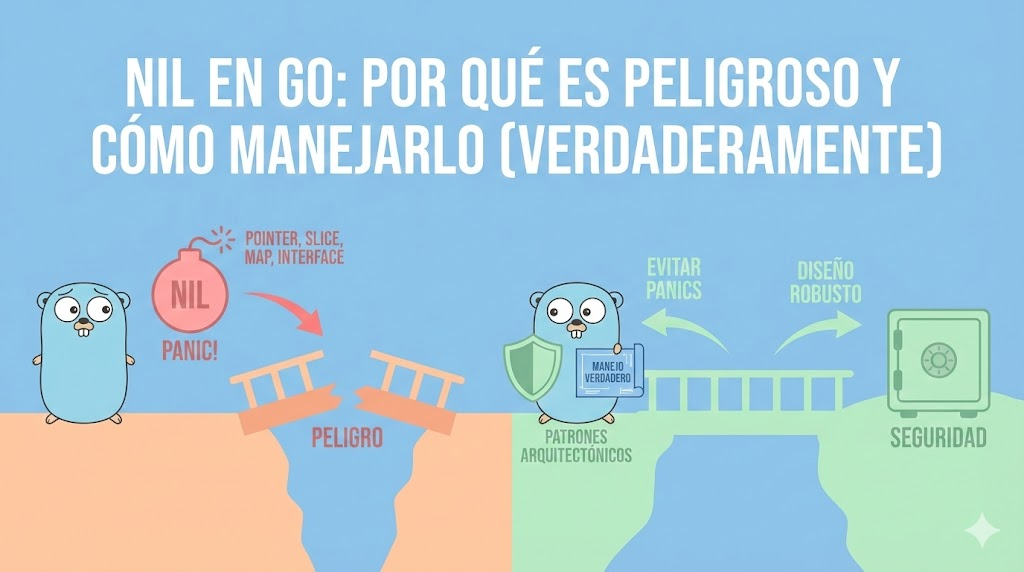

Nil en Go: Por Qué Es Peligroso y Cómo Manejarlo (Verdaderamente)

Una exploración exhaustiva sobre nil en Go: qué es, por qué causa tantos bugs, cómo afecta arquitectura, patrones para evitarlo, y cómo diseñar APIs que minimicen nil errors. Con 40+ ejemplos de código y anti-patrones reales.

Go es famoso por su manejo de errores explícito. Nadie duda de eso. Pero hay un error que Go permite silenciosamente: nil.

Un pointer nil. Un slice nil. Una interfaz con receiver nil. Un map nil. Cada uno de estos puede causar un panic en runtime que no es detectado en tiempo de compilación.

La mayoría de los lenguajes modernos han intentado resolver esto. Rust tiene Option<T>. Kotlin tiene tipos nullable explícitos. TypeScript tiene null y undefined con type checking. Todos ellos reconocen que nil/null es peligroso y que merece atención especial en el sistema de tipos.

Go no hizo nada de esto. Go dejó que nil fuera completamente implicit. Un pointer puede ser nil sin que el compilador te avise. Una función puede devolver algo que es nil sin que sea evidente del tipo. Un método puede ser llamado en un receiver nil que causará panic.

Tony Hoare, quien inventó null, lo llamó “The Billion Dollar Mistake”. Go decidió no aprender esa lección.

Pero Go lo compensó de otras formas. No con type safety (como Rust), sino con patrones arquitectónicos sensatos que minimizan el daño de nil y hacen que los nil errors sean raros y predecibles.

El problema es que la mayoría de los equipos de Go no usan esos patrones. Así que terminan con código lleno de nil checks, nil panics, y arquitectura frágil alrededor de nil.

Este artículo es una exploración exhaustiva y práctica sobre nil en Go: qué es, por qué es tan peligroso, qué patrones arquitectónicos lo minimizan, cómo diseñar APIs que eviten nil, y cómo manejar nil elegantemente cuando es inevitable.

Parte 1: Qué Es Nil, Realmente

1.1 La Definición Simple (Que Es Insuficiente)

Nil es el “valor cero” para pointers, interfaces, slices, maps, y channels. Es la ausencia de valor.

var p *int // nil

var i interface{} // nil

var s []int // nil

var m map[string]int // nil

var c chan int // nilEso es técnicamente correcto. Pero es incompleto.

