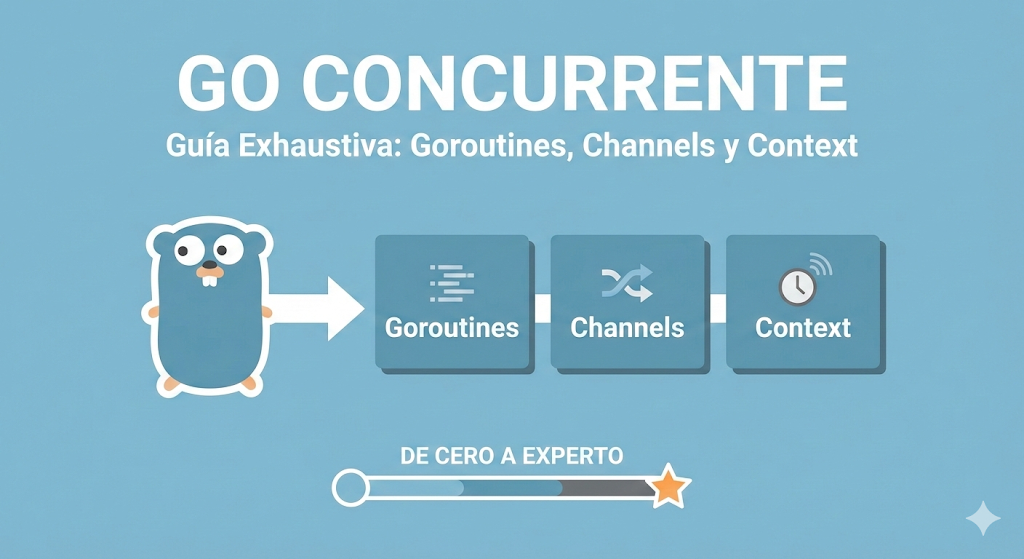

Go Concurrente: Goroutines, Channels y Context - De Cero a Experto

Guía exhaustiva sobre programación concurrente en Go 1.25: goroutines, channels, context, patrones, race conditions, manejo de errores, y arquitectura profesional. Desde principiante absoluto hasta nivel experto con ejemplos prácticos.

Go Concurrente: Goroutines, Channels y Context

De Cero Absoluto a Arquitecto de Sistemas Concurrentes

🎯 Introducción: Por Qué Go Cambió las Reglas del Juego

Déjame ser directo: Go no es solo otro lenguaje de programación. Es una filosofía diferente sobre cómo construir software que escala.

Cuando Rob Pike, Ken Thompson y Robert Griesemer crearon Go en Google en 2007, tenían un problema específico: los sistemas de Google manejaban millones de conexiones simultáneas, y los lenguajes existentes hacían esto innecesariamente complicado.

El problema con otros lenguajes:

- Java: Threads pesados (1MB de stack por thread)

- Python: Global Interpreter Lock (GIL)

- C++: Complejidad brutal, memory management manual

- Node.js: Single-threaded, callback hell

El problema real:

- 10,000 conexiones simultáneas = 10GB de RAM solo en stacks

- Código de concurrencia difícil de escribir y mantener

- Bugs de race conditions casi imposibles de debugearGo resolvió esto con tres innovaciones fundamentales:

- Goroutines: Hilos ultra-ligeros (2KB inicial vs 1MB de threads)

- Channels: Comunicación segura entre goroutines

- Context: Cancelación y timeouts propagados elegantemente

El resultado: Un servidor Go puede manejar 1 millón de goroutines en la misma memoria donde Java manejaría 1,000 threads.

Go 1.25: La Versión Más Madura

Esta guía está actualizada para Go 1.25.5 (Enero 2026), que incluye mejoras significativas:

| Versión | Mejoras Clave |

|---|---|

| Go 1.22 | Loop variable scoping, range-over-int |

| Go 1.23 | Iteradores (iter.Seq), unique package |

| Go 1.24 | Mejoras de rendimiento en scheduler |

| Go 1.25 | sync.OnceValues, optimizaciones de GC, structured concurrency patterns |

Lo Que Esta Guía Cubre

Esta no es una referencia de sintaxis. Es una guía completa para dominar la concurrencia en Go:

✅ Fundamentos de Go - Lo esencial antes de concurrencia

✅ Goroutines - Qué son, cómo funcionan, cuándo usarlas

✅ Channels - El corazón de la comunicación en Go

✅ Select - Multiplexación de operaciones concurrentes

✅ Context - Cancelación, timeouts, y propagación de valores

✅ Patrones - Worker pools, fan-out/fan-in, pipelines

✅ Race Conditions - Detectarlas, prevenirlas, debugearlas

✅ Sync Package - Mutex, WaitGroup, Once, Pool

✅ Go 1.23-1.25 - Iteradores, unique, nuevas APIs

✅ Errores Comunes - Y cómo evitarlos

✅ Arquitectura - Diseño de sistemas concurrentes reales

Prerequisitos

- Conocimiento básico de programación (cualquier lenguaje)

- Terminal/línea de comandos

- Go 1.25+ instalado (usaremos features modernos)

Si nunca has usado Go, no te preocupes. Empezamos desde cero.

🏗️ Parte 1: Fundamentos de Go - Lo Esencial

Antes de hablar de concurrencia, necesitas entender Go. Esta sección es un curso acelerado de lo esencial.

Instalación y Setup (Go 1.25+)

# Linux/Mac

wget https://go.dev/dl/go1.25.5.linux-amd64.tar.gz

sudo tar -C /usr/local -xzf go1.25.5.linux-amd64.tar.gz

export PATH=$PATH:/usr/local/go/bin

# Verificar instalación

go version

# go version go1.25.5 linux/amd64Tu Primer Programa Go

Crea un archivo main.go:

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

fmt.Println("¡Hola, Go!")

}Ejecutar:

go run main.go

# ¡Hola, Go!Anatomía de un Programa Go

package main // Todo archivo Go pertenece a un package

// 'main' es especial: es el punto de entrada

import "fmt" // Importamos packages

// 'fmt' es para formateo e impresión

func main() { // La función main() es donde empieza la ejecución

// Tu código aquí

}Variables y Tipos Básicos

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Declaración explícita

var nombre string = "Carlos"

var edad int = 30

var activo bool = true

// Declaración corta (inferencia de tipos) - MÁS COMÚN

apellido := "García" // Go infiere que es string

altura := 1.75 // Go infiere que es float64

// Múltiples variables

x, y, z := 1, 2, 3

// Constantes

const PI = 3.14159

const MaxConexiones = 100

fmt.Printf("Nombre: %s %s\n", nombre, apellido)

fmt.Printf("Edad: %d, Altura: %.2f\n", edad, altura)

fmt.Printf("Activo: %t\n", activo)

}Tipos básicos en Go:

// Enteros

int, int8, int16, int32, int64

uint, uint8, uint16, uint32, uint64

// Flotantes

float32, float64

// Otros

bool // true o false

string // cadenas de texto (inmutables)

byte // alias de uint8

rune // alias de int32 (para Unicode)Funciones

package main

import "fmt"

// Función simple

func saludar(nombre string) {

fmt.Printf("Hola, %s!\n", nombre)

}

// Función con retorno

func sumar(a, b int) int {

return a + b

}

// Múltiples retornos (MUY COMÚN en Go)

func dividir(a, b float64) (float64, error) {

if b == 0 {

return 0, fmt.Errorf("división por cero")

}

return a / b, nil

}

// Retornos nombrados

func rectangulo(ancho, alto float64) (area, perimetro float64) {

area = ancho * alto

perimetro = 2 * (ancho + alto)

return // return "desnudo" - retorna las variables nombradas

}

func main() {

saludar("María")

resultado := sumar(5, 3)

fmt.Println("5 + 3 =", resultado)

// Manejo de errores (patrón fundamental en Go)

cociente, err := dividir(10, 2)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println("Error:", err)

return

}

fmt.Println("10 / 2 =", cociente)

a, p := rectangulo(5, 3)

fmt.Printf("Área: %.2f, Perímetro: %.2f\n", a, p)

}El Patrón de Manejo de Errores en Go

Go no tiene excepciones. Usa retornos múltiples con errores explícitos:

// ❌ NO existe en Go

try {

resultado = operacionRiesgosa()

} catch (error) {

// manejar error

}

// ✅ Así se hace en Go

resultado, err := operacionRiesgosa()

if err != nil {

// manejar error

return err // o log, o recuperar

}

// usar resultadoEste patrón te obliga a pensar en los errores en cada paso. Es verbose, pero te salva de bugs silenciosos.

