieres que cualquiera pueda ser logger:

// ✅ MEJOR

type Logger interface {

Log(msg string)

}

type ConsoleLogger struct{}

func (cl ConsoleLogger) Log(msg string) { // ← Value receiver

fmt.Println(msg)

}

func main() {

var logger Logger = ConsoleLogger{} // ✅ Compila

logger.Log("Hello")

}Parte 6: Decision Tree Práctico

6.1 ¿Cuándo Usar Ptr Receiver?

┌─ ¿Necesita tu método modificar el receiver?

│

├─ SÍ ──────→ Usa ptr receiver

│

└─ NO ──────┐

┌──────────────────────────────────────┐

│ │

┌─────▼─────┐ ┌────────▼────────┐

│ ¿Es el │ │ ¿Implementa la │

│ struct │ │ interfaz con │

│ >128 bytes?│ │ ptr receiver? │

└─────┬─────┘ └────────┬────────┘

│ │

SÍ │ NO SÍ │ NO

│ │ │ │

▼ ▼ ▼ ▼

Ptr Value Ptr Value6.2 La Regla Simple (90% de Casos)

type MyType struct {

// Campos

}

// Pregúntate:

// 1. "¿Es MyType <128 bytes?" → Value receiver

// 2. "¿MyType se modifica después de creación?" → Ptr receiver

// 3. "¿Necesito nil semantics?" → Ptr receiver

// 4. "¿Lo usaré en maps/slices?" → Value receiver

// 5. "¿Actúa como un primitivo?" → Value receiver

// 6. "¿Lo usaré concurrentemente?" → Ptr receiver (o mejor: channels)

// Si no está claro: Value receiver (es más conservador)Parte 7: El Impacto en Arquitectura

7.1 Value Semantics → Functional-ish

// ✅ Value semantics anima funcional style

type Order struct {

ID string

Items []Item

Total Money

}

func (o Order) AddItem(item Item) Order {

o.Items = append(o.Items, item)

o.Total = o.Total.Add(item.Price)

return o

}

func (o Order) ApplyDiscount(percent float64) Order {

o.Total = o.Total.Multiply(decimal.NewFromFloat(1 - percent/100))

return o

}

func CreateOrder(id string) Order {

return Order{ID: id, Items: []Item{}, Total: Money{}}

}

func main() {

order := CreateOrder("123")

order = order.AddItem(Item{Name: "Widget", Price: Money{Amount: decimal.NewFromInt(10)}})

order = order.ApplyDiscount(10) // 10% descuento

// Functional: cada operación devuelve un nuevo Order

// No hay mutación invisible

}7.2 Ptr Semantics → OOP-ish

// ✅ Ptr semantics permite OOP style

type OrderService struct {

repo Repository

log Logger

}

func (os *OrderService) CreateOrder(userID string) (*Order, error) {

order := &Order{ID: uuid.New().String(), UserID: userID}

if err := os.repo.Save(order); err != nil {

os.log.Error("Failed to save order", err)

return nil, err

}

return order, nil

}

func (os *OrderService) UpdateOrder(order *Order) error {

if err := os.repo.Update(order); err != nil {

os.log.Error("Failed to update order", err)

return err

}

return nil

}7.3 El Patrón Recomendado

// ✅ RECOMENDADO: Value types para dominio, Ptr para servicios

// Domain: Value semantics

type User struct {

ID string

Email string

}

func (u User) IsValid() bool {

return u.Email != ""

}

func (u User) WithEmail(email string) User {

u.Email = email

return u

}

// Service: Ptr semantics

type UserService struct {

repo Repository

}

func (us *UserService) Create(user User) error {

return us.repo.Save(user)

}

func (us *UserService) GetByID(id string) (User, error) {

return us.repo.GetByID(id)

}

// Domain es inmutable (values)

// Services manejan estado (ptrs)Parte 8: Casos De Estudio Real

8.1 Caso: Startup Que Cambió de Values a Ptrs

El Plan: “Empezamos con value receivers en todo”

type Product struct {

ID string

Price Money

}

func (p Product) Discount(percent float64) Product {

p.Price = p.Price.Multiply(decimal.NewFromFloat(1 - percent/100))

return p

}El Problema (Mes 3):

"Necesitamos actualizar precios en tiempo real.

