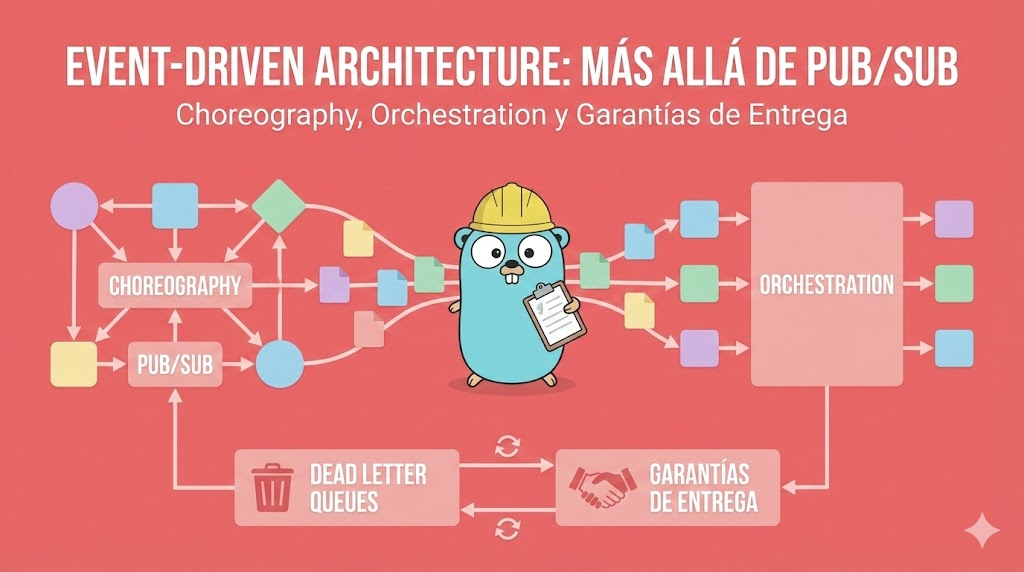

Event-Driven Architecture: Más Allá de Pub/Sub - Choreography, Orchestration y Garantías de Entrega

Una guía profunda sobre arquitectura orientada a eventos en Go: diferencia entre choreography y orchestration, cómo manejar dead letter queues, retries inteligentes, garantías de entrega en REST, y patrones verificables en producción.

Existe una mentira común que escucho en reuniones de arquitectura:

“Vamos a hacer event-driven architecture. Ponemos un Kafka/RabbitMQ, publicamos eventos, nos suscribimos a eventos, y listo: somos event-driven.”

No. Eso es solo agregar un message broker a tu sistema. Event-driven architecture es algo fundamentalmente diferente: es una forma de pensar sobre cómo los componentes de tu sistema interactúan, se comunican, y logran consistencia.

La diferencia entre tener un message broker y tener arquitectura event-driven real es la diferencia entre tener un martillo y ser carpintero.

He visto equipos que agregaron Kafka “para ser modernos” y terminaron con un sistema más complejo, más lento, más difícil de debuggear, y sin ningún beneficio real. He visto otros que entendieron realmente event-driven architecture, implementaron correctamente, y transformaron completamente cómo sus sistemas funcionan.

La diferencia está en tres decisiones arquitectónicas fundamentales que casi nadie enseña: Choreography vs Orchestration, cómo manejar fallos (Dead Letter Queues), y cómo garantizar que los eventos se procesen correctamente en REST.

Este artículo es una inmersión profunda en estos tres pilares. No es introducción. Es desmenuzo de decisiones reales que harás, código que verás en producción, y patrones que transformarán cómo diseñas sistemas.

Parte 1: Fundamentos de Event-Driven Architecture

1.1 ¿Qué es Realmente Event-Driven?

Event-driven architecture es un patrón donde:

- El cambio de estado genera eventos

- Otros componentes se suscriben a esos eventos

- Los componentes actúan basados en los eventos que reciben

- Los componentes NO conocen directamente uno al otro

La clave es #4: desacoplamiento.