1.2 Lo Que Realmente Significa

Nil significa diferentes cosas dependiendo del tipo:

Para pointers:

var p *User // nil = "no hay User"

var p2 *User = &User{} // no-nil = "hay un User"Para slices:

var s []int // nil = "no hay elementos, capacidad 0, ninguno asignado"

var s2 []int = make([]int, 0) // no-nil pero vacío = "hay un slice, pero cero elementos"

// Son diferentes:

len(s) == 0 // true

cap(s) == 0 // true

s == nil // true

len(s2) == 0 // true

cap(s2) == 0 // true

s2 == nil // falsePara maps:

var m map[string]int // nil = "no hay map"

var m2 map[string]int = make(map[string]int) // no-nil = "hay un map vacío"

// Son diferentes:

len(m) == 0 // true (pero panic si lees)

m == nil // true

len(m2) == 0 // true

m2 == nil // false

// Leer de nil map = panic

value := m["key"] // ❌ panic: assignment to entry in nil map

value := m2["key"] // ✅ OK, devuelve valor ceroPara interfaces:

var i interface{} // nil = "interfaz sin valor ni tipo"

var i2 interface{} = (*User)(nil) // no-nil = "interfaz con tipo *User, pero valor nil"

// Son diferentes:

i == nil // true

i2 == nil // false (!)

// i2 es una "interfaz de nil". Diferente a nil.1.3 El Problema: Nil No Es Un Error Explícito

En Go, un función puede devolver nil sin que sea evidente:

func GetUser(id string) *User {

if id == "" {

return nil // ← nil implícito

}

return &User{ID: id}

}

user := GetUser("")

fmt.Println(user.Name) // ❌ panic: nil pointer dereferenceEl compilador no se queja. Devolviste nil. El usuario lo recibió. El usuario lo dereferenció. Panic.

Compara con Rust:

fn get_user(id: &str) -> Option<User> {

if id.is_empty() {

return None; // Explícito

}

Some(User { id: id.to_string() })

}

let user = get_user("");

// Rust: Error! No puedes acceder a fields de Option sin unwrap

println!("{}", user.name); // ❌ Compilation errorRust te obliga a manejar el caso de “ausencia de valor”. Go te deja que lo ignores.

Parte 2: Por Qué Nil Es Tan Peligroso

2.1 Problema #1: Nil Panics son Impredecibles

// ❌ INCORRECTO: Nil puede venir de cualquier lado

func ProcessOrder(order *Order) {

// order puede ser nil

// ¿Dónde vinieron? ¿De dónde?

// No hay forma de saberlo en tiempo de compilación

total := order.CalculateTotal() // ❌ panic si order es nil

}

func main() {

order := getOrderFromDB() // Puede devolver nil

ProcessOrder(order) // Panic no predicho

}El problema:

- No hay forma de saber si una función puede devolver nil

- No hay forma de saber si una función acepta nil

- El panic puede venir de cualquier lugar

- Es un error runtime, no compiletime

// ✅ MEJOR: Explícito sobre nil

func ProcessOrder(order *Order) error {

if order == nil {

return ErrNilOrder

}

total := order.CalculateTotal()

return nil

}

// O mejor aún: No acepta nil

type Order struct { ... }

func ProcessOrder(order Order) error {

// order NUNCA puede ser nil

// No es un pointer

total := order.CalculateTotal()

return nil

}2.2 Problema #2: Nil Checks Verbosos

// ❌ INCORRECTO: Demasiados nil checks

func GetUserProfile(userID string) (*Profile, error) {

user, err := getUser(userID)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

if user == nil { // ← Nil check

return nil, ErrUserNotFound

}

preferences, err := getPreferences(user.ID)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

if preferences == nil { // ← Nil check

return nil, ErrPreferencesNotFound

}

settings, err := getSettings(user.ID)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

if settings == nil { // ← Nil check

return nil, ErrSettingsNotFound

}

return &Profile{

User: user,

Preferences: preferences,

Settings: settings,

}, nil

}El 50% del código es nil checks. Es verboso y repetitivo.

// ✅ MEJOR: No devolver nil cuando se puede evitar

func GetUser(userID string) (User, error) {

// Devuelve User (no *User), nunca nil

// O devuelve error

...

}

func GetUserProfile(userID string) (Profile, error) {

user, err := GetUser(userID)

if err != nil {

return Profile{}, err

}

preferences, err := getPreferences(user.ID)

if err != nil {

return Profile{}, err

}

settings, err := getSettings(user.ID)

if err != nil {

return Profile{}, err

}

return Profile{

User: user,

Preferences: preferences,

Settings: settings,

}, nil

}Mismo código, pero sin nil checks. Más limpio.

2.3 Problema #3: Semántica Confusa

// ❌ INCORRECTO: ¿Qué significa nil?

func FindOrder(id string) *Order {

order := &Order{}

rows := db.Query("SELECT * FROM orders WHERE id = ?", id)

if !rows.Next() {

return nil // ← ¿Significa "no encontrado" o "error"?