Múltiples goroutines modifican Products.

¿Cómo sincronizamos?"

// Intentaron con values:

// - Demasiado copia

// - Difícil compartir estado

// - Imposible sincronizarLa Refactor (Semana 1):

type Product struct {

ID string

Price Money

mu sync.RWMutex

}

func (p *Product) SetDiscount(percent float64) {

p.mu.Lock()

defer p.mu.Unlock()

p.Price = p.Price.Multiply(decimal.NewFromFloat(1 - percent/100))

}Lección: “Value semantics para lectura/cálculo. Ptr + mutex para mutación compartida. No mixing.”

8.2 Caso: Empresa Que Pasó Todo a Ptrs

El Plan: “Ptrs everywhere para máxima flexibilidad”

type Point struct {

X float64

Y float64

}

func (p *Point) Distance(other *Point) float64 {

dx := p.X - other.X

dy := p.Y - other.Y

return math.Sqrt(dx*dx + dy*dy)

}El Problema (Mes 2):

"¿Por qué tengo nil pointers aquí?

¿Por qué Distance falla con 'invalid memory address'?

¿Por qué necesito nil checks en todo lugar?"

// Points no deberían ser nil

// Pero ptrs pueden serlo

// Código lleno de: if p != nil { ... }La Refactor:

type Point struct {

X float64

Y float64

}

func (p Point) Distance(other Point) float64 {

dx := p.X - other.X

dy := p.Y - other.Y

return math.Sqrt(dx*dx + dy*dy)

}

// Point es un valor

// No puede ser nil

// Código más simpleLección: “Values para tipos que no deberían ser nil. Ptrs para tipos que SÍ pueden serlo.”

Parte 9: Mejores Prácticas

9.1 Regla #1: Sé Consistente Dentro del Tipo

// ❌ INCORRECTO

type Order struct {

ID string

}

func (o Order) ID() string { return o.ID } // Value

func (o *Order) SetID(id string) { o.ID = id } // Ptr

// ✅ CORRECTO: Una u otra

// Opción A: Todo values

func (o Order) ID() string { return o.ID }

func (o Order) WithID(id string) Order {

o.ID = id

return o

}

// Opción B: Todo ptrs

func (o *Order) ID() string { return o.ID }

func (o *Order) SetID(id string) { o.ID = id }9.2 Regla #2: Documenta tu Decisión

// ✅ BIEN: Documenta por qué

type Cache struct {

data map[string]interface{} // Ptr porque: grande, mutable, compartida

mu sync.RWMutex

}

// Value semantics: Document.Validate() no modifica

// Ptr semantics: *Service.Create() escribe a BD9.3 Regla #3: Value por Defecto, Ptr por Excepción

// ✅ BIEN: Asume value receiver

type DateTime time.Time

func (dt DateTime) Format() string {

return time.Time(dt).Format(time.RFC3339)

}

// Solo usa ptr si REALMENTE lo necesitas:

// - >128 bytes

// - Mutación frecuente

// - Nil semantics

// - Sinc requerida9.4 Regla #4: Interfaz Consistente

// ✅ BIEN: La interfaz y la implementación concuerdan

type Reader interface {

Read(p []byte) (int, error)

}

type FileReader struct {

file *os.File

}

func (fr *FileReader) Read(p []byte) (int, error) { // Ptr receiver

return fr.file.Read(p)

}

// Si la interfaz espera ptr receiver, la impl usa ptr

// Si espera value, la impl usa valueParte 10: La Verdad

10.1 No Es Una Decisión Técnica Menor

Elegir entre ptr y value receiver es una decisión arquitectónica. Define:

- Si tu tipo es un “valor” o una “entidad”

- Si es inmutable o mutable

- Cómo interactúa con concurrencia

- Cómo se copia y se pasa

- Si puede ser nil

10.2 La Regla de Oro

Value Receiver = Mi tipo actúa como un VALUE

(int, string, Point, User, etc)

Pequeño, inmutable, no compartido

Ptr Receiver = Mi tipo actúa como una ENTITY

(Service, Repository, Database, etc)

Grande, mutable, compartida, compartir estado10.3 Cuando Tengas Dudas

// 1. ¿Necesita tu método modificar?

// SÍ → ptr receiver

// NO → pregunta 2

// 2. ¿Será nil alguna vez?