Comparemos dos formas de hacer lo mismo:

Forma Tradicional (Acoplada):

type OrderService struct {

paymentService *PaymentService

shippingService *ShippingService

emailService *EmailService

inventoryService *InventoryService

}

func (s *OrderService) CreateOrder(order *Order) error {

// 1. Procesar pago

if err := s.paymentService.Charge(order); err != nil {

return err

}

// 2. Actualizar inventario

if err := s.inventoryService.Update(order); err != nil {

return err

}

// 3. Iniciar envío

if err := s.shippingService.Schedule(order); err != nil {

return err

}

// 4. Enviar email

if err := s.emailService.Send(order); err != nil {

return err

}

return nil

}Problemas:

- ❌ OrderService conoce todos los servicios

- ❌ Si EmailService falla, toda la operación falla

- ❌ Si necesitas agregar NotificationService, modifica OrderService

- ❌ Testing requiere 4 mocks

- ❌ Escalabilidad limitada (esperas a todo secuencialmente)

Forma Event-Driven:

type OrderService struct {

orderRepo OrderRepository

eventBus EventBus

}

func (s *OrderService) CreateOrder(order *Order) error {

// 1. Persistir orden

if err := s.orderRepo.Save(order); err != nil {

return err

}

// 2. Publicar evento

event := OrderCreatedEvent{

OrderID: order.ID,

Total: order.Total,

Items: order.Items,

}

if err := s.eventBus.Publish(event); err != nil {

return err

}

return nil

}Otros servicios se suscriben:

// PaymentService

func (s *PaymentService) OnOrderCreated(event OrderCreatedEvent) {

// Procesar pago

}

// InventoryService

func (s *InventoryService) OnOrderCreated(event OrderCreatedEvent) {

// Actualizar stock

}

// ShippingService

func (s *ShippingService) OnOrderCreated(event OrderCreatedEvent) {

// Iniciar envío

}

// EmailService

func (s *EmailService) OnOrderCreated(event OrderCreatedEvent) {

// Enviar confirmación

}Ventajas:

- ✅ OrderService NO conoce otros servicios

- ✅ Si EmailService falla, no afecta a OrderService

- ✅ Agregar NotificationService = agregar subscriber

- ✅ Testing aislado

- ✅ Procesamiento paralelo (EventBus distribuye en paralelo)

Pero aquí viene lo importante: la pregunta de cómo orquestar estos eventos no es trivial.

Parte 2: Choreography vs Orchestration

2.1 Choreography: “Cada Quien Sabe su Pasos”

En choreography, los eventos mismos coordinan el flujo. Cada servicio sabe qué hacer cuando recibe un evento, y publica nuevos eventos como resultado.

1. OrderService publica: OrderCreated

↓

2. PaymentService recibe: OrderCreated

→ Procesa pago

→ Publica: PaymentProcessed (o PaymentFailed)

↓

3. InventoryService recibe: OrderCreated

→ Actualiza stock

→ Publica: StockUpdated

↓

4. ShippingService recibe: OrderCreated

→ Programa envío

→ Publica: ShipmentScheduledEl flujo es implícito: emergente de los eventos.

Implementación en Go:

// PaymentService

type PaymentService struct {

eventBus EventBus

paymentRepo PaymentRepository

}

func (s *PaymentService) HandleOrderCreated(event OrderCreatedEvent) {

payment := &Payment{

OrderID: event.OrderID,

Amount: event.Total,

Status: "pending",

}

// Procesar pago (con PaymentGateway)

if err := s.gateway.Charge(event.Total); err != nil {

// Publicar fallo

s.eventBus.Publish(PaymentFailedEvent{

OrderID: event.OrderID,

Reason: err.Error(),

})

return

}

// Persistir

s.paymentRepo.Save(payment)

// Publicar éxito (esto dispara otros servicios)

s.eventBus.Publish(PaymentProcessedEvent{

OrderID: event.OrderID,

TransactionID: payment.TransactionID,

})

}

// InventoryService escucha a OrderCreated

type InventoryService struct {

eventBus EventBus

inventoryRepo InventoryRepository

}

func (s *InventoryService) HandleOrderCreated(event OrderCreatedEvent) {

// Actualizar stock

for _, item := range event.Items {

s.inventoryRepo.Decrement(item.ProductID, item.Quantity)