Slices y Maps

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// SLICES (arreglos dinámicos)

// Crear un slice vacío

var numeros []int

numeros = append(numeros, 1, 2, 3)

// Crear con valores iniciales

frutas := []string{"manzana", "banana", "cereza"}

// Crear con capacidad (más eficiente)

datos := make([]int, 0, 100) // len=0, cap=100

// Acceso y modificación

fmt.Println(frutas[0]) // "manzana"

frutas[1] = "blueberry" // modificar

// Slicing

primerosDos := frutas[0:2] // ["manzana", "blueberry"]

// Iterar

for i, fruta := range frutas {

fmt.Printf("%d: %s\n", i, fruta)

}

// MAPS (diccionarios)

// Crear un map

edades := make(map[string]int)

edades["Carlos"] = 30

edades["María"] = 25

// Crear con valores iniciales

capitales := map[string]string{

"México": "CDMX",

"Argentina": "Buenos Aires",

"España": "Madrid",

}

// Acceso

edad := edades["Carlos"]

fmt.Println("Carlos tiene", edad, "años")

// Verificar si existe

capital, existe := capitales["Chile"]

if !existe {

fmt.Println("Chile no está en el mapa")

}

// Eliminar

delete(edades, "Carlos")

// Iterar

for pais, capital := range capitales {

fmt.Printf("%s -> %s\n", pais, capital)

}

}Structs (Estructuras)

package main

import "fmt"

// Definir una estructura

type Persona struct {

Nombre string

Edad int

Email string

Activo bool

}

// Método asociado a Persona

func (p Persona) Saludar() string {

return fmt.Sprintf("Hola, soy %s y tengo %d años", p.Nombre, p.Edad)

}

// Método que modifica (necesita puntero)

func (p *Persona) CumplirAnios() {

p.Edad++

}

func main() {

// Crear una instancia

carlos := Persona{

Nombre: "Carlos",

Edad: 30,

Email: "carlos@email.com",

Activo: true,

}

// Acceder a campos

fmt.Println(carlos.Nombre)

// Llamar métodos

fmt.Println(carlos.Saludar())

carlos.CumplirAnios()

fmt.Println("Después del cumpleaños:", carlos.Edad)

// Punteros

ptr := &carlos // puntero a carlos

ptr.Nombre = "Carlos García" // Go auto-dereferencia

fmt.Println(carlos.Nombre) // "Carlos García"

}Interfaces

Las interfaces en Go son implícitas. No declaras que un tipo implementa una interface; simplemente lo hace si tiene los métodos correctos.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"math"

)

// Definir una interface

type Figura interface {

Area() float64

Perimetro() float64

}

// Rectángulo implementa Figura (implícitamente)

type Rectangulo struct {

Ancho, Alto float64

}

func (r Rectangulo) Area() float64 {

return r.Ancho * r.Alto

}

func (r Rectangulo) Perimetro() float64 {

return 2 * (r.Ancho + r.Alto)

}

// Círculo también implementa Figura

type Circulo struct {

Radio float64

}

func (c Circulo) Area() float64 {

return math.Pi * c.Radio * c.Radio

}

func (c Circulo) Perimetro() float64 {

return 2 * math.Pi * c.Radio

}

// Función que acepta cualquier Figura

func imprimirInfo(f Figura) {

fmt.Printf("Área: %.2f, Perímetro: %.2f\n", f.Area(), f.Perimetro())

}

func main() {

rect := Rectangulo{Ancho: 5, Alto: 3}

circ := Circulo{Radio: 2.5}

// Ambos pueden pasarse a imprimirInfo

imprimirInfo(rect)

imprimirInfo(circ)

// Slice de interfaces

figuras := []Figura{rect, circ}

for _, f := range figuras {

imprimirInfo(f)

}

}La Interface Vacía: any (antes interface{})

package main

import "fmt"

func imprimir(valor any) {

fmt.Printf("Tipo: %T, Valor: %v\n", valor, valor)

}

func main() {

imprimir(42)

imprimir("hola")

imprimir(3.14)

imprimir(true)

// Type assertion

var x any = "texto"

// Forma insegura (panic si falla)

s := x.(string)

fmt.Println(s)

// Forma segura

if s, ok := x.(string); ok {

fmt.Println("Es string:", s)

}

// Type switch

switch v := x.(type) {

case string:

fmt.Println("Es string:", v)

case int:

fmt.Println("Es int:", v)

default:

fmt.Println("Tipo desconocido")

}

}📊 Resumen de la Parte 1

Ahora conoces los fundamentos de Go:

| Concepto | Go | Notas |

|---|---|---|

| Variables | x := valor | Inferencia de tipos |

| Funciones | func nombre(params) retorno | Múltiples retornos |

| Errores | resultado, err := fn() | Sin excepciones |

| Slices | []tipo | Arreglos dinámicos |

| Maps | map[key]value | Diccionarios |

| Structs | type Nombre struct{} | Con métodos |

| Interfaces | Implícitas | Duck typing |

flowchart TD

subgraph Fundamentos["Fundamentos de Go"]

A[Variables y Tipos] --> B[Funciones]

B --> C[Manejo de Errores]

C --> D[Slices y Maps]

D --> E[Structs]

E --> F[Interfaces]

end

F --> G[🚀 Listo para Concurrencia]

style G fill:#10b981,color:#fffCon estos fundamentos, estás listo para el plato fuerte: Goroutines y Concurrencia.

🚀 Parte 2: Goroutines - Concurrencia Ligera

¿Qué es una Goroutine?

Una goroutine es una función que se ejecuta de forma concurrente con otras goroutines. Piensa en ella como un “hilo ultra-ligero” gestionado por el runtime de Go, no por el sistema operativo.

Analogía del Restaurante:

Imagina un restaurante:

MODELO TRADICIONAL (Threads del SO):

- Cada cliente que llega = 1 mesero dedicado

- 1000 clientes = 1000 meseros

- Cada mesero ocupa espacio, come, cobra sueldo

- El restaurante colapsa rápido

MODELO GO (Goroutines):

- 1000 clientes llegan

- Solo 4 meseros (= número de CPUs)

- Los meseros atienden tareas de todos los clientes

- Mientras un cliente piensa qué ordenar, el mesero atiende a otro

- El restaurante escala sin problemasComparación: Threads vs Goroutines

| Característica | Thread del SO | Goroutine |

|---|---|---|

| Memoria inicial | ~1MB | ~2KB |

| Creación | Costosa (syscall) | Barata (función) |

| Cambio contexto | Lento (kernel) | Rápido (userspace) |

| Cantidad práctica | ~1,000s | ~1,000,000s |

| Gestión | Sistema operativo | Runtime de Go |

Tu Primera Goroutine

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func saludar(nombre string) {

for i := 0; i < 3; i++ {

fmt.Printf("Hola %s! (iteración %d)\n", nombre, i)

time.Sleep(100 * time.Millisecond)

}

}

func main() {

// EJECUCIÓN SECUENCIAL (sin goroutines)

fmt.Println("=== Secuencial ===")

saludar("Carlos")

saludar("María")

// EJECUCIÓN CONCURRENTE (con goroutines)

fmt.Println("\n=== Concurrente ===")

go saludar("Carlos") // 'go' lanza una goroutine

go saludar("María") // otra goroutine

// ¡PROBLEMA! El programa termina antes de que las goroutines terminen

time.Sleep(500 * time.Millisecond) // hack temporal

fmt.Println("Fin del programa")

}Salida típica concurrente (orden no garantizado):

=== Secuencial ===

Hola Carlos! (iteración 0)

Hola Carlos! (iteración 1)

Hola Carlos! (iteración 2)

Hola María! (iteración 0)

Hola María! (iteración 1)

Hola María! (iteración 2)

=== Concurrente ===

Hola Carlos! (iteración 0)

Hola María! (iteración 0)

Hola María! (iteración 1)

Hola Carlos! (iteración 1)

Hola Carlos! (iteración 2)

Hola María! (iteración 2)

Fin del programaEl Problema del Main que Termina

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

go fmt.Println("Hola desde goroutine")

// El programa termina aquí ANTES de que la goroutine ejecute

}Resultado: Probablemente no imprime nada. El main() es una goroutine también, y cuando termina, el programa termina, matando todas las goroutines activas.

Solución Correcta: sync.WaitGroup

package main

import (

"fmt"

"sync"

"time"

)

func trabajador(id int, wg *sync.WaitGroup) {

defer wg.Done() // Notifica que terminó (SIEMPRE con defer)

fmt.Printf("Trabajador %d: iniciando\n", id)

time.Sleep(time.Second)

fmt.Printf("Trabajador %d: terminado\n", id)

}

func main() {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

for i := 1; i <= 5; i++ {

wg.Add(1) // Incrementa el contador ANTES de lanzar

go trabajador(i, &wg) // Pasa por puntero

}

fmt.Println("Esperando a que terminen los trabajadores...")

wg.Wait() // Bloquea hasta que el contador llegue a 0

fmt.Println("Todos los trabajadores terminaron")

}Flujo del WaitGroup:

sequenceDiagram

participant M as Main

participant WG as WaitGroup

participant W1 as Worker 1

participant W2 as Worker 2

M->>WG: Add(1)

M->>W1: go trabajador(1)

M->>WG: Add(1)

M->>W2: go trabajador(2)

M->>WG: Wait() [bloquea]

W1->>W1: Trabaja...

W2->>W2: Trabaja...

W1->>WG: Done()

W2->>WG: Done()

WG->>M: Continúa (contador = 0)Errores Comunes con WaitGroup

// ❌ ERROR 1: Add() dentro de la goroutine (race condition)

for i := 0; i < 5; i++ {

go func() {

wg.Add(1) // ¡INCORRECTO! Puede que Wait() ya haya pasado

defer wg.Done()

// trabajo

}()

}

// ✅ CORRECTO: Add() antes de lanzar

for i := 0; i < 5; i++ {

wg.Add(1)

go func() {

defer wg.Done()

// trabajo

}()

}

// ❌ ERROR 2: Pasar WaitGroup por valor

go trabajador(i, wg) // Copia el WaitGroup - Done() no afecta al original

// ✅ CORRECTO: Pasar por puntero

go trabajador(i, &wg)

// ❌ ERROR 3: Olvidar Done()

go func() {

// trabajo

// wg.Done() olvidado - Wait() bloquea para siempre

}()

// ✅ CORRECTO: Usar defer

go func() {

defer wg.Done() // SIEMPRE se ejecuta, incluso con panic

// trabajo

}()Goroutines Anónimas y Closures

package main

import (

"fmt"

"sync"

)

func main() {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

// ❌ ERROR CLÁSICO: Closure captura variable del loop

fmt.Println("=== Incorrecto ===")

for i := 0; i < 3; i++ {

wg.Add(1)

go func() {

defer wg.Done()

fmt.Println(i) // Probablemente imprime 3, 3, 3

}()

}

wg.Wait()

// ✅ CORRECTO: Pasar como parámetro

fmt.Println("\n=== Correcto (parámetro) ===")

for i := 0; i < 3; i++ {

wg.Add(1)

go func(n int) { // n es una copia de i

defer wg.Done()

fmt.Println(n)

}(i) // Pasa i como argumento

}

wg.Wait()

// ✅ CORRECTO en Go 1.22+: Loop variable scoping

fmt.Println("\n=== Correcto (Go 1.22+) ===")

for i := 0; i < 3; i++ {

wg.Add(1)

go func() {

defer wg.Done()

fmt.Println(i) // Go 1.22+ captura correctamente

}()

}

wg.Wait()

}Nota Go 1.22+: A partir de Go 1.22, las variables de loop tienen scope por iteración, eliminando este bug clásico. En Go 1.25 esto es comportamiento estándar y ya no necesitas workarounds.