// SÍ → ptr receiver

// NO → pregunta 3

// 3. ¿Es >128 bytes?

// SÍ → probablemente ptr

// NO → pregunta 4

// 4. ¿Lo llamarás frecuentemente en loops?

// SÍ → considera ptr (evita copia)

// NO → value receiver probablemente está bien

// Si aún no está claro: Value receiver (más seguro)Conclusión: La Decisión Que Importa

Elegir entre ptr y value receiver no es una decisión técnica superficial. Es una declaración sobre qué es tu tipo, cómo debería comportarse, y cómo otros código interactúa con él.

Los equipos que entienden esta distinción escriben código Go más claro, más eficiente, y más fácil de mantener.

Los equipos que no entienden la distinción terminan con código que funciona, pero que es confuso, ineficiente, y lleno de bugs sutiles de concurrencia y aliasing.

La diferencia no es pequeña. Es fundamental.

Así que antes de escribir func (u *User), pregúntate: ¿Por qué User es un pointer receiver?

Si la respuesta es “porque parece lo normal” o “porque otros hicieron lo mismo”, estás tomando una decisión equivocada.

Si la respuesta es “porque User es >128 bytes y se modifica frecuentemente” o “porque puede ser nil”, está bien hecha.

Y esa diferencia, multiplicada por cien tipos en tu codebase, es la diferencia entre arquitectura buena y arquitectura mediocre.

Tags

Artículos relacionados

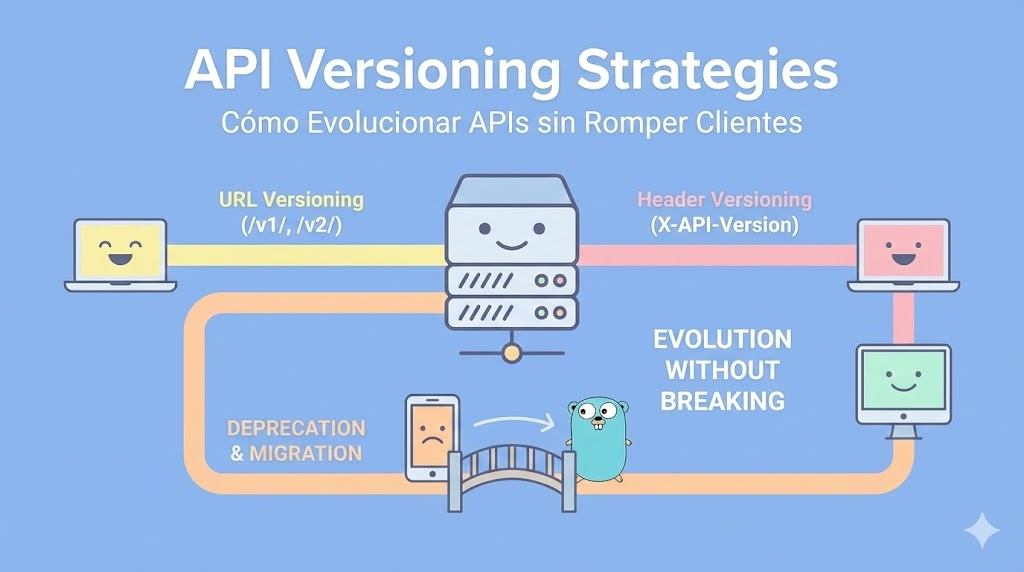

API Versioning Strategies: Cómo Evolucionar APIs sin Romper Clientes

Una guía exhaustiva sobre estrategias de versionado de APIs: URL versioning vs Header versioning, cómo deprecar endpoints sin shock, migration patterns reales, handling de cambios backwards-incompatibles, y decisiones arquitectónicas que importan. Con 50+ ejemplos de código en Go.

Arquitectura de software: Más allá del código

Una guía completa sobre arquitectura de software explicada en lenguaje humano: patrones, organización, estructura y cómo construir sistemas que escalen con tu negocio.

Automatizando tu vida con Go CLI: Guía profesional para crear herramientas de línea de comandos escalables

Una guía exhaustiva y paso a paso sobre cómo crear herramientas CLI escalables con Go 1.25.5: desde lo básico hasta proyectos empresariales complejos con flags, configuración, logging, y ejemplos prácticos para Windows y Linux.