}

// Publicar (otros servicios podrían estar esperando)

s.eventBus.Publish(StockUpdatedEvent{

OrderID: event.OrderID,

})

}Ventajas de Choreography:

✅ Simple de entender: El flujo emerge de eventos naturales

✅ Desacoplamiento: Cada servicio es independiente

✅ Escalabilidad: Fácil agregar nuevos subscribers

✅ Performance: Paralelo por naturaleza

Desventajas de Choreography:

❌ Difícil de rastrear: ¿Qué paso después de OrderCreated? Solo si lees todos los servicios

❌ Difícil de debuggear: “¿Por qué mi orden no se procesó?” Necesitas seguir la cadena de eventos

❌ Dependencias ocultas: El servicio A depende del servicio B, pero la dependencia está implícita en el evento

❌ Transacciones distribuidas complejas: Si necesitas rollback, ¿qué haces?

2.2 Orchestration: “El Maestro Dirige”

En orchestration, existe un orquestador central que conoce el flujo y lo coordina explícitamente.

OrderOrchestrator conoce el flujo:

1. Recibe: CreateOrderRequest

2. Llama: OrderService.Create() → OrderCreated

3. Espera → Llama: PaymentService.Process() → PaymentProcessed

4. Espera → Llama: InventoryService.Update() → StockUpdated

5. Espera → Llama: ShippingService.Schedule() → ShipmentScheduled

6. Retorna: OrderCreatedEventEl flujo es explícito: definido en el orquestador.

Implementación en Go:

// El Orquestador conoce el flujo

type OrderOrchestrator struct {

orderService OrderService

paymentService PaymentService

inventoryService InventoryService

shippingService ShippingService

}

func (o *OrderOrchestrator) Execute(order *Order) error {

// 1. Crear orden

createdOrder, err := o.orderService.Create(order)

if err != nil {

return err

}

// 2. Procesar pago

paymentResult, err := o.paymentService.Process(createdOrder)

if err != nil {

// Compensar: revertir orden

o.orderService.Cancel(createdOrder.ID)

return err

}

// 3. Actualizar inventario

if err := o.inventoryService.Update(createdOrder); err != nil {

// Compensar: revertir pago

o.paymentService.Refund(paymentResult.TransactionID)

o.orderService.Cancel(createdOrder.ID)

return err

}

// 4. Programar envío

if err := o.shippingService.Schedule(createdOrder); err != nil {

// Compensar: revertir inventario

o.inventoryService.Restore(createdOrder)

o.paymentService.Refund(paymentResult.TransactionID)

o.orderService.Cancel(createdOrder.ID)

return err

}

// Si llegó aquí, todo éxito

return nil

}Esto implementa el Saga Pattern con transacciones distribuidas.

Ventajas de Orchestration:

✅ Claro: El flujo está explícitamente definido

✅ Fácil de entender: Un archivo define todo

✅ Fácil de debuggear: Sabes exactamente qué pasos se ejecutaron

✅ Transacciones distribuidas: Puedes implementar compensating transactions

✅ Monitoreo: Rastrear progreso es trivial

Desventajas de Orchestration:

❌ Acoplamiento: El orquestador conoce todos los servicios

❌ Single point of failure: Si el orquestador falla, todo falla

❌ Escalabilidad: Agregar nuevo paso requiere modificar orquestador

❌ Complejidad: Lógica de compensación puede ser complicada

2.3 ¿Cuál Elegir? (La Verdadera Decisión)

Elige Choreography si:

- Los pasos son realmente independientes

- El flujo es simple y pocos pasos

- Los servicios pueden fallar sin afectar el estado global

- Cada paso es idempotente

Elige Orchestration si:

- Hay orden específico obligatorio

- Necesitas transacciones distribuidas (compensating transactions)

- El flujo es complejo (muchos pasos, muchas condiciones)

- Necesitas visibilidad y auditoría del flujo

Mi recomendación: Hybrid. Usa orchestration para el flujo principal, choreography para eventos secundarios.