¿Cuántas Goroutines Puedo Lanzar?

package main

import (

"fmt"

"runtime"

"sync"

"time"

)

func main() {

// Número de CPUs disponibles

fmt.Println("CPUs:", runtime.NumCPU())

// Crear MUCHAS goroutines

var wg sync.WaitGroup

numGoroutines := 100_000

start := time.Now()

for i := 0; i < numGoroutines; i++ {

wg.Add(1)

go func(id int) {

defer wg.Done()

// Simular algo de trabajo

time.Sleep(10 * time.Millisecond)

}(i)

}

// ¿Cuántas goroutines hay activas?

fmt.Printf("Goroutines activas: %d\n", runtime.NumGoroutine())

wg.Wait()

fmt.Printf("Tiempo total: %v\n", time.Since(start))

}Resultado típico:

CPUs: 8

Goroutines activas: 100001

Tiempo total: ~50ms (no 1000 segundos)100,000 goroutines ejecutadas en paralelo con 8 CPUs en ~50ms. Eso es el poder de Go.

Cómo Funciona Internamente: El Scheduler de Go

Go usa un modelo M:N (M goroutines sobre N threads del SO):

flowchart TB

subgraph Goroutines["Goroutines (miles/millones)"]

G1[G1]

G2[G2]

G3[G3]

G4[G4]

G5[G5]

G6[G6]

end

subgraph Processors["Procesadores Lógicos (P)"]

P1[P1]

P2[P2]

end

subgraph Threads["Threads del SO (M)"]

M1[M1]

M2[M2]

M3[M3]

end

subgraph CPU["CPUs Físicos"]

C1[Core 1]

C2[Core 2]

end

G1 --> P1

G2 --> P1

G3 --> P1

G4 --> P2

G5 --> P2

G6 --> P2

P1 --> M1

P2 --> M2

M1 --> C1

M2 --> C2Conceptos clave:

- G (Goroutine): Tu código concurrente

- P (Processor): Cola de goroutines listas para ejecutar

- M (Machine): Thread del sistema operativo

El scheduler de Go:

- Asigna goroutines a Ps

- Cada P se ejecuta en un M

- Cuando una goroutine bloquea (I/O, syscall), el scheduler mueve otras goroutines a otro M

- Work stealing: Si un P no tiene trabajo, roba goroutines de otro P

GOMAXPROCS: Controlando el Paralelismo

package main

import (

"fmt"

"runtime"

)

func main() {

// Ver el valor actual

fmt.Println("GOMAXPROCS actual:", runtime.GOMAXPROCS(0))

// Establecer un nuevo valor (retorna el anterior)

anterior := runtime.GOMAXPROCS(4)

fmt.Println("GOMAXPROCS anterior:", anterior)

fmt.Println("GOMAXPROCS nuevo:", runtime.GOMAXPROCS(0))

// Por defecto, GOMAXPROCS = número de CPUs

runtime.GOMAXPROCS(runtime.NumCPU())

}¿Cuándo modificar GOMAXPROCS?

- Casi nunca. El valor por defecto es óptimo para la mayoría de casos.

- En containers: Usa

runtime/cgrouppara detectar límites correctamente - Para testing:

GOMAXPROCS=1serializa goroutines (útil para debugging)

Ejemplo Práctico: Procesamiento de Imágenes Concurrente

package main

import (

"fmt"

"sync"

"time"

)

type Imagen struct {

ID int

Filename string

}

func procesarImagen(img Imagen) {

// Simula procesamiento (resize, filtros, etc.)

time.Sleep(100 * time.Millisecond)

fmt.Printf("Imagen %d (%s) procesada\n", img.ID, img.Filename)

}

func main() {

imagenes := []Imagen{

{1, "foto1.jpg"},

{2, "foto2.jpg"},

{3, "foto3.jpg"},

{4, "foto4.jpg"},

{5, "foto5.jpg"},

}

// SECUENCIAL

fmt.Println("=== Procesamiento Secuencial ===")

start := time.Now()

for _, img := range imagenes {

procesarImagen(img)

}

fmt.Printf("Tiempo secuencial: %v\n\n", time.Since(start))

// CONCURRENTE

fmt.Println("=== Procesamiento Concurrente ===")

start = time.Now()

var wg sync.WaitGroup

for _, img := range imagenes {

wg.Add(1)

go func(img Imagen) {

defer wg.Done()

procesarImagen(img)

}(img)

}

wg.Wait()

fmt.Printf("Tiempo concurrente: %v\n", time.Since(start))

}Salida típica:

=== Procesamiento Secuencial ===

Imagen 1 (foto1.jpg) procesada

Imagen 2 (foto2.jpg) procesada

Imagen 3 (foto3.jpg) procesada

Imagen 4 (foto4.jpg) procesada

Imagen 5 (foto5.jpg) procesada

Tiempo secuencial: 500ms

=== Procesamiento Concurrente ===

Imagen 3 (foto3.jpg) procesada

Imagen 1 (foto1.jpg) procesada

Imagen 5 (foto5.jpg) procesada

Imagen 2 (foto2.jpg) procesada

Imagen 4 (foto4.jpg) procesada

Tiempo concurrente: 100ms¡5x más rápido con concurrencia!

📊 Resumen de la Parte 2

| Concepto | Sintaxis | Uso |

|---|---|---|

| Lanzar goroutine | go funcion() | Ejecutar concurrentemente |

| Esperar goroutines | sync.WaitGroup | Sincronización |

| Goroutine anónima | go func() { }() | Código inline |

| CPUs disponibles | runtime.NumCPU() | Información del sistema |

| Paralelismo | runtime.GOMAXPROCS(n) | Controlar threads |

flowchart LR

subgraph Goroutines["Lo que aprendiste"]

A[go keyword] --> B[WaitGroup]

B --> C[Closures]

C --> D[Scheduler]

D --> E[GOMAXPROCS]

end

E --> F[🔌 Listo para Channels]

style F fill:#3b82f6,color:#fffLas goroutines son poderosas, pero tienen un problema: ¿cómo se comunican entre sí?

La respuesta: Channels.

🔌 Parte 3: Channels - Comunicación Entre Goroutines

El Mantra de Go

“No comuniques compartiendo memoria; comparte memoria comunicando.”

— Rob Pike, co-creador de Go

Esta frase define la filosofía de Go. En lugar de tener datos compartidos protegidos con locks (como en Java/C++), Go prefiere que las goroutines se envíen datos unas a otras a través de channels.

¿Qué es un Channel?

Un channel es un conducto tipado a través del cual puedes enviar y recibir valores. Es como una tubería: un lado mete datos, el otro lado los saca.

flowchart LR

G1[Goroutine 1] -->|envía dato| CH((Channel))

CH -->|recibe dato| G2[Goroutine 2]

style CH fill:#3b82f6,color:#fffAnalogía de la Panadería:

Imagina una panadería con un mostrador:

- El panadero (goroutine 1) hornea pan y lo pone en el mostrador

- El cliente (goroutine 2) toma pan del mostrador

- El mostrador ES el channel

Reglas del mostrador:

- Si no hay pan, el cliente espera

- Si el mostrador está lleno, el panadero espera

- No hay conflictos: uno pone, otro tomaCrear y Usar Channels

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Crear un channel de enteros

ch := make(chan int)

// Enviar en una goroutine (porque el channel sin buffer bloquea)

go func() {

ch <- 42 // Enviar valor al channel

}()

// Recibir del channel

valor := <-ch // Recibir valor del channel

fmt.Println("Recibido:", valor)

}Sintaxis de Channels

// Crear channels

ch := make(chan int) // channel sin buffer (unbuffered)

ch := make(chan string, 10) // channel con buffer de 10 elementos

// Operaciones

ch <- valor // Enviar al channel (bloquea si está lleno)

valor := <-ch // Recibir del channel (bloquea si está vacío)

valor, ok := <-ch // ok=false si channel cerrado y vacío

// Cerrar channel (solo el sender debería cerrar)

close(ch)

// Tipos direccionales

func enviar(ch chan<- int) {} // Solo puede enviar

func recibir(ch <-chan int) {} // Solo puede recibirChannels Sin Buffer (Unbuffered)

Un channel sin buffer sincroniza las goroutines: el envío bloquea hasta que alguien reciba, y viceversa.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func main() {

ch := make(chan string) // Sin buffer

go func() {

fmt.Println("Goroutine: preparando mensaje...")

time.Sleep(2 * time.Second)

ch <- "¡Hola desde la goroutine!" // BLOQUEA hasta que main reciba

fmt.Println("Goroutine: mensaje enviado")

}()

fmt.Println("Main: esperando mensaje...")

msg := <-ch // BLOQUEA hasta que la goroutine envíe

fmt.Println("Main: recibido:", msg)

}Salida:

Main: esperando mensaje...

Goroutine: preparando mensaje...

Main: recibido: ¡Hola desde la goroutine!