}

rows.Scan(&order.ID, &order.UserID, &order.Total)

return order

}

// Cuando llamas:

order := FindOrder("123")

if order == nil {

fmt.Println("Not found or error?") // Ambiguo

}¿Nil significa “no encontrado” o “error en BD” o “error de parsing”? No está claro.

// ✅ MEJOR: Semántica clara

func FindOrder(id string) (Order, error) {

var order Order

row := db.QueryRow("SELECT * FROM orders WHERE id = ? LIMIT 1", id)

err := row.Scan(&order.ID, &order.UserID, &order.Total)

if err == sql.ErrNoRows {

return Order{}, ErrOrderNotFound

}

if err != nil {

return Order{}, err

}

return order, nil

}

// Ahora es claro:

// - Error específico = orden no encontrada

// - Otro error = problema con BD

// - No hay nil = resultado válido2.4 Problema #4: Nil Interfaces (El Problema Más Sutil)

// ❌ INCORRECTO: Nil interface

type Logger interface {

Log(msg string)

}

func SetupService(logger Logger) *Service {

if logger == nil {

logger = &NullLogger{} // ← Pero logger ya es nil aquí

}

return &Service{Logger: logger}

}

// Problema:

var logger Logger // nil

service := SetupService(logger)

// Ahora:

if service.Logger != nil {

service.Logger.Log("test") // ✅ OK

} else {

fmt.Println("Logger is nil") // ❌ Nunca se ejecuta, pero creíste que sí

}El problema es que Logger puede ser nil, pero tu código asume que no. Es una trampa semántica.

// ✅ MEJOR: Requiere logger no-nil

func SetupService(logger Logger) (*Service, error) {

if logger == nil {

return nil, ErrNilLogger // Error explícito

}

return &Service{Logger: logger}, nil

}

// O mejor aún:

func SetupService(logger Logger) *Service {

// Logger es requerido. Si es nil, error durante setup, no después.

// Llamador debe asegurar que logger no es nil.

return &Service{Logger: logger}

}

// O el mejor enfoque:

type Service struct {

logger Logger

}

func NewService(logger Logger) (*Service, error) {

if logger == nil {

return nil, ErrNilLogger

}

return &Service{logger: logger}, nil

}2.5 Problema #5: Nil Errores Que Se Propagan

// ❌ INCORRECTO: Nil error se propaga silenciosamente

func GetUserEmail(id string) string {

user, err := getUser(id)

if err != nil {

return "" // ← Devuelve valor cero, no error

}

if user == nil {

return "" // ← No reporta nil, silencioso

}

return user.Email

}

func main() {

email := GetUserEmail("123")

// ¿Fue encontrado? ¿Error? ¿Nil?

// No hay forma de saberlo. Email es "".

fmt.Println(email) // Tal vez "" significa error, tal vez no

}Devolviste un valor cero y perdiste información sobre qué salió mal.

// ✅ MEJOR: Error explícito

func GetUserEmail(id string) (string, error) {

user, err := GetUser(id) // GetUser devuelve (User, error), nunca nil

if err != nil {

return "", err

}

return user.Email, nil

}

// Ahora:

email, err := GetUserEmail("123")

if err != nil {

fmt.Println("Error:", err)

} else {

fmt.Println("Email:", email)

}Parte 3: Cómo Go (Debería) Manejar Nil

3.1 El Patrón Core: Nunca Devolver Nil Si Puedes Evitarlo

// ❌ INCORRECTO: Devuelve nil frecuentemente

type UserRepository struct {

db *sql.DB

}

func (r *UserRepository) GetByID(id string) *User {

// Puede devolver nil

}

func (r *UserRepository) GetByEmail(email string) *User {

// Puede devolver nil

}

// Cada llamada necesita nil check

user := repo.GetByID("123")

if user == nil {

fmt.Println("Not found")

return

}// ✅ MEJOR: Devuelve error explícito

type UserRepository struct {

db *sql.DB

}

func (r *UserRepository) GetByID(id string) (User, error) {

// Devuelve User (no *User) o error

// Nunca nil User

}

func (r *UserRepository) GetByEmail(email string) (User, error) {

// Devuelve User (no *User) o error

// Nunca nil User

}

// Ahora nil checks no son necesarios

user, err := repo.GetByID("123")

if err != nil {

fmt.Println("Error:", err)

return

}

// user nunca es nil aquí

fmt.Println(user.Name)3.2 Patrón: Usar Values en Lugar de Pointers

// ❌ INCORRECTO: Pointers = nil possible

type User struct {

ID string

Email string

Name string

}

func (u *User) Validate() bool {

if u == nil {

return false

}

return u.Email != ""

}

// Nil checks necesarios

user := &User{}

if user == nil {

fmt.Println("No user")

return

}

if !user.Validate() {

fmt.Println("Invalid user")

return

}// ✅ MEJOR: Values = nunca nil

type User struct {

ID string

Email string

Name string

}

func (u User) Validate() bool {

// u nunca es nil

return u.Email != ""

}

// Sin nil checks

user := User{} // Valor cero, no nil

if !user.Validate() {

fmt.Println("Invalid user")

return

}3.3 Patrón: Usar Errores Para Ausencia

// ❌ INCORRECTO: nil para "no encontrado"

func FindUser(id string) *User {

// Si no existe, devuelve nil

// Pero ¿es error silencioso o esperado?