// Orquestador maneja lo crítico

type OrderOrchestrator struct {

orderService OrderService

paymentService PaymentService

eventBus EventBus // Para eventos secundarios

}

func (o *OrderOrchestrator) Execute(order *Order) error {

createdOrder, _ := o.orderService.Create(order)

paymentResult, err := o.paymentService.Process(createdOrder)

if err != nil {

// Compensar

o.orderService.Cancel(createdOrder.ID)

return err

}

// Lo demás, que otros servicios lo manejen por eventos

o.eventBus.Publish(OrderReadyEvent{OrderID: createdOrder.ID})

// InventoryService, ShippingService, EmailService se suscriben

return nil

}Parte 3: Dead Letter Queues y Retries

3.1 El Problema: Cuando Las Cosas Fallan

Imagina este escenario:

1. OrderService publica: OrderCreated

2. EmailService recibe e intenta enviar email

3. EmailService falla: Error de conexión a SMTP

4. El evento se pierde. La orden se crea pero el usuario nunca recibe confirmación.¿Qué pasó? Los eventos se perdieron porque no había mecanismo de manejo de fallos.

Este es el problema que resuelven Dead Letter Queues (DLQ) y retries.

3.2 Retries: Lo Primero

Cuando un procesador de eventos falla, deberías reintentar automáticamente:

type EventProcessor struct {

eventBus EventBus

maxRetries int = 3

retryDelay time.Duration = 1 * time.Second

}

func (p *EventProcessor) ProcessEvent(event Event) error {

var lastErr error

// Reintentar con backoff exponencial

for attempt := 0; attempt < p.maxRetries; attempt++ {

err := p.handleEvent(event)

if err == nil {

return nil // Éxito

}

lastErr = err

// Backoff exponencial: 1s, 2s, 4s

waitTime := time.Duration(math.Pow(2, float64(attempt))) * p.retryDelay

time.Sleep(waitTime)

}

// Si llegó aquí, falló después de todos los retries

return lastErr

}

func (p *EventProcessor) handleEvent(event Event) error {

// Tu lógica aquí

// Puede fallar por razones transitorias (conexión temporal, timeout, etc)

}Importante: NO todos los errores merecen retry. Algunos son permanentes:

func (p *EventProcessor) shouldRetry(err error) bool {

switch err {

case ErrInvalidEmail: // Permanente: datos malos

return false

case ErrSMTPConnection: // Temporal: falla de conexión

return true

case ErrDatabaseTimeout: // Temporal

return true

case context.DeadlineExceeded: // Temporal

return true

default:

return true // Por defecto, reintentar

}

}

func (p *EventProcessor) ProcessEvent(event Event) error {

var lastErr error

for attempt := 0; attempt < p.maxRetries; attempt++ {

err := p.handleEvent(event)

if err == nil {

return nil

}

if !p.shouldRetry(err) {

return err // Permanente, no reintentar

}

lastErr = err

time.Sleep(p.backoffDuration(attempt))

}

return lastErr

}3.3 Dead Letter Queues: Lo Último

Cuando todos los retries fallan, el evento va a la Dead Letter Queue (DLQ).

La DLQ es un queue especial donde viven eventos que no pudieron procesarse. Son para inspección manual.

type EventBroker struct {

mainQueue chan Event

dlq chan DeadLetterEvent

maxRetries int

}

type DeadLetterEvent struct {

OriginalEvent Event

Error string

Timestamp time.Time

Attempts int

}

func (b *EventBroker) ProcessEvent(event Event) {

attempt := 0

for {

err := b.processWithTimeout(event)

if err == nil {

return // Éxito

}

attempt++

if attempt >= b.maxRetries {

// Enviar a DLQ

b.dlq <- DeadLetterEvent{

OriginalEvent: event,

Error: err.Error(),

Timestamp: time.Now(),

Attempts: attempt,

}

return

}

// Retry con backoff

time.Sleep(time.Duration(math.Pow(2, float64(attempt-1))) * time.Second)

}

}

func (b *EventBroker) processWithTimeout(event Event) error {

ctx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(context.Background(), 5*time.Second)

defer cancel()

// Tu procesamiento aquí

return b.handler.Handle(ctx, event)

}¿Qué hacer con eventos en DLQ?