Goroutine: mensaje enviadosequenceDiagram

participant M as Main

participant CH as Channel

participant G as Goroutine

G->>G: Preparando (2s)

M->>CH: <-ch [BLOQUEA]

G->>CH: ch <- msg

CH->>M: msg recibido

Note over M,G: Ambos continúanChannels Con Buffer

Un channel con buffer puede almacenar N elementos. Solo bloquea cuando está lleno (al enviar) o vacío (al recibir).

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Buffer de 3 elementos

ch := make(chan int, 3)

// Podemos enviar 3 veces sin bloquear

ch <- 1

ch <- 2

ch <- 3

// ch <- 4 // ¡Esto bloquearía! (buffer lleno, nadie recibe)

fmt.Println(<-ch) // 1

fmt.Println(<-ch) // 2

fmt.Println(<-ch) // 3

}¿Cuándo usar buffer?

| Sin Buffer | Con Buffer |

|---|---|

| Sincronización fuerte | Desacoplar producer/consumer |

| Handoff directo | Absorber ráfagas de trabajo |

| Más simple de razonar | Más throughput |

Cerrar Channels

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

ch := make(chan int, 3)

// Enviar algunos valores

ch <- 1

ch <- 2

ch <- 3

close(ch) // Cerrar el channel

// Recibir de channel cerrado

fmt.Println(<-ch) // 1

fmt.Println(<-ch) // 2

fmt.Println(<-ch) // 3

fmt.Println(<-ch) // 0 (valor zero del tipo)

// Detectar si está cerrado

val, ok := <-ch

fmt.Printf("Valor: %d, Abierto: %t\n", val, ok) // Valor: 0, Abierto: false

}Reglas importantes de close():

// ✅ El SENDER cierra el channel

close(ch)

// ❌ NUNCA cierres un channel desde el receiver

// ❌ NUNCA cierres un channel dos veces (panic)

// ❌ NUNCA envíes a un channel cerrado (panic)

// Enviar a channel cerrado = PANIC

ch := make(chan int)

close(ch)

ch <- 1 // panic: send on closed channelIterar sobre Channels con Range

package main

import "fmt"

func generador(n int) <-chan int {

ch := make(chan int)

go func() {

for i := 0; i < n; i++ {

ch <- i

}

close(ch) // ¡Importante! Permite que range termine

}()

return ch

}

func main() {

// Range itera hasta que el channel se cierra

for num := range generador(5) {

fmt.Println(num)

}

fmt.Println("Generador agotado")

}Salida:

0

1

2

3

4

Generador agotadoChannels Direccionales

Puedes restringir un channel a solo-envío o solo-recepción. Esto hace el código más seguro y auto-documentado.

package main

import "fmt"

// Esta función SOLO puede enviar al channel

func productor(ch chan<- int) {

for i := 0; i < 5; i++ {

ch <- i

}

close(ch)

}

// Esta función SOLO puede recibir del channel

func consumidor(ch <-chan int) {

for num := range ch {

fmt.Println("Recibido:", num)

}

}

func main() {

ch := make(chan int) // Bidireccional

go productor(ch) // Se convierte a chan<- int automáticamente

consumidor(ch) // Se convierte a <-chan int automáticamente

}Ejemplo Práctico: Pipeline de Procesamiento

Un pipeline es una cadena de etapas donde cada etapa es una goroutine que procesa datos y los pasa a la siguiente.

package main

import "fmt"

// Etapa 1: Genera números

func generar(nums ...int) <-chan int {

out := make(chan int)

go func() {

for _, n := range nums {

out <- n

}

close(out)

}()

return out

}

// Etapa 2: Eleva al cuadrado

func cuadrado(in <-chan int) <-chan int {

out := make(chan int)

go func() {

for n := range in {

out <- n * n

}

close(out)

}()

return out

}

// Etapa 3: Suma todos

func sumar(in <-chan int) <-chan int {

out := make(chan int)

go func() {

total := 0

for n := range in {

total += n

}

out <- total

close(out)

}()

return out

}

func main() {

// Pipeline: generar -> cuadrado -> sumar

// 1,2,3,4 -> 1,4,9,16 -> 30

resultado := sumar(cuadrado(generar(1, 2, 3, 4)))

fmt.Println("Resultado:", <-resultado) // 30

}flowchart LR

A[generar<br>1,2,3,4] --> B[cuadrado<br>1,4,9,16]

B --> C[sumar<br>30]

style A fill:#22c55e,color:#fff

style B fill:#3b82f6,color:#fff

style C fill:#8b5cf6,color:#fffErrores Comunes con Channels

// ❌ ERROR 1: Deadlock - enviar sin receptor

func main() {

ch := make(chan int)

ch <- 1 // DEADLOCK: nadie puede recibir

}

// ❌ ERROR 2: Deadlock - recibir sin emisor

func main() {

ch := make(chan int)

<-ch // DEADLOCK: nadie enviará

}

// ❌ ERROR 3: Channel nil

func main() {

var ch chan int // nil

ch <- 1 // BLOQUEA PARA SIEMPRE

<-ch // BLOQUEA PARA SIEMPRE

}

// ✅ CORRECTO: Siempre inicializa

func main() {

ch := make(chan int)

// usar ch

}

// ❌ ERROR 4: Olvidar cerrar en range

func main() {

ch := make(chan int)

go func() {

ch <- 1

ch <- 2

// olvidó close(ch)

}()

for n := range ch { // DEADLOCK después de recibir 1 y 2

fmt.Println(n)

}

}Detectar Deadlock

Go detecta deadlocks globales automáticamente:

package main

func main() {

ch := make(chan int)

ch <- 1

}Salida:

fatal error: all goroutines are asleep - deadlock!

goroutine 1 [chan send]:

main.main()

/path/main.go:5 +0x...Pero no detecta deadlocks parciales:

func main() {

ch := make(chan int)

go func() {

ch <- 1

ch <- 2 // Bloquea aquí si main solo lee una vez

}()

fmt.Println(<-ch) // Lee 1

// La goroutine queda bloqueada intentando enviar 2

// El programa termina sin error

}📊 Resumen de la Parte 3

| Operación | Sintaxis | Comportamiento |

|---|---|---|

| Crear unbuffered | make(chan T) | Bloquea hasta match |

| Crear buffered | make(chan T, n) | Buffer de n elementos |

| Enviar | ch <- v | Bloquea si lleno/unbuffered |

| Recibir | v := <-ch | Bloquea si vacío |

| Cerrar | close(ch) | Solo el sender |

| Iterar | for v := range ch | Hasta que cierre |

flowchart TD

subgraph Channels["Lo que aprendiste"]

A[make chan] --> B[Enviar/Recibir]

B --> C[Buffered vs Unbuffered]

C --> D[close y range]

D --> E[Direccionales]

E --> F[Pipelines]

end

F --> G[⚡ Listo para Select]

style G fill:#f59e0b,color:#fffLos channels son poderosos, pero ¿qué pasa cuando necesitas escuchar múltiples channels a la vez?

La respuesta: Select.

⚡ Parte 4: Select - Multiplexando Channels

¿Qué es Select?

select es como un switch pero para operaciones de channels. Permite esperar en múltiples channels simultáneamente y ejecutar el caso que esté listo primero.

Analogía del Aeropuerto:

Imagina que estás en un aeropuerto esperando tu vuelo:

- Puerta A: Vuelo a Madrid

- Puerta B: Vuelo a París

- Puerta C: Anuncio de retrasos

Un 'select' es como tener ojos en las 3 puertas:

- Reaccionas al PRIMERO que tenga actividad

- No te quedas "pegado" esperando solo una puertaSintaxis Básica

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func main() {

ch1 := make(chan string)

ch2 := make(chan string)

go func() {

time.Sleep(1 * time.Second)

ch1 <- "mensaje de canal 1"

}()

go func() {

time.Sleep(2 * time.Second)

ch2 <- "mensaje de canal 2"

}()

// Select espera en ambos channels

for i := 0; i < 2; i++ {

select {

case msg1 := <-ch1:

fmt.Println("Recibido de ch1:", msg1)

case msg2 := <-ch2:

fmt.Println("Recibido de ch2:", msg2)

}

}

}Salida:

Recibido de ch1: mensaje de canal 1

Recibido de ch2: mensaje de canal 2Comportamiento de Select

select {

case <-ch1:

// Se ejecuta si ch1 tiene datos

case ch2 <- valor:

// Se ejecuta si ch2 puede recibir

case val := <-ch3:

// Recibe y asigna

default:

// Se ejecuta si ningún otro caso está listo (non-blocking)

}Reglas:

- Si ningún caso está listo → bloquea (sin default)

- Si un caso está listo → lo ejecuta

- Si múltiples casos están listos → elige uno al azar

- Si hay default y ningún caso listo → ejecuta default

Select Non-Blocking con Default

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

ch := make(chan int)

// Intenta recibir sin bloquear

select {

case val := <-ch:

fmt.Println("Recibido:", val)

default:

fmt.Println("No hay datos disponibles")

}

// Intenta enviar sin bloquear

select {

case ch <- 42:

fmt.Println("Enviado: 42")

default:

fmt.Println("No se pudo enviar (nadie escucha)")

}

}Salida:

No hay datos disponibles

No se pudo enviar (nadie escucha)Timeout con Select

Uno de los usos más comunes de select es implementar timeouts:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func operacionLenta() <-chan string {

ch := make(chan string)

go func() {

time.Sleep(3 * time.Second) // Simula operación lenta

ch <- "resultado"

}()

return ch

}

func main() {

resultado := operacionLenta()

select {

case res := <-resultado:

fmt.Println("Éxito:", res)

case <-time.After(2 * time.Second):

fmt.Println("Timeout: la operación tardó demasiado")

}

}Salida:

Timeout: la operación tardó demasiadosequenceDiagram

participant M as Main

participant OP as operacionLenta

participant T as Timer

M->>OP: Inicia operación

M->>T: Inicia timer (2s)

Note over OP: Trabajando...