}

// ✅ MEJOR: Error para "no encontrado"

var ErrUserNotFound = errors.New("user not found")

func FindUser(id string) (User, error) {

// Si no existe, devuelve error

// Es explícito

}

// Uso:

user, err := FindUser("123")

if err == ErrUserNotFound {

fmt.Println("User does not exist")

} else if err != nil {

fmt.Println("Error finding user:", err)

} else {

fmt.Println("User:", user.Name)

}3.4 Patrón: Validar Nil en el Boundary

// ❌ INCORRECTO: Validar nil en todas partes

func (s *Service) CreateUser(user *User) error {

if user == nil {

return ErrNilUser

}

if err := s.validate(user); err != nil {

return err

}

if err := s.save(user); err != nil {

return err

}

return nil

}

func (s *Service) validate(user *User) error {

if user == nil {

return ErrNilUser

}

// ...

}

func (s *Service) save(user *User) error {

if user == nil {

return ErrNilUser

}

// ...

}

// Nil checks en todas partes// ✅ MEJOR: Validar nil en entry point

func CreateUserHandler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

var req CreateUserRequest

if err := json.NewDecoder(r.Body).Decode(&req); err != nil {

http.Error(w, "Invalid request", http.StatusBadRequest)

return

}

user := User{

Email: req.Email,

Name: req.Name,

}

if err := service.CreateUser(user); err != nil {

http.Error(w, err.Error(), http.StatusInternalServerError)

return

}

w.WriteHeader(http.StatusCreated)

}

// Service nunca recibe nil

func (s *Service) CreateUser(user User) error {

// user nunca es nil

// No necesita validación

return s.repo.Save(user)

}Parte 4: Anti-Patrones Comunes Con Nil

4.1 Anti-Patrón #1: Confundir Nil Slice Con Slice Vacío

// ❌ INCORRECTO: Tratar nil y slice vacío igual

func ProcessItems(items []int) {

if len(items) == 0 {

fmt.Println("No items")

return

}

for _, item := range items {

fmt.Println(item)

}

}

// Problema: No diferencia entre:

// - var items []int (nil)

// - items := make([]int, 0) (vacío)

// Ambos tienen len == 0, pero son diferentes// ✅ MEJOR: Ser explícito si necesita diferencia

func ProcessItems(items []int) error {

if items == nil {

return ErrNilSlice

}

if len(items) == 0 {

fmt.Println("No items")

return nil

}

for _, item := range items {

fmt.Println(item)

}

return nil

}

// O si no importa:

func ProcessItems(items []int) {

// Funciona igual con nil o vacío

for _, item := range items {

fmt.Println(item)

}

}4.2 Anti-Patrón #2: Devolver Pointer Cuando Value Bastaría

// ❌ INCORRECTO: Pointer innecesario

type Point struct {

X float64

Y float64

}

func NewPoint(x, y float64) *Point {

// ¿Por qué pointer?

return &Point{X: x, Y: y}

}

func (p *Point) Distance(other *Point) float64 {

// nil checks implícitos

if p == nil || other == nil {

return 0

}

dx := p.X - other.X

dy := p.Y - other.Y

return math.Sqrt(dx*dx + dy*dy)

}

// Uso:

p1 := NewPoint(0, 0)

p2 := NewPoint(3, 4)

dist := p1.Distance(p2)

// ¿Qué si p1 es nil? Depende del implementador.// ✅ MEJOR: Value cuando sea posible

type Point struct {

X float64

Y float64

}

func NewPoint(x, y float64) Point {

// Value, nunca nil

return Point{X: x, Y: y}

}

func (p Point) Distance(other Point) float64 {

// p y other nunca son nil

dx := p.X - other.X

dy := p.Y - other.Y

return math.Sqrt(dx*dx + dy*dy)

}

// Uso:

p1 := NewPoint(0, 0)

p2 := NewPoint(3, 4)

dist := p1.Distance(p2)

// Siempre funciona. Sin nil surprises.4.3 Anti-Patrón #3: Interface Nil Que No Es Realmente Nil