- Alertar: “Hay 5 eventos sin procesar, invesiga”

- Loguear detalladamente: Para debugging

- Dashboard: Visualizar eventos fallidos

- Retry manual: “Procesá este evento de nuevo”

type DLQMonitor struct {

dlq chan DeadLetterEvent

alertService AlertService

logger Logger

}

func (m *DLQMonitor) Monitor(ctx context.Context) {

failedCount := 0

for {

select {

case dlEvent := <-m.dlq:

failedCount++

m.logger.Error("Event in DLQ",

"event_id", dlEvent.OriginalEvent.ID,

"error", dlEvent.Error,

"attempts", dlEvent.Attempts,

)

if failedCount > 10 {

m.alertService.Alert("DLQ tiene más de 10 eventos")

failedCount = 0

}

case <-ctx.Done():

return

}

}

}3.4 Idempotencia: El Verdadero Secreto

De nada sirven retries si no son idempotentes. Un evento procesado dos veces debe tener el mismo resultado que procesado una vez.

// ❌ NO IDEMPOTENTE

func (s *AccountService) HandleMoneyAdded(event MoneyAddedEvent) error {

account, _ := s.repo.GetByID(event.AccountID)

account.Balance += event.Amount

s.repo.Save(account) // Si esto se ejecuta dos veces, balance duplica

return nil

}

// ✅ IDEMPOTENTE

func (s *AccountService) HandleMoneyAdded(event MoneyAddedEvent) error {

account, _ := s.repo.GetByID(event.AccountID)

// Verifica si el evento ya fue procesado

processed, _ := s.repo.IsEventProcessed(event.ID)

if processed {

return nil // Ya procesado, no hacer nada

}

account.Balance += event.Amount

s.repo.Save(account)

// Marcar evento como procesado (en la misma transacción)

s.repo.MarkEventProcessed(event.ID)

return nil

}Mejor aún: usar una tabla de “processed events”:

// En BD

CREATE TABLE processed_events (

event_id UUID PRIMARY KEY,

service_name VARCHAR,

processed_at TIMESTAMP

);

func (s *AccountService) HandleMoneyAdded(event MoneyAddedEvent) error {

tx := s.db.BeginTx(ctx, nil)

// Check idempotencia

var exists bool

tx.QueryRow(

"SELECT COUNT(*) FROM processed_events WHERE event_id = $1 AND service_name = $2",

event.ID, "AccountService",

).Scan(&exists)

if exists {

tx.Rollback()

return nil

}

// Procesar

account, _ := s.repo.GetByID(event.AccountID)

account.Balance += event.Amount

s.repo.Save(account)

// Marcar

tx.Exec(

"INSERT INTO processed_events (event_id, service_name, processed_at) VALUES ($1, $2, $3)",

event.ID, "AccountService", time.Now(),

)

tx.Commit()

return nil

}Parte 4: Garantías de Entrega en REST

4.1 El Problema: REST No Es Fiable

HTTP y REST tienen un problema fundamental: no son fiables por naturaleza.

POST /orders

{

"items": [...],

"user_id": "123"

}

Posibles resultados:

1. Éxito: 201 Created

2. Error: 400 Bad Request

3. ??? El servidor procesó pero la respuesta se perdió

4. ??? El servidor no procesó y el cliente nunca lo supoEl problema #3 y #4 son el verdadero reto.

4.2 Idempotency Keys: La Solución

La solución es Idempotency Keys: el cliente genera un identificador único para la operación, y el servidor usa ese identificador para evitar procesamiento duplicado.