T->>M: ¡Timeout!

M->>M: Ejecuta case timeout

Note over OP: Sigue trabajando (ignorado)Ticker y Timer

Go proporciona time.Ticker y time.Timer que se integran con select:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func main() {

// Timer: dispara UNA vez después de la duración

timer := time.NewTimer(2 * time.Second)

// Ticker: dispara REPETIDAMENTE cada duración

ticker := time.NewTicker(500 * time.Millisecond)

done := make(chan bool)

go func() {

time.Sleep(2500 * time.Millisecond)

done <- true

}()

for {

select {

case <-ticker.C:

fmt.Println("Tick")

case <-timer.C:

fmt.Println("Timer disparado!")

case <-done:

ticker.Stop()

fmt.Println("Terminando")

return

}

}

}Salida:

Tick

Tick

Tick

Tick

Timer disparado!

Tick

TerminandoSelect Infinito con For

El patrón más común es for + select:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func main() {

datos := make(chan int)

salir := make(chan bool)

// Productor

go func() {

for i := 1; i <= 5; i++ {

datos <- i

time.Sleep(500 * time.Millisecond)

}

salir <- true

}()

// Consumidor con select infinito

for {

select {

case d := <-datos:

fmt.Println("Dato recibido:", d)

case <-salir:

fmt.Println("Señal de salida recibida")

return

}

}

}Caso Especial: nil Channels en Select

Un channel nil en select se ignora (nunca está listo):

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

ch1 := make(chan int)

var ch2 chan int // nil

go func() {

ch1 <- 1

}()

select {

case v := <-ch1:

fmt.Println("ch1:", v)

case v := <-ch2:

// NUNCA se ejecuta (ch2 es nil)

fmt.Println("ch2:", v)

}

}Uso práctico: Puedes “desactivar” un channel estableciéndolo a nil:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func main() {

ch1 := make(chan int)

ch2 := make(chan int)

go func() {

for i := 0; i < 3; i++ {

time.Sleep(100 * time.Millisecond)

ch1 <- i

}

close(ch1)

}()

go func() {

for i := 10; i < 13; i++ {

time.Sleep(150 * time.Millisecond)

ch2 <- i

}

close(ch2)

}()

for ch1 != nil || ch2 != nil {

select {

case v, ok := <-ch1:

if !ok {

ch1 = nil // Desactivar este case

fmt.Println("ch1 cerrado")

continue

}

fmt.Println("ch1:", v)

case v, ok := <-ch2:

if !ok {

ch2 = nil // Desactivar este case

fmt.Println("ch2 cerrado")

continue

}

fmt.Println("ch2:", v)

}

}

fmt.Println("Ambos channels cerrados")

}Ejemplo Práctico: Worker con Graceful Shutdown

package main

import (

"fmt"

"os"

"os/signal"

"syscall"

"time"

)

func worker(id int, jobs <-chan int, quit <-chan struct{}) {

for {

select {

case job := <-jobs:

fmt.Printf("Worker %d procesando job %d\n", id, job)

time.Sleep(500 * time.Millisecond)

case <-quit:

fmt.Printf("Worker %d: recibida señal de shutdown\n", id)

return

}

}

}

func main() {

jobs := make(chan int, 100)

quit := make(chan struct{})

// Iniciar workers

for i := 1; i <= 3; i++ {

go worker(i, jobs, quit)

}

// Escuchar señales del SO (Ctrl+C)

signals := make(chan os.Signal, 1)

signal.Notify(signals, syscall.SIGINT, syscall.SIGTERM)

// Enviar algunos jobs

go func() {

for i := 1; i <= 10; i++ {

jobs <- i

}

}()

// Esperar señal de terminación

<-signals

fmt.Println("\nRecibida señal de interrupción, iniciando shutdown...")

// Notificar a todos los workers

close(quit)

time.Sleep(time.Second) // Dar tiempo a los workers

fmt.Println("Shutdown completado")

}Prioridad en Select

select no tiene prioridad inherente, pero puedes simularla:

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

high := make(chan int, 10)

low := make(chan int, 10)

// Llenar ambos

for i := 0; i < 5; i++ {

high <- i

low <- i + 100

}

// Prioridad: high sobre low

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

select {

case v := <-high:

fmt.Println("HIGH:", v)

default:

select {

case v := <-low:

fmt.Println("LOW:", v)

default:

fmt.Println("Nada que procesar")

}

}

}

}📊 Resumen de la Parte 4

| Patrón | Uso |

|---|---|

select básico | Esperar múltiples channels |

select + default | Non-blocking check |

select + time.After | Timeout |

select + ticker.C | Operaciones periódicas |

for + select | Loop infinito de eventos |

nil channel en select | Desactivar un case |

flowchart TD

subgraph Select["Lo que aprendiste"]

A[select básico] --> B[default non-blocking]

B --> C[Timeouts]

C --> D[Tickers/Timers]

D --> E[for+select]

E --> F[Graceful shutdown]

end

F --> G[🎛️ Listo para Context]

style G fill:#8b5cf6,color:#fffAhora que dominas channels y select, es hora de aprender la herramienta más importante para control de flujo concurrente: Context.

🎛️ Parte 5: Context - Control de Flujo Concurrente

¿Qué es Context?

El paquete context es la solución estándar de Go para:

- Cancelación: Detener operaciones cuando ya no son necesarias

- Timeouts/Deadlines: Límites de tiempo en operaciones

- Propagación de valores: Pasar datos request-scoped

Analogía del Director de Orquesta:

Imagina una orquesta:

- El director (context padre) puede parar la música

- Cuando el director para, TODOS los músicos paran

- Cada sección puede tener su propio sub-director

- Si el director principal para, todos los sub-directores paran también

Context funciona igual:

- Un context padre cancelado → todos los hijos cancelados

- La cancelación se propaga hacia abajo en el árbolEl Árbol de Contexts

flowchart TD

BG[context.Background] --> CTX1[ctx con timeout]

CTX1 --> CTX2[ctx con cancel]

CTX1 --> CTX3[ctx con valor]

CTX2 --> CTX4[ctx hijo 1]

CTX2 --> CTX5[ctx hijo 2]

style BG fill:#6b7280,color:#fff

style CTX1 fill:#3b82f6,color:#fff

style CTX2 fill:#ef4444,color:#fff

style CTX3 fill:#10b981,color:#fffCrear Contexts

package main

import (

"context"

"fmt"

"time"

)

func main() {

// 1. Context raíz (nunca se cancela)

ctx := context.Background()

// 2. Context vacío (para cuando no sabes qué context usar)

_ = context.TODO()

// 3. Context con cancelación manual

ctxCancel, cancel := context.WithCancel(ctx)

defer cancel() // SIEMPRE llama cancel para liberar recursos

// 4. Context con timeout (se cancela automáticamente)

ctxTimeout, cancelTimeout := context.WithTimeout(ctx, 5*time.Second)

defer cancelTimeout()

// 5. Context con deadline (tiempo absoluto)

deadline := time.Now().Add(5 * time.Second)

ctxDeadline, cancelDeadline := context.WithDeadline(ctx, deadline)

defer cancelDeadline()

// 6. Context con valor

ctxValue := context.WithValue(ctx, "userID", "12345")

fmt.Println("Contexts creados")

fmt.Println("Valor en ctxValue:", ctxValue.Value("userID"))

// Usar el context...

_ = ctxCancel

_ = ctxTimeout

_ = ctxDeadline

}Regla de Oro: Siempre Llamar Cancel

// ✅ CORRECTO: defer cancel() inmediatamente después de crear

ctx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(parentCtx, 5*time.Second)

defer cancel() // Libera recursos cuando la función termina

// ❌ INCORRECTO: Olvidar cancel = memory leak

ctx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(parentCtx, 5*time.Second)

// cancel nunca se llama = goroutine del timer sigue vivaCancelación Manual

package main

import (

"context"

"fmt"

"time"

)

func operacion(ctx context.Context, id int) {

for {

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

fmt.Printf("Operación %d: cancelada (%v)\n", id, ctx.Err())

return

default:

fmt.Printf("Operación %d: trabajando...\n", id)

time.Sleep(500 * time.Millisecond)

}

}

}

func main() {

ctx, cancel := context.WithCancel(context.Background())

// Iniciar 3 operaciones

for i := 1; i <= 3; i++ {

go operacion(ctx, i)

}

// Esperar 2 segundos y cancelar

time.Sleep(2 * time.Second)

fmt.Println("\n--- Cancelando todas las operaciones ---\n")

cancel()

// Dar tiempo para ver los mensajes de cancelación

time.Sleep(100 * time.Millisecond)

}Salida:

Operación 1: trabajando...

Operación 2: trabajando...

Operación 3: trabajando...

Operación 1: trabajando...

Operación 3: trabajando...

Operación 2: trabajando...

Operación 2: trabajando...

Operación 1: trabajando...

Operación 3: trabajando...

--- Cancelando todas las operaciones ---

Operación 1: cancelada (context canceled)

Operación 3: cancelada (context canceled)

Operación 2: cancelada (context canceled)Timeout Automático

package main

import (

"context"

"fmt"

"time"

)

func fetchData(ctx context.Context) (string, error) {

// Simula una operación que tarda 3 segundos

select {

case <-time.After(3 * time.Second):

return "datos obtenidos", nil

case <-ctx.Done():

return "", ctx.Err()

}

}

func main() {

// Timeout de 2 segundos (la operación tarda 3)

ctx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(context.Background(), 2*time.Second)

defer cancel()

fmt.Println("Iniciando fetch...")

start := time.Now()

data, err := fetchData(ctx)

if err != nil {

fmt.Printf("Error después de %v: %v\n", time.Since(start), err)

return

}

fmt.Println("Datos:", data)

}Salida:

Iniciando fetch...