// ❌ INCORRECTO: Interface nil confusa

type Logger interface {

Log(msg string)

}

type Service struct {

Logger Logger // Puede ser nil

}

func (s *Service) DoSomething() {

if s.Logger != nil {

s.Logger.Log("Starting")

}

// Pero Logger puede ser interface de nil:

var logger Logger = (*NullLogger)(nil)

s.Logger = logger

if s.Logger != nil {

s.Logger.Log("This will panic") // ❌ panic si NullLogger es nil

}

}// ✅ MEJOR: Requiere Logger válido

type Service struct {

logger Logger // Privado, nunca nil

}

func NewService(logger Logger) (*Service, error) {

if logger == nil {

return nil, ErrNilLogger

}

return &Service{logger: logger}, nil

}

func (s *Service) DoSomething() {

// logger nunca es nil

s.logger.Log("Starting")

}

// O si Logger es opcional:

type Service struct {

logger Logger // Puede ser nil

}

func (s *Service) DoSomething() {

// Validación central

logger := s.logger

if logger == nil {

logger = &NullLogger{}

}

logger.Log("Starting")

}4.4 Anti-Patrón #4: Nil Como “Valor Especial”

// ❌ INCORRECTO: Nil como valor semántico

type Config struct {

Timeout *time.Duration

}

func (c *Config) GetTimeout() time.Duration {

if c.Timeout == nil {

return 30 * time.Second // Default

}

return *c.Timeout

}

// Problemático:

// - ¿Por qué Timeout es pointer?

// - "nil" significa "usar default", pero no es obvio

// - Código verboso// ✅ MEJOR: Valor con default claro

type Config struct {

Timeout time.Duration // Valor, no pointer

}

func NewConfig() Config {

return Config{

Timeout: 30 * time.Second, // Default claro

}

}

// Si quieres hacer override:

config := NewConfig()

config.Timeout = 60 * time.Second

// O con builder:

config := NewConfig().WithTimeout(60 * time.Second)4.5 Anti-Patrón #5: Aceitar Nil Cuando Debería Requerir Valor

// ❌ INCORRECTO: Acepta nil pero solo a veces

type Repository interface {

GetUser(id string) *User // Puede devolver nil

}

type Service struct {

repo Repository

}

func (s *Service) CreateOrder(userID string) (*Order, error) {

user := s.repo.GetUser(userID)

if user == nil {

return nil, ErrUserNotFound

}

// ... procesamiento

return order, nil

}

func (s *Service) UpdateUser(userID string, updates map[string]interface{}) error {

user := s.repo.GetUser(userID)

if user == nil {

return ErrUserNotFound

}

// ... actualización

return nil

}

// Cada función que usa repo necesita nil checks// ✅ MEJOR: Repository siempre devuelve resultado valido o error

type Repository interface {

GetUser(id string) (User, error) // Nunca devuelve nil

}

type Service struct {

repo Repository

}

func (s *Service) CreateOrder(userID string) (*Order, error) {

user, err := s.repo.GetUser(userID)

if err != nil {

if err == ErrUserNotFound {

return nil, err

}

return nil, fmt.Errorf("failed to get user: %w", err)

}

// user nunca es nil aquí

// ... procesamiento

return order, nil

}

func (s *Service) UpdateUser(userID string, updates map[string]interface{}) error {

user, err := s.repo.GetUser(userID)

if err != nil {

return err

}

// user nunca es nil

// ... actualización

return nil

}

// Sin nil checks innecesariosParte 5: Patrones Arquitectónicos Para Evitar Nil

5.1 Patrón: Null Object

// ✅ En lugar de nil, usar Null Object

type Logger interface {

Log(msg string)

Error(msg string)

}

type NullLogger struct{}

func (nl *NullLogger) Log(msg string) {

// Do nothing, pero no panic

}

func (nl *NullLogger) Error(msg string) {

// Do nothing, pero no panic

}

type Service struct {

logger Logger // Nunca nil

}

func NewService(logger Logger) *Service {

if logger == nil {

logger = &NullLogger{} // Default null object

}

return &Service{logger: logger}

}

func (s *Service) DoSomething() {

s.logger.Log("Starting") // Nunca panic, incluso si "null"

}

// Ventajas:

// - Sin nil checks

// - Logger siempre funciona

// - NullLogger puede loguear a /dev/null o buffer5.2 Patrón: Result/Option Type

// ✅ Simular Option<T> de Rust

type Option[T any] struct {

value T

ok bool

}

func Some[T any](value T) Option[T] {

return Option[T]{value: value, ok: true}

}

func None[T any]() Option[T] {

return Option[T]{ok: false}

}

func (o Option[T]) Unwrap() (T, error) {

if !o.ok {

var zero T

return zero, ErrNone

}

return o.value, nil

}

// Uso:

func FindUser(id string) Option[User] {

if id == "" {

return None[User]()