// Cliente (por ejemplo, frontend o mobile)

func (c *Client) CreateOrder(order Order) error {

idempotencyKey := uuid.New().String()

req, _ := http.NewRequest("POST", "/orders", body)

req.Header.Set("Idempotency-Key", idempotencyKey)

resp, err := c.httpClient.Do(req)

// Si falla por razones de red, puede reintentar con el mismo key

// El servidor no procesará dos veces

}

// Servidor

func (h *OrderHandler) Create(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

idempotencyKey := r.Header.Get("Idempotency-Key")

if idempotencyKey == "" {

http.Error(w, "Idempotency-Key header required", http.StatusBadRequest)

return

}

// Verificar si ya existe

existingOrder, _ := h.orderRepo.GetByIdempotencyKey(idempotencyKey)

if existingOrder != nil {

// Ya procesado: retornar el mismo resultado

w.Header().Set("X-Idempotency-Replayed", "true")

w.WriteHeader(http.StatusCreated)

json.NewEncoder(w).Encode(existingOrder)

return

}

// Procesar nueva orden (dentro de una transacción)

tx := h.db.BeginTx(r.Context(), nil)

order := &Order{...}

h.orderRepo.Save(tx, order)

// Guardar idempotency key (transacción atómica)

h.repo.SaveIdempotencyKey(tx, idempotencyKey, order.ID)

tx.Commit()

w.WriteHeader(http.StatusCreated)

json.NewEncoder(w).Encode(order)

}Implementación en BD:

CREATE TABLE idempotency_keys (

key UUID PRIMARY KEY,

service VARCHAR NOT NULL,

resource_id VARCHAR NOT NULL,

request_body JSON,

response_body JSON,

status_code INT,

created_at TIMESTAMP,

UNIQUE(service, resource_id)

);

-- Índice para limpieza automática (borrar keys antiguas)

CREATE INDEX idx_created_at ON idempotency_keys(created_at);4.3 Webhook Delivery: El Desafío Real

Si TÚ necesitas entregar eventos a clientes via webhooks (POST a su servidor), tienes que garantizar entrega.

type WebhookDelivery struct {

EventID string

CustomerWebhookURL string

Payload interface{}

Attempts int

NextRetryAt time.Time

}

type WebhookService struct {

db *sql.DB

httpClient *http.Client

maxRetries int

}

func (s *WebhookService) DeliverWebhook(webhook WebhookDelivery) error {

payload, _ := json.Marshal(webhook.Payload)

req, _ := http.NewRequest("POST", webhook.CustomerWebhookURL, bytes.NewReader(payload))

req.Header.Set("X-Event-ID", webhook.EventID) // Permitir idempotencia en cliente

req.Header.Set("X-Delivery-Attempt", fmt.Sprintf("%d", webhook.Attempts))

ctx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(context.Background(), 10*time.Second)

defer cancel()

resp, err := s.httpClient.Do(req.WithContext(ctx))

if err != nil {

// Error de red, reintentar

webhook.Attempts++

if webhook.Attempts < s.maxRetries {

webhook.NextRetryAt = time.Now().Add(

time.Duration(math.Pow(2, float64(webhook.Attempts-1))) * time.Second,

)

s.db.Exec(

"UPDATE webhooks SET attempts = $1, next_retry_at = $2 WHERE event_id = $3",

webhook.Attempts, webhook.NextRetryAt, webhook.EventID,

)

} else {

// Enviar a DLQ

s.db.Exec("UPDATE webhooks SET status = 'failed' WHERE event_id = $1", webhook.EventID)

}

return err

}

defer resp.Body.Close()

if resp.StatusCode >= 200 && resp.StatusCode < 300 {

// Éxito

s.db.Exec("UPDATE webhooks SET status = 'delivered' WHERE event_id = $1", webhook.EventID)

return nil

}

if resp.StatusCode >= 500 {

// Error temporal (servidor cliente caído), reintentar

webhook.Attempts++

if webhook.Attempts < s.maxRetries {

webhook.NextRetryAt = time.Now().Add(

time.Duration(math.Pow(2, float64(webhook.Attempts-1))) * time.Second,

)

s.db.Exec("UPDATE webhooks SET attempts = $1, next_retry_at = $2 WHERE event_id = $3",

webhook.Attempts, webhook.NextRetryAt, webhook.EventID)

}

} else {

// Error permanente (400, 401, 404, etc), no reintentar

s.db.Exec("UPDATE webhooks SET status = 'failed' WHERE event_id = $1", webhook.EventID)

}

return fmt.Errorf("webhook delivery failed with status %d", resp.StatusCode)