Error después de 2s: context deadline exceededDeadline vs Timeout

package main

import (

"context"

"fmt"

"time"

)

func main() {

ctx := context.Background()

// Timeout: "en 5 segundos desde ahora"

ctxTimeout, cancel1 := context.WithTimeout(ctx, 5*time.Second)

defer cancel1()

// Deadline: "a las 15:30:00 exactamente"

deadline := time.Date(2026, 1, 13, 15, 30, 0, 0, time.Local)

ctxDeadline, cancel2 := context.WithDeadline(ctx, deadline)

defer cancel2()

// Ambos tienen Deadline() method

if d, ok := ctxTimeout.Deadline(); ok {

fmt.Println("Timeout deadline:", d)

}

if d, ok := ctxDeadline.Deadline(); ok {

fmt.Println("Deadline deadline:", d)

}

}Context con Valores

Los valores en context son útiles para datos request-scoped como IDs de traza, tokens de autenticación, etc.

package main

import (

"context"

"fmt"

)

// Usar tipos propios como keys (evita colisiones)

type contextKey string

const (

userIDKey contextKey = "userID"

requestIDKey contextKey = "requestID"

)

func middleware(ctx context.Context) context.Context {

// Agregar valores al context

ctx = context.WithValue(ctx, userIDKey, "user-123")

ctx = context.WithValue(ctx, requestIDKey, "req-456")

return ctx

}

func handler(ctx context.Context) {

// Extraer valores del context

userID := ctx.Value(userIDKey)

requestID := ctx.Value(requestIDKey)

fmt.Printf("Handler: userID=%v, requestID=%v\n", userID, requestID)

}

func main() {

ctx := context.Background()

ctx = middleware(ctx)

handler(ctx)

}Importante sobre valores en context:

// ✅ CORRECTO: Usar para datos request-scoped

ctx = context.WithValue(ctx, requestIDKey, "req-123")

// ❌ INCORRECTO: Usar para pasar parámetros de función

ctx = context.WithValue(ctx, "dbConnection", db) // Mal: pásalo como parámetro

// ❌ INCORRECTO: Usar tipos primitivos como keys

ctx = context.WithValue(ctx, "userID", "123") // Riesgo de colisiónPatrón: Context como Primer Parámetro

En Go, el context siempre es el primer parámetro de una función:

// ✅ CORRECTO: ctx es el primer parámetro

func FetchUser(ctx context.Context, userID string) (*User, error)

func ProcessOrder(ctx context.Context, order Order) error

func SendEmail(ctx context.Context, to, subject, body string) error

// ❌ INCORRECTO: ctx no es el primero

func FetchUser(userID string, ctx context.Context) (*User, error)

// ❌ INCORRECTO: ctx en un struct

type Request struct {

Ctx context.Context // No hagas esto

Data string

}Ejemplo Práctico: HTTP Handler con Context

package main

import (

"context"

"fmt"

"net/http"

"time"

)

func fetchFromDB(ctx context.Context) (string, error) {

// Simula una query lenta

select {

case <-time.After(2 * time.Second):

return "datos de la DB", nil

case <-ctx.Done():

return "", fmt.Errorf("DB query cancelada: %w", ctx.Err())

}

}

func handler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

// El request ya tiene un context (se cancela si el cliente cierra conexión)

ctx := r.Context()

// Agregar timeout adicional

ctx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(ctx, 3*time.Second)

defer cancel()

data, err := fetchFromDB(ctx)

if err != nil {

http.Error(w, err.Error(), http.StatusGatewayTimeout)

return

}

fmt.Fprintf(w, "Datos: %s", data)

}

func main() {

http.HandleFunc("/", handler)

fmt.Println("Servidor en :8080")

http.ListenAndServe(":8080", nil)

}Context en Cadenas de Llamadas

package main

import (

"context"

"fmt"

"time"

)

func operacionA(ctx context.Context) error {

fmt.Println("A: iniciando")

// Verificar cancelación antes de continuar

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

return ctx.Err()

default:

}

// Llamar a B

if err := operacionB(ctx); err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("A falló: %w", err)

}

fmt.Println("A: completada")

return nil

}

func operacionB(ctx context.Context) error {

fmt.Println("B: iniciando")

// Simular trabajo

select {

case <-time.After(1 * time.Second):

fmt.Println("B: trabajo completado")

case <-ctx.Done():

return ctx.Err()

}

// Llamar a C

if err := operacionC(ctx); err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("B falló: %w", err)

}

fmt.Println("B: completada")

return nil

}

func operacionC(ctx context.Context) error {

fmt.Println("C: iniciando")

// Simular trabajo largo

select {

case <-time.After(5 * time.Second):

fmt.Println("C: trabajo completado")

case <-ctx.Done():

fmt.Println("C: cancelada")

return ctx.Err()

}

fmt.Println("C: completada")

return nil

}

func main() {

// Timeout de 3 segundos (C tarda 5)

ctx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(context.Background(), 3*time.Second)

defer cancel()

err := operacionA(ctx)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println("Error:", err)

}

}Salida:

A: iniciando

B: iniciando

B: trabajo completado

C: iniciando

C: cancelada

Error: A falló: B falló: context deadline exceededContext.Cause (Go 1.20+)

Desde Go 1.20 (estable en Go 1.25), puedes proporcionar una causa personalizada para la cancelación:

package main

import (

"context"

"errors"

"fmt"

)

var ErrShutdown = errors.New("servidor apagándose")

func main() {

ctx, cancel := context.WithCancelCause(context.Background())

// Cancelar con causa personalizada

cancel(ErrShutdown)

// Obtener la causa

fmt.Println("Error:", ctx.Err()) // context canceled

fmt.Println("Causa:", context.Cause(ctx)) // servidor apagándose

}AfterFunc (Go 1.21+)

Desde Go 1.21 (mejorado en Go 1.25), context.AfterFunc ejecuta código cuando un context se cancela:

package main

import (

"context"

"fmt"

"time"

)

func main() {

ctx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(context.Background(), 2*time.Second)

defer cancel()

// Registrar cleanup que se ejecuta al cancelar

stop := context.AfterFunc(ctx, func() {

fmt.Println("Cleanup: liberando recursos...")

})

// Si queremos cancelar el AfterFunc antes

_ = stop // stop() cancelaría el callback

// Esperar a que expire el timeout

<-ctx.Done()

time.Sleep(100 * time.Millisecond) // Dar tiempo al callback

}WithoutCancel (Go 1.21+)

Crea un context que NO se cancela cuando el padre se cancela, pero mantiene los valores:

package main

import (

"context"

"fmt"

"time"

)

func backgroundTask(ctx context.Context) {

// Este context NO se cancela cuando el padre se cancela

ctx = context.WithoutCancel(ctx)

for i := 0; i < 5; i++ {

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

fmt.Println("Cancelado")

return

default:

fmt.Printf("Trabajando... (iteración %d)\n", i)

time.Sleep(500 * time.Millisecond)

}

}

fmt.Println("Tarea completada")

}

func main() {

ctx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(context.Background(), 1*time.Second)

go backgroundTask(ctx)

time.Sleep(500 * time.Millisecond)

cancel() // Cancelamos, pero backgroundTask continúa

time.Sleep(3 * time.Second)

}Nuevas Características de Go 1.23-1.25

Go 1.25 incluye mejoras significativas en concurrencia:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"iter"

"slices"

)

// Go 1.23+: Iteradores con range-over-func

func Fibonacci(n int) iter.Seq[int] {

return func(yield func(int) bool) {

a, b := 0, 1

for i := 0; i < n; i++ {

if !yield(a) {

return

}

a, b = b, a+b

}

}

}

// Go 1.23+: Iteradores sobre channels (iter.Pull)

func ChannelToIterator[T any](ch <-chan T) iter.Seq[T] {

return func(yield func(T) bool) {

for v := range ch {

if !yield(v) {

return

}

}

}

}

func main() {

// Range-over-func con iteradores

fmt.Println("Fibonacci:")

for n := range Fibonacci(10) {

fmt.Print(n, " ")

}

fmt.Println()

// Usar slices.Collect para convertir iterador a slice

fibs := slices.Collect(Fibonacci(10))

fmt.Println("Como slice:", fibs)

}unique Package (Go 1.23+)

Deduplicación eficiente de valores para reducir memoria:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"unique"

)

func main() {

// Handle es un identificador único para valores iguales

h1 := unique.Make("hello")

h2 := unique.Make("hello")

h3 := unique.Make("world")

// Comparten la misma memoria subyacente

fmt.Println("h1 == h2:", h1 == h2) // true

fmt.Println("h1 == h3:", h1 == h3) // false

// Recuperar el valor

fmt.Println("Valor:", h1.Value())

// Útil para string interning en sistemas concurrentes

type User struct {

ID int

Role unique.Handle[string] // Roles compartidos eficientemente

}

admin := unique.Make("admin")

users := []User{

{1, admin},

{2, admin}, // Comparte la misma referencia

{3, unique.Make("user")},

}

for _, u := range users {

fmt.Printf("User %d: %s\n", u.ID, u.Role.Value())

}

}Mejoras en sync (Go 1.24-1.25)

package main

import (

"fmt"

"sync"

"sync/atomic"

)

func main() {

// Go 1.19+: Tipos atómicos genéricos (ahora estándar)

var counter atomic.Int64

counter.Add(10)

fmt.Println("Counter:", counter.Load())

// atomic.Pointer[T] para punteros atómicos type-safe

type Config struct {

MaxConn int

Timeout int

}

var currentConfig atomic.Pointer[Config]

currentConfig.Store(&Config{MaxConn: 100, Timeout: 30})