}

return Some(User{ID: id})

}

result := FindUser("123")

user, err := result.Unwrap()

if err != nil {

fmt.Println("Not found")

} else {

fmt.Println("User:", user)

}

// Ventajas:

// - Type-safe

// - No puede olvidar el nil check (porque es un error)

// - Explícito en la firma de función5.3 Patrón: Validación en Constructor

// ✅ Validar nil en constructor, no en cada método

type Database struct {

conn *sql.DB

}

func NewDatabase(dsn string) (*Database, error) {

conn, err := sql.Open("postgres", dsn)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

// Validación aquí

if conn == nil {

return nil, ErrNilConnection

}

return &Database{conn: conn}, nil

}

// conn nunca es nil después de NewDatabase

func (db *Database) Query(query string, args ...interface{}) (Rows, error) {

// db.conn nunca es nil

return db.conn.Query(query, args...)

}

// Ventajas:

// - Nil checks centralizados

// - Métodos más simples

// - Garantía de estado válido5.4 Patrón: Type-Driven Design

// ✅ Usar tipos para evitar nil

type ValidEmail string

type ValidID string

func NewEmail(email string) (ValidEmail, error) {

if email == "" {

return ValidEmail(""), ErrEmptyEmail

}

if !strings.Contains(email, "@") {

return ValidEmail(""), ErrInvalidEmail

}

return ValidEmail(email), nil

}

func NewID(id string) (ValidID, error) {

if id == "" {

return ValidID(""), ErrEmptyID

}

return ValidID(id), nil

}

type User struct {

ID ValidID

Email ValidEmail

Name string

}

func CreateUser(idStr, emailStr, name string) (User, error) {

id, err := NewID(idStr)

if err != nil {

return User{}, err

}

email, err := NewEmail(emailStr)

if err != nil {

return User{}, err

}

return User{

ID: id,

Email: email,

Name: name,

}, nil

}

// Ventajas:

// - Garantías a nivel de tipo

// - No puedes crear User con email inválida

// - Sin nil checks innecesariosParte 6: Casos De Estudio Real

6.1 Caso: API Que Devuelve Nil Frecuentemente

El Plan: “Usar nil para indicar ‘no encontrado’”

type UserRepository struct {

db *sql.DB

}

func (r *UserRepository) GetByID(id string) *User {

var user User

err := r.db.QueryRow("SELECT id, email FROM users WHERE id = ?", id).

Scan(&user.ID, &user.Email)

if err == sql.ErrNoRows {

return nil // ← "No encontrado" = nil

}

if err != nil {

return nil // ← "Error" = nil

}

return &user

}

func (r *UserRepository) GetByEmail(email string) *User {

// Mismo patrón

}El Problema (Mes 3):

"¿Por qué tengo nil panics en producción?

Algunos callers no chequean nil.

Otros confunden nil con error.

Otros asumen que devuelve siempre un valor válido."

// Código del caller:

user := repo.GetByID("123")

fmt.Println(user.Email) // ❌ panic si user es nilLa Refactor:

func (r *UserRepository) GetByID(id string) (User, error) {

var user User

err := r.db.QueryRow("SELECT id, email FROM users WHERE id = ?", id).

Scan(&user.ID, &user.Email)

if err == sql.ErrNoRows {

return User{}, ErrUserNotFound

}

if err != nil {

return User{}, err

}

return user, nil

}

// Ahora:

user, err := repo.GetByID("123")

if err == ErrUserNotFound {

fmt.Println("Not found")

} else if err != nil {

fmt.Println("Error:", err)

} else {

fmt.Println("Email:", user.Email) // ✅ Nunca nil

}Lección: “Nil es peligroso para ‘no encontrado’. Usa errores explícitos.”

6.2 Caso: Service Que Acepta Nil “Por Seguridad”

El Plan: “Hacer que todos los parámetros puedan ser nil y validar internamente”

type OrderService struct {

repo *OrderRepository

cache *Cache

}

func (s *OrderService) GetOrder(id *string) (*Order, error) {

// id puede ser nil

if id == nil {

return nil, ErrNilID

}

// cache puede ser nil

if s.cache != nil {

order := s.cache.Get(*id)

if order != nil {

return order, nil

}

}

// repo puede ser nil

if s.repo == nil {

return nil, ErrNilRepository

}

order, err := s.repo.GetByID(*id)

// ...

}El Problema (Mes 2):

"El código está lleno de nil checks.