}Tabla para webhooks:

CREATE TABLE webhook_deliveries (

id UUID PRIMARY KEY,

event_id UUID NOT NULL,

customer_id UUID NOT NULL,

webhook_url VARCHAR NOT NULL,

payload JSONB NOT NULL,

status VARCHAR DEFAULT 'pending', -- pending, delivered, failed

attempts INT DEFAULT 0,

last_attempt_at TIMESTAMP,

next_retry_at TIMESTAMP,

created_at TIMESTAMP,

FOREIGN KEY (customer_id) REFERENCES customers(id)

);

CREATE INDEX idx_status_retry ON webhook_deliveries(status, next_retry_at)

WHERE status = 'pending';4.4 Garantías Reales: At-Least-Once vs Exactly-Once

At-Least-Once: El evento se procesa al menos una vez, pero podría procesarse múltiples veces. Requiere idempotencia.

Exactly-Once: El evento se procesa exactamente una vez. Es más difícil de lograr y más caro.

Para REST APIs, At-Least-Once + Idempotencia es el patrón estándar:

// Exactamente-una-vez requiere transacción distribuida:

// 1. Reservar recurso (ej: dinero en cuenta)

// 2. Procesar evento

// 3. Confirmar (commit)

// Si algo falla entre 1-3, tenemos estado reservado, no es ideal.

// At-Least-Once + Idempotencia es más pragmático:

// 1. Cliente envía: POST /orders con Idempotency-Key: "abc123"

// 2. Servidor procesa y guarda orden + clave idempotencia

// 3. Cliente recibe: 201 Created

// 4. Si cliente no recibe respuesta, reintenta con mismo Idempotency-Key

// 5. Servidor devuelve misma respuesta (sin procesar de nuevo)

// Resultado: Cliente vio la orden crearse una vez, aunque internamente

// el servidor pudo haber procesado el request varias veces.Parte 5: Patrón Completo: Event-Driven + REST

Aquí hay un patrón completo que combina todo:

// 1. Evento de dominio

type OrderCreatedEvent struct {

ID string // Event ID para idempotencia

OrderID string

UserID string

Total float64

Timestamp time.Time

}

// 2. HTTP Handler (Adapter Primario)

type OrderHandler struct {

orderService OrderService

eventBus EventBus

idempotencyRepo IdempotencyRepository

}

func (h *OrderHandler) Create(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

idempotencyKey := r.Header.Get("Idempotency-Key")

if idempotencyKey == "" {

http.Error(w, "Idempotency-Key required", 400)

return

}

var req CreateOrderRequest

json.NewDecoder(r.Body).Decode(&req)

// Verificar idempotencia

if cached, err := h.idempotencyRepo.Get(idempotencyKey); err == nil {

w.Header().Set("X-Idempotency-Replayed", "true")

w.WriteHeader(200)

json.NewEncoder(w).Encode(cached)

return

}

// Procesar en transacción

tx := h.db.BeginTx(r.Context(), nil)

defer tx.Rollback()

// Crear orden

order, _ := h.orderService.Create(tx, req)

// Guardar clave idempotencia

h.idempotencyRepo.Save(tx, idempotencyKey, order)

// Publicar evento

h.eventBus.Publish(OrderCreatedEvent{

ID: uuid.New().String(),

OrderID: order.ID,

UserID: req.UserID,

Total: req.Total,

Timestamp: time.Now(),

})

tx.Commit()

w.WriteHeader(201)

json.NewEncoder(w).Encode(order)

}

// 3. Event Subscribers (otros servicios)

type PaymentSubscriber struct {

eventBus EventBus

paymentService PaymentService

}

func (s *PaymentSubscriber) OnOrderCreated(event OrderCreatedEvent) error {

// Retry + idempotencia integrados

return retry.Do(

func() error {

return s.paymentService.Charge(event)

},

retry.Attempts(3),

retry.Delay(1*time.Second),

retry.Multiplier(2),

)

}

// 4. DLQ para fallos

type DLQHandler struct {

db *sql.DB

alertService AlertService

}

func (h *DLQHandler) HandleFailedEvent(event Event, err error) {

h.db.Exec(

`INSERT INTO dead_letter_queue (event_id, event_type, error, created_at)