// Lectura atómica sin locks

cfg := currentConfig.Load()

fmt.Printf("Config: MaxConn=%d\n", cfg.MaxConn)

// CompareAndSwap para actualizaciones condicionales

oldCfg := cfg

newCfg := &Config{MaxConn: 200, Timeout: 60}

swapped := currentConfig.CompareAndSwap(oldCfg, newCfg)

fmt.Println("Config actualizada:", swapped)

// sync.OnceValue y sync.OnceValues (Go 1.21+)

getValue := sync.OnceValue(func() int {

fmt.Println("Calculando valor...")

return 42

})

// Solo calcula una vez, múltiples llamadas

fmt.Println(getValue())

fmt.Println(getValue())

fmt.Println(getValue())

}Structured Concurrency Pattern (Go 1.25 idiomático)

Go 1.25 promueve un patrón más estructurado para concurrencia:

package main

import (

"context"

"errors"

"fmt"

"time"

"golang.org/x/sync/errgroup"

)

// Scope define un ámbito de concurrencia estructurada

type Scope struct {

g *errgroup.Group

ctx context.Context

}

func NewScope(ctx context.Context) (*Scope, context.Context) {

g, ctx := errgroup.WithContext(ctx)

return &Scope{g: g, ctx: ctx}, ctx

}

func (s *Scope) Go(fn func(context.Context) error) {

s.g.Go(func() error {

return fn(s.ctx)

})

}

func (s *Scope) Wait() error {

return s.g.Wait()

}

// Ejemplo de uso

func fetchUserData(ctx context.Context, userID int) error {

scope, ctx := NewScope(ctx)

var profile, orders, notifications string

scope.Go(func(ctx context.Context) error {

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

return ctx.Err()

case <-time.After(100 * time.Millisecond):

profile = fmt.Sprintf("Profile-%d", userID)

return nil

}

})

scope.Go(func(ctx context.Context) error {

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

return ctx.Err()

case <-time.After(150 * time.Millisecond):

orders = fmt.Sprintf("Orders-%d", userID)

return nil

}

})

scope.Go(func(ctx context.Context) error {

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

return ctx.Err()

case <-time.After(80 * time.Millisecond):

notifications = fmt.Sprintf("Notifications-%d", userID)

return nil

}

})

if err := scope.Wait(); err != nil {

return err

}

fmt.Printf("User %d: %s, %s, %s\n", userID, profile, orders, notifications)

return nil

}

func main() {

ctx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(context.Background(), 5*time.Second)

defer cancel()

if err := fetchUserData(ctx, 123); err != nil {

fmt.Println("Error:", err)

}

}📊 Resumen de la Parte 5

| Función | Uso |

|---|---|

context.Background() | Context raíz para main/init |

context.TODO() | Placeholder temporal |

context.WithCancel | Cancelación manual |

context.WithTimeout | Timeout relativo |

context.WithDeadline | Deadline absoluto |

context.WithValue | Datos request-scoped |

context.WithCancelCause | Cancelación con causa |

context.WithoutCancel (1.21) | Context que no hereda cancel |

context.AfterFunc (1.21) | Callback al cancelar |

Novedades Go 1.23-1.25:

| Feature | Descripción |

|---|---|

iter.Seq | Iteradores con range-over-func |

unique.Handle | String interning eficiente |

sync.OnceValue | Inicialización lazy type-safe |

atomic.Pointer[T] | Punteros atómicos genéricos |

| Structured concurrency | Patrón errgroup mejorado |

Reglas de uso:

- ✅ Context es siempre el primer parámetro

- ✅ Siempre llamar

cancel()con defer - ✅ Verificar

ctx.Done()en loops largos - ❌ No guardar context en structs

- ❌ No pasar

nilcomo context (usacontext.TODO())

flowchart TD

subgraph Context["Lo que aprendiste"]

A[Background/TODO] --> B[WithCancel]

B --> C[WithTimeout]

C --> D[WithDeadline]

D --> E[WithValue]

E --> F[Propagación]

end

F --> G[🔧 Listo para Patrones]

style G fill:#ec4899,color:#fffCon goroutines, channels, select y context dominados, es hora de aprender patrones de concurrencia profesionales.

🔧 Parte 6: Patrones de Concurrencia

Los patrones de concurrencia son soluciones probadas a problemas comunes. Dominarlos te convierte en un desarrollador Go profesional.

Patrón 1: Worker Pool

Un worker pool es un grupo fijo de goroutines que procesan trabajos de una cola. Controla el paralelismo y evita crear demasiadas goroutines.

flowchart LR

Jobs[Jobs Queue] --> W1[Worker 1]

Jobs --> W2[Worker 2]

Jobs --> W3[Worker 3]

W1 --> Results[Results]

W2 --> Results

W3 --> Results

style Jobs fill:#3b82f6,color:#fff

style Results fill:#10b981,color:#fffpackage main

import (

"context"

"fmt"

"sync"

"time"

)

type Job struct {

ID int

Data string

}

type Result struct {

JobID int

Output string

}

func worker(ctx context.Context, id int, jobs <-chan Job, results chan<- Result, wg *sync.WaitGroup) {

defer wg.Done()

for {

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

fmt.Printf("Worker %d: shutdown\n", id)

return

case job, ok := <-jobs:

if !ok {

fmt.Printf("Worker %d: no más jobs\n", id)

return

}

// Procesar el job

fmt.Printf("Worker %d: procesando job %d\n", id, job.ID)

time.Sleep(500 * time.Millisecond) // Simula trabajo

results <- Result{

JobID: job.ID,

Output: fmt.Sprintf("procesado: %s", job.Data),

}

}

}

}

func main() {

ctx, cancel := context.WithCancel(context.Background())

defer cancel()

const numWorkers = 3

const numJobs = 10

jobs := make(chan Job, numJobs)

results := make(chan Result, numJobs)

// Iniciar workers

var wg sync.WaitGroup

for i := 1; i <= numWorkers; i++ {

wg.Add(1)

go worker(ctx, i, jobs, results, &wg)

}

// Enviar jobs

for i := 1; i <= numJobs; i++ {

jobs <- Job{ID: i, Data: fmt.Sprintf("dato-%d", i)}

}

close(jobs) // Señala que no hay más jobs

// Esperar workers y cerrar results

go func() {

wg.Wait()

close(results)

}()

// Recolectar resultados

for result := range results {

fmt.Printf("Resultado: Job %d -> %s\n", result.JobID, result.Output)

}

}Patrón 2: Fan-Out / Fan-In

Fan-Out: Distribuir trabajo a múltiples goroutines. Fan-In: Combinar resultados de múltiples goroutines en un solo channel.

flowchart LR

subgraph FanOut["Fan-Out"]

Input[Input] --> G1[Goroutine 1]

Input --> G2[Goroutine 2]

Input --> G3[Goroutine 3]

end

subgraph FanIn["Fan-In"]

G1 --> Merge[Merge]

G2 --> Merge

G3 --> Merge

Merge --> Output[Output]

endpackage main

import (

"fmt"

"sync"

"time"

)

// Genera números

func generador(nums ...int) <-chan int {

out := make(chan int)

go func() {

for _, n := range nums {

out <- n

}

close(out)

}()

return out

}

// Fan-Out: Crea múltiples procesadores

func procesador(in <-chan int) <-chan int {

out := make(chan int)

go func() {

for n := range in {

time.Sleep(100 * time.Millisecond) // Simula trabajo

out <- n * n

}

close(out)

}()

return out

}

// Fan-In: Combina múltiples channels en uno

func fanIn(channels ...<-chan int) <-chan int {

out := make(chan int)

var wg sync.WaitGroup

// Goroutine por cada channel de entrada

for _, ch := range channels {

wg.Add(1)

go func(c <-chan int) {

defer wg.Done()

for n := range c {

out <- n

}

}(ch)

}

// Cerrar out cuando todos terminen

go func() {

wg.Wait()

close(out)

}()

return out

}

func main() {

start := time.Now()

// Generador

nums := generador(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10)

// Fan-Out: 3 procesadores leyendo del mismo channel

p1 := procesador(nums)

p2 := procesador(nums)

p3 := procesador(nums)

// Fan-In: Combinar resultados

resultados := fanIn(p1, p2, p3)

// Consumir resultados

for r := range resultados {

fmt.Println(r)

}

fmt.Printf("Tiempo total: %v\n", time.Since(start))

}Patrón 3: Pipeline

Un pipeline es una serie de etapas conectadas por channels, donde cada etapa procesa y pasa datos a la siguiente.

package main

import (

"context"

"fmt"

)

// Etapa 1: Generar números

func generate(ctx context.Context, nums ...int) <-chan int {

out := make(chan int)

go func() {

defer close(out)

for _, n := range nums {

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

return

case out <- n:

}

}

}()

return out

}

// Etapa 2: Elevar al cuadrado

func square(ctx context.Context, in <-chan int) <-chan int {

out := make(chan int)

go func() {

defer close(out)

for n := range in {

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

return

case out <- n * n:

}

}

}()

return out

}

// Etapa 3: Filtrar pares

func filterEven(ctx context.Context, in <-chan int) <-chan int {

out := make(chan int)

go func() {

defer close(out)

for n := range in {

if n%2 == 0 {

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

return

case out <- n:

}

}

}

}()

return out

}

func main() {

ctx, cancel := context.WithCancel(context.Background())

defer cancel()

// Pipeline: generate -> square -> filterEven

// 1,2,3,4,5 -> 1,4,9,16,25 -> 4,16

for n := range filterEven(ctx, square(ctx, generate(ctx, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5))) {

fmt.Println(n)

}

}Patrón 4: Semáforo (Limitar Concurrencia)