Es imposible saber qué puede ser nil y qué no.

Cada función es una adivinanza."

// Llamador confundido:

result, err := service.GetOrder(nil)

if err != nil {

// ¿Error porque id es nil? ¿Porque repo es nil?

fmt.Println("Error:", err)

}La Refactor:

type OrderService struct {

repo *OrderRepository // Required

cache *Cache // Optional

}

func NewOrderService(repo *OrderRepository, cache *Cache) (*OrderService, error) {

if repo == nil {

return nil, ErrNilRepository

}

// cache puede ser nil, usamos Null Object si es necesario

if cache == nil {

cache = &NullCache{}

}

return &OrderService{repo: repo, cache: cache}, nil

}

func (s *OrderService) GetOrder(id string) (*Order, error) {

// id es requerido, no pointer

if id == "" {

return nil, ErrEmptyID

}

// cache nunca es nil aquí

order := s.cache.Get(id)

if order != nil {

return order, nil

}

// repo nunca es nil aquí

return s.repo.GetByID(id)

}

// Claro qué es requerido y qué es opcionalLección: “Requiere lo que es necesario. Usa Null Object para lo opcional.”

Parte 7: Mejores Prácticas

7.1 Regla #1: Nunca Devolver Nil Si Puedes Devolver Valor

// ❌ INCORRECTO

func GetConfig() *Config {

if !configExists() {

return nil

}

return &Config{}

}

// ✅ CORRECTO

func GetConfig() (Config, error) {

if !configExists() {

return Config{}, ErrConfigNotFound

}

return Config{}, nil

}7.2 Regla #2: Nil Checks en el Boundary, No Internamente

// ❌ INCORRECTO: Nil checks en todas partes

func ProcessOrder(order *Order) error {

if order == nil {

return ErrNilOrder

}

if err := validate(order); err != nil {

return err

}

if err := save(order); err != nil {

return err

}

return nil

}

func validate(order *Order) error {

if order == nil {

return ErrNilOrder

}

// ...

}

// ✅ CORRECTO: Nil check solo en entry point

func ProcessOrderHandler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

var order Order

if err := json.NewDecoder(r.Body).Decode(&order); err != nil {

http.Error(w, "Invalid request", http.StatusBadRequest)

return

}

if err := service.ProcessOrder(order); err != nil {

http.Error(w, err.Error(), http.StatusInternalServerError)

return

}

w.WriteHeader(http.StatusOK)

}

func (s *Service) ProcessOrder(order Order) error {

// order nunca es nil, no necesita validación

return s.validate(order)

}7.3 Regla #3: Use Values por Defecto, Pointers por Excepción

// ❌ INCORRECTO: Pointers por defecto

type User struct { ... }

type Product struct { ... }

type Order struct { ... }

// Todos pointers = potencial nil en todas partes

// ✅ CORRECTO: Values por defecto

type User struct { ... }

type Product struct { ... }

type Order struct { ... }

// Nil solo cuando semánticamente necesario:

type Optional[T any] struct { ... }

type User struct {

ID string

Email string

Nickname Optional[string] // Puede ser nil

}7.4 Regla #4: Documenta Nil Explícitamente

// ❌ INCORRECTO: Sin documentación

func FindUser(id string) *User {

// ¿Puede devolver nil?

}

// ✅ CORRECTO: Documentado

// FindUser returns a User for the given id, or nil if not found.

// Deprecated: Use FindUserByID which returns an error instead.

func FindUser(id string) *User {

}

// Mejor:

// FindUserByID returns the user with the given id.

// Returns ErrUserNotFound if the user does not exist.

func FindUserByID(id string) (User, error) {

}7.5 Regla #5: Usa Type-Driven Design

// ✅ Hacer imposible estados inválidos

type UserID string

type Email string

func NewUserID(id string) (UserID, error) {

if id == "" {

return UserID(""), ErrEmptyID

}

return UserID(id), nil

}

func NewEmail(e string) (Email, error) {

if !isValidEmail(e) {

return Email(""), ErrInvalidEmail

}

return Email(e), nil

}

type User struct {

ID UserID // Nunca puede ser vacío

Email Email // Siempre válido

}

// Ahora es imposible crear User con ID o Email inválidaParte 8: La Decision Tree

8.1 ¿Debería Esta Función Devolver Nil?

┌─ ¿Es un error válido que suceda?

│

├─ SÍ ──────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ │

│ ├─ ¿Es un error "no encontrado"? │

│ │ ├─ SÍ → return error explícito │

│ │ │ func Get(id) (T, error) │

│ │ │ │

│ │ └─ NO → return error general │

│ │ func Get(id) (T, error) │

│ │ │

│ └─ ¿Qué tipo devolver? │

│ ├─ <128 bytes? → Value │

│ └─ >128 bytes? → Pointer (pero nunca nil) │

│ │

└─ NO ──────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│

├─ ¿El tipo puede existir "vacío"?

│ ├─ SÍ → return value (T{})

│ └─ NO → return error (nunca nil)Parte 9: La Verdad Incómoda

9.1 Go No Resolvió el Problema de Nil

Go decidió no resolver el problema de nil que afectó a Java/C#/JavaScript. En su lugar, Go esperó que los desarrolladores escribieran código cuidado.

Esto funciona si los desarrolladores entienden los patrones. Pero la mayoría no lo hacen.

9.2 La Solución Real

// 1. Nunca devuelvas nil si puedes devolver error

// 2. Usa values en lugar de pointers cuando sea posible

// 3. Valida nil en el boundary, no internamente

// 4. Usa Null Object para interfaces opcionales

// 5. Documenta explícitamente qué puede ser nil

// 6. Usa type-driven design para hacer imposible nil inválido9.3 El Cambio Mental

La mayoría de los desarrolladores piensan: “¿Cómo manejo nil?”

Debería ser: “¿Cómo evito tener que manejar nil?”

Conclusión

Nil en Go es peligroso, pero manejable. No porque Go haya solucionado el problema, sino porque Go obliga a los buenos patrones cuando tratas de evitar nil.

Los equipos que entienden estos patrones escriben código Go seguro, claro, y mantenible.

Los equipos que no entienden terminan con código lleno de nil checks, nil panics, y arquitectura frágil.

La diferencia está en reconocer que nil no es un “valor válido en la mayoría de casos”. Nil es una excepción arquitectónica que debe minimizarse.

Cuando lo haces, Go es tan seguro como cualquier lenguaje moderno.

Tags

Artículos relacionados

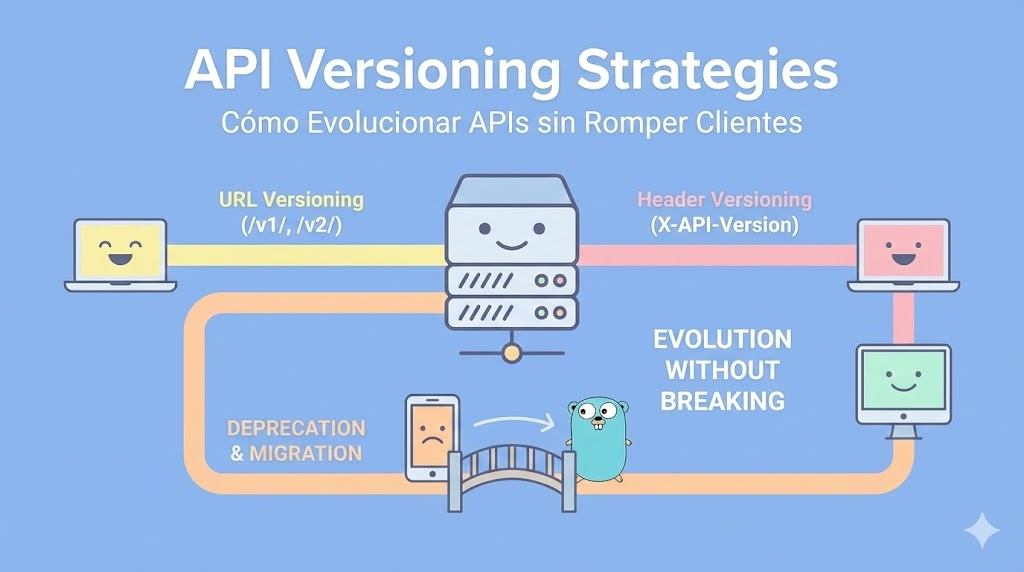

API Versioning Strategies: Cómo Evolucionar APIs sin Romper Clientes

Una guía exhaustiva sobre estrategias de versionado de APIs: URL versioning vs Header versioning, cómo deprecar endpoints sin shock, migration patterns reales, handling de cambios backwards-incompatibles, y decisiones arquitectónicas que importan. Con 50+ ejemplos de código en Go.

Arquitectura de software: Más allá del código

Una guía completa sobre arquitectura de software explicada en lenguaje humano: patrones, organización, estructura y cómo construir sistemas que escalen con tu negocio.

Automatizando tu vida con Go CLI: Guía profesional para crear herramientas de línea de comandos escalables

Una guía exhaustiva y paso a paso sobre cómo crear herramientas CLI escalables con Go 1.25.5: desde lo básico hasta proyectos empresariales complejos con flags, configuración, logging, y ejemplos prácticos para Windows y Linux.