VALUES ($1, $2, $3, $4)`,

event.ID, event.Type, err.Error(), time.Now(),

)

h.alertService.Alert(fmt.Sprintf("Event %s failed: %v", event.ID, err))

}Conclusión: Decidir Sabiamente

Event-driven architecture no es para todo. Úsala cuando:

✅ Los componentes son realmente independientes

✅ Necesitas desacoplamiento

✅ Escalabilidad es crítica

✅ Puedes tolerar eventual consistency

NO la uses cuando:

❌ Necesitas strong consistency

❌ Hay pocos componentes (overhead no vale la pena)

❌ El flujo es muy complejo (choreography se vuelve un desastre)

❌ Los cambios de estado son críticos (ej: transacciones financieras)

Y cuando la uses:

✅ Entiende si necesitas choreography u orchestration

✅ Implementa retries + DLQ desde el inicio

✅ Usa idempotency keys en REST

✅ Planifica cómo monitoreár eventos fallidos

La diferencia entre event-driven architecture que funciona y que es un desastre está en estos detalles. Hazlos bien desde el inicio.

Tags

Artículos relacionados

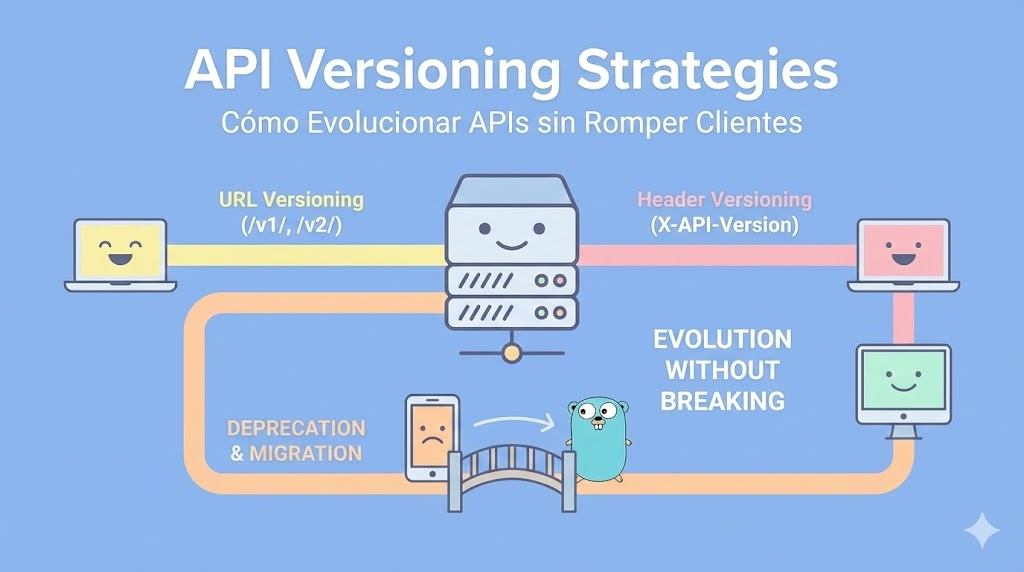

API Versioning Strategies: Cómo Evolucionar APIs sin Romper Clientes

Una guía exhaustiva sobre estrategias de versionado de APIs: URL versioning vs Header versioning, cómo deprecar endpoints sin shock, migration patterns reales, handling de cambios backwards-incompatibles, y decisiones arquitectónicas que importan. Con 50+ ejemplos de código en Go.

Arquitectura de software: Más allá del código

Una guía completa sobre arquitectura de software explicada en lenguaje humano: patrones, organización, estructura y cómo construir sistemas que escalen con tu negocio.

Automatizando tu vida con Go CLI: Guía profesional para crear herramientas de línea de comandos escalables

Una guía exhaustiva y paso a paso sobre cómo crear herramientas CLI escalables con Go 1.25.5: desde lo básico hasta proyectos empresariales complejos con flags, configuración, logging, y ejemplos prácticos para Windows y Linux.