Cuando necesitas limitar cuántas goroutines ejecutan simultáneamente:

package main

import (

"context"

"fmt"

"time"

)

type Semaphore chan struct{}

func NewSemaphore(size int) Semaphore {

return make(chan struct{}, size)

}

func (s Semaphore) Acquire() {

s <- struct{}{}

}

func (s Semaphore) Release() {

<-s

}

func proceso(id int) {

fmt.Printf("Proceso %d: iniciando\n", id)

time.Sleep(time.Second)

fmt.Printf("Proceso %d: terminando\n", id)

}

func main() {

ctx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(context.Background(), 10*time.Second)

defer cancel()

// Máximo 3 procesos simultáneos

sem := NewSemaphore(3)

for i := 1; i <= 10; i++ {

i := i

sem.Acquire() // Espera si ya hay 3 ejecutando

go func() {

defer sem.Release()

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

return

default:

proceso(i)

}

}()

}

// Esperar a que todos terminen adquiriendo todos los slots

for i := 0; i < cap(sem); i++ {

sem.Acquire()

}

fmt.Println("Todos los procesos completados")

}Patrón 5: Or-Done Channel

Permite leer de un channel respetando la cancelación del context:

package main

import (

"context"

"fmt"

"time"

)

// orDone envuelve un channel para respetar cancelación

func orDone(ctx context.Context, c <-chan int) <-chan int {

out := make(chan int)

go func() {

defer close(out)

for {

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

return

case v, ok := <-c:

if !ok {

return

}

select {

case out <- v:

case <-ctx.Done():

return

}

}

}

}()

return out

}

func main() {

ctx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(context.Background(), 2*time.Second)

defer cancel()

// Generador lento

nums := make(chan int)

go func() {

defer close(nums)

for i := 1; i <= 100; i++ {

time.Sleep(500 * time.Millisecond)

nums <- i

}

}()

// Usar orDone para respetar timeout

for n := range orDone(ctx, nums) {

fmt.Println(n)

}

fmt.Println("Terminado (timeout o completado)")

}Patrón 6: Errgroup (Manejo de Errores en Grupos)

El paquete golang.org/x/sync/errgroup es la forma profesional de manejar errores en grupos de goroutines:

package main

import (

"context"

"errors"

"fmt"

"time"

"golang.org/x/sync/errgroup"

)

func fetchUser(ctx context.Context, id int) (string, error) {

select {

case <-time.After(100 * time.Millisecond):

return fmt.Sprintf("User-%d", id), nil

case <-ctx.Done():

return "", ctx.Err()

}

}

func fetchOrder(ctx context.Context, id int) (string, error) {

select {

case <-time.After(200 * time.Millisecond):

if id == 3 {

return "", errors.New("order not found")

}

return fmt.Sprintf("Order-%d", id), nil

case <-ctx.Done():

return "", ctx.Err()

}

}

func main() {

ctx := context.Background()

g, ctx := errgroup.WithContext(ctx)

var user, order string

g.Go(func() error {

var err error

user, err = fetchUser(ctx, 1)

return err

})

g.Go(func() error {

var err error

order, err = fetchOrder(ctx, 3) // Este fallará

return err

})

// Wait retorna el primer error (si hay alguno)

if err := g.Wait(); err != nil {

fmt.Println("Error:", err)

return

}

fmt.Printf("User: %s, Order: %s\n", user, order)

}Patrón 7: Singleflight (Deduplicación)

Evita trabajo duplicado cuando múltiples goroutines piden lo mismo:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"sync"

"time"

"golang.org/x/sync/singleflight"

)

var group singleflight.Group

func fetchData(key string) (string, error) {

fmt.Printf("Fetching %s (heavy operation)\n", key)

time.Sleep(time.Second)

return fmt.Sprintf("data-for-%s", key), nil

}

func getData(key string) (string, error) {

// Singleflight asegura que solo una goroutine hace el fetch

v, err, shared := group.Do(key, func() (interface{}, error) {

return fetchData(key)

})

fmt.Printf("Key: %s, Shared: %t\n", key, shared)

return v.(string), err

}

func main() {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

// 10 goroutines pidiendo el mismo key

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

wg.Add(1)

go func(id int) {

defer wg.Done()

data, _ := getData("important-key")

fmt.Printf("Goroutine %d got: %s\n", id, data)

}(i)

}

wg.Wait()

}Salida:

Fetching important-key (heavy operation)

Key: important-key, Shared: false

Key: important-key, Shared: true

Key: important-key, Shared: true

... (todas comparten el mismo resultado)Patrón 8: Rate Limiter

Limitar la tasa de operaciones:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func main() {

// Rate limiter: 5 requests por segundo

limiter := time.NewTicker(200 * time.Millisecond)

defer limiter.Stop()

requests := []int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10}

for _, req := range requests {

<-limiter.C // Esperar el tick

go func(r int) {

fmt.Printf("Request %d at %v\n", r, time.Now().Format("15:04:05.000"))

}(req)

}

time.Sleep(time.Second)

}Rate Limiter con Burst (usando buffered channel):

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func main() {

// Permite burst de 3, luego 1 por cada 200ms

burstyLimiter := make(chan time.Time, 3)

// Llenar el burst inicial

for i := 0; i < 3; i++ {

burstyLimiter <- time.Now()

}

// Reponer 1 cada 200ms

go func() {

for t := range time.Tick(200 * time.Millisecond) {

burstyLimiter <- t

}

}()

requests := []int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8}

for _, req := range requests {

<-burstyLimiter

fmt.Printf("Request %d at %v\n", req, time.Now().Format("15:04:05.000"))

}

}📊 Resumen de la Parte 6

| Patrón | Uso |

|---|---|

| Worker Pool | Control de paralelismo |

| Fan-Out/Fan-In | Distribuir y combinar trabajo |

| Pipeline | Procesamiento en etapas |

| Semáforo | Limitar concurrencia |

| Or-Done | Channel + cancelación |

| Errgroup | Errores en grupos |

| Singleflight | Deduplicación |

| Rate Limiter | Control de tasa |

flowchart TD

subgraph Patrones["Lo que aprendiste"]

A[Worker Pool] --> B[Fan-Out/Fan-In]

B --> C[Pipeline]

C --> D[Semáforo]

D --> E[Errgroup]

E --> F[Singleflight]

F --> G[Rate Limiter]

end

G --> H[⚠️ Race Conditions]

style H fill:#ef4444,color:#fffAhora que conoces los patrones, es crucial entender el enemigo: Race Conditions.

⚠️ Parte 7: Race Conditions - El Enemigo Silencioso

¿Qué es una Race Condition?

Una race condition ocurre cuando dos o más goroutines acceden a la misma variable concurrentemente, y al menos una la modifica. El resultado depende del orden de ejecución, que es impredecible.

Analogía de la Cuenta Bancaria:

Imagina una cuenta bancaria con $100:

Goroutine A: Leer saldo ($100) → Sumar $50 → Escribir ($150)

Goroutine B: Leer saldo ($100) → Restar $30 → Escribir ($70)

Si ambas leen ANTES de que la otra escriba:

- Ambas ven $100

- A escribe $150

- B escribe $70

Resultado final: $70 (¡perdimos $50!)

Resultado esperado: $120Race Condition en Go

package main

import (

"fmt"

"sync"

)

func main() {

counter := 0

var wg sync.WaitGroup

// 1000 goroutines incrementando el mismo counter

for i := 0; i < 1000; i++ {

wg.Add(1)

go func() {

defer wg.Done()

counter++ // ¡RACE CONDITION!

}()

}

wg.Wait()

fmt.Println("Counter:", counter)

// Resultado: Probablemente < 1000 (debería ser 1000)

}¿Por qué counter++ no es atómico?

counter++ se traduce a:

1. Leer counter de memoria

2. Incrementar el valor

3. Escribir counter a memoria

Si G1 y G2 hacen esto simultáneamente:

G1: Lee 5 G2: Lee 5

G1: +1 = 6 G2: +1 = 6

G1: Escribe 6 G2: Escribe 6

Resultado: 6 (debería ser 7)El Race Detector de Go

Go tiene un detector de races incorporado. Es una de las mejores herramientas para encontrar bugs de concurrencia:

# Ejecutar con detector de races

go run -race main.go

# Testear con detector de races

go test -race ./...

# Compilar con detector de races

go build -race -o myappEjemplo de salida del race detector:

==================

WARNING: DATA RACE

Write at 0x00c0000140a8 by goroutine 7:

main.main.func1()

/path/main.go:14 +0x4a

Previous write at 0x00c0000140a8 by goroutine 6:

main.main.func1()

/path/main.go:14 +0x4a

Goroutine 7 (running) created at:

main.main()

/path/main.go:12 +0x7e

Goroutine 6 (finished) created at:

main.main()

/path/main.go:12 +0x7e

==================⚠️ IMPORTANTE:

- Usa

-raceen desarrollo y testing, no en producción - El race detector añade ~2-10x overhead

- Solo detecta races que ocurren durante la ejecución

Solución 1: sync.Mutex

Un Mutex (mutual exclusion) asegura que solo una goroutine acceda a la sección crítica a la vez:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"sync"

)

func main() {

counter := 0

var mu sync.Mutex

var wg sync.WaitGroup

for i := 0; i < 1000; i++ {

wg.Add(1)

go func() {

defer wg.Done()

mu.Lock() // Adquirir el lock

counter++ // Sección crítica

mu.Unlock() // Liberar el lock

}()

}

wg.Wait()

fmt.Println("Counter:", counter) // Siempre 1000

}Patrón recomendado con defer:

func incrementar(mu *sync.Mutex, counter *int) {

mu.Lock()

defer mu.Unlock() // SIEMPRE libera, incluso con panic

*